This ASAT feature comes to us from Niall Toner, MA, BCBA of the New York State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook!

I am a special education teacher working with students with autism. At times I find it difficult to figure out what motivates my students and what they’re interested in. Can you make some suggestions about the best way to do this?

This is an excellent question and one that highlights a challenge often experienced not only by teachers but also by family members of individuals with autism. We know that the interests and preferences of individuals with and without autism vary significantly over time. Also, we know that effective teaching of skills and behavior change are predicated upon the timely use of powerful reinforcement (i.e., positive consequences of skilled behavior that motivate and strengthen that behavior). As discussed below, identifying an individual’s preferences is a critical first step in teaching new skills because these preferences often lead to the identification of powerful reinforcers; but how we do this can be easier said than done, especially when the learner has a limited communication repertoire or very individualized interests. The best way to identify preferences is through ongoing preference assessments.

The value of preference assessments

Since many individuals with autism may have difficulty identifying and communicating their preferences directly, we must consider alternative methods of obtaining this information. At the onset, it is important to keep in mind that what may be rewarding or reinforcing for one individual may not be for another. For example, one child may enjoy bubble play, crackers or a particular cause-and-effect toy while a classmate may find one or more of these uninteresting or even unpleasant. Furthermore, an individual’s preferences change across time. For example, an individual may have demonstrated little use for music at age 11, but she may demonstrate a keen interest in music at age 13.

Preference assessments provide a systematic, data-based approach to evaluating a host of potential interests (e.g., food, toys, activities) for an individual. Although preference assessments do require time and effort up front, their use can decrease the time and energy, required to change behavior in the long run. Research indicates that when caregivers use a presumed preference that, in fact, is not the learner’s actual preference, valuable time, energy and resources are lost (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2006).

Types of Preference Assessments

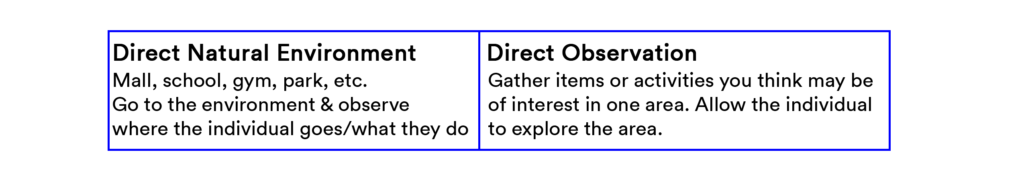

Preference assessment can be conducted in three distinct ways: (1) Interviews and Formal Surveys; (2) Direct observation; and (3) Systematic assessment.

Interviews are a straightforward technique that can be used to gather information quickly. They involve obtaining information from the individual’s parents, siblings, friends, and teachers (and

from the individual, if communicative) by asking both open-ended and comparison questions. Examples of open-ended questions include: “What does he like to do?” “What are his favorite foods?” and “Where does he like to go when he has free time?” Comparison questions might include: “Which does he like better, cookies or crackers?” and “What would he rather do, go for a walk or eat chips?” Resultant information is then compiled in a list and identified items and activities can be piloted out as possible reinforcers.

Formal surveys can also be used to guide these discussions. One widely used survey is the Reinforcement Assessment for Individuals with Severe Disabilities (RAISD; Fisher, Piazza, Bowman, & Amari, 1996). This interview-based survey gathers information about potential reinforcers across a variety of domains (e.g., leisure, food, sounds, smells), and ranks them in order of preference. It should be noted that, although simple and time-efficient, using interviews alone can result in incomplete or inaccurate information. In fact, some studies have shown that, for the same individual, staff interviews did not reveal the same information as using a survey (Parsons & Reid, 1990; Winsor, Piche, & Locke, 1994).

Direct observation involves giving the individual free access to items and/or activities that he or she may like (presumed preferences) and recording the amount of time the individual engages with them. The more time spent with an item or activity, the stronger the presumed preference. In addition, positive affect while engaged with these items and activities could be noted (e.g., smiling, laughing). During these observations, no demands or restrictions are placed on the individual, and the items are never removed. These direct observations can be conducted in an environment enriched with many of the person’s preferred items or in a naturalistic environment such as the person’s classroom or home. Data are recorded over multiple days, and the total time spent on each object or activity will reveal the presumed strongest preferences. Direct observation usually results in more accurate information than interviews but also requires more time and effort.

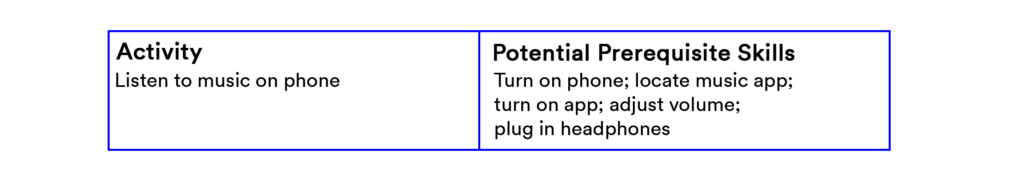

Systematic assessment involves presenting objects and activities to the individual in a preplanned order to reveal a hierarchy or ranking of preferences. This method requires the most effort, but it is the most accurate. There are many different preference assessments methods, all of which fall into one of the following formats: single item, paired items, and multiple items (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2006).

Single item preference assessment (also known as “successive choice”) is the quickest, easiest method. Objects and activities are presented one at a time and each item is presented several times in a random order. After each presentation, data are recorded on duration of engagement with each object or activity.

Paired method or “forced-choice” (Fisher et al., 1992) involves the simultaneous presentation of two items or activities at the same time. All items are paired systematically with every other item in a random order. For each pair of items, the individual is asked to choose one. Since all objects and activities have to be paired together, this method takes significantly longer than the single-item method but will rank in order the strongest to weakest preferences. Researchers found that the paired method was more accurate than the single item method (Pace, Ivancic, Edwards, Iwata & Page, 1985; Paclawskyj & Vollmer, 1995).

The multiple-choice method is an extension of the paired method (DeLeon & Iwata, 1996). Instead of having two items to choose from, there are three or more choices presented at the same time. There are two variations to this method: with and without replacement. In the multiple choice with replacement method, when an object is selected, all other objects are replaced in the next trial. For example, if the individual is given a choice of cookies, crackers, and chips, and he chooses cookies, the cookies will be available for the next trial, but the crackers and chips are replaced with new items. In the without replacement method, the cookies would not be replaced and the choice would only be between the crackers and chips. No new items would be available.

A few final recommendations

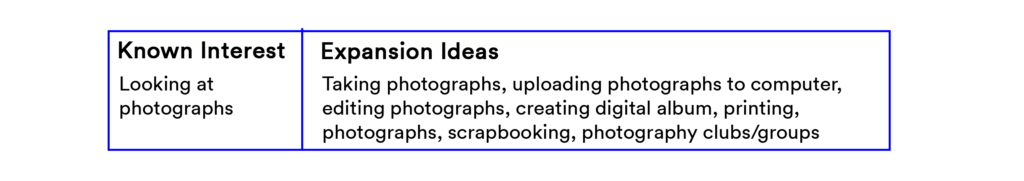

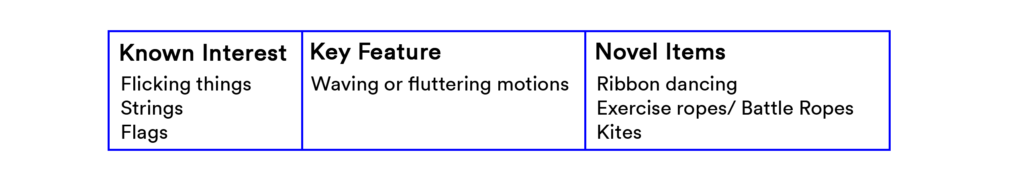

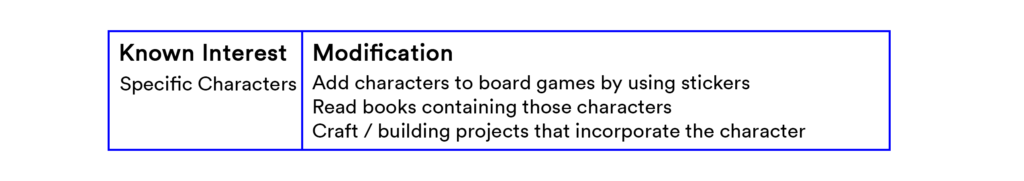

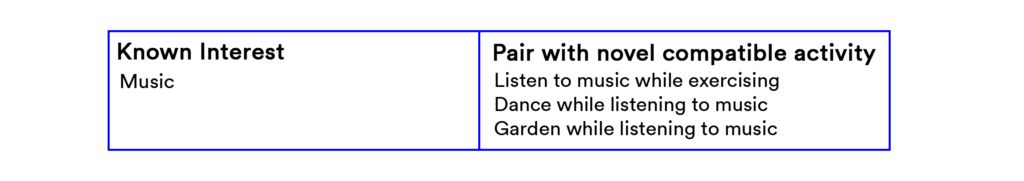

When conducting preference assessments, consider testing leisure items/activities and food assessments separately because food tends to motivate individuals more than toys and other leisure items (Bojak & Carr, 1999; DeLeon, Iwata, & Roscoe, 1997). Also, be sure to assess preferences early and often. Preference assessments should be conducted prior to starting any new intervention or behavior change program. And remember that preferences change over time and require continuous exploration. Therefore, assessments should be updated monthly or whenever an individual appears tired of or bored with the preferred items. Keep in mind too, that the identification of one type of preference may provide ideas for other potential reinforcers. For example, if an individual loves a certain type of crunchy cereal, he/she may like other cereals or crunchy snacks. Or if an individual enjoys coloring with crayons, consider exploring whether he/she may enjoy coloring with markers or using finger paints.

Finally, when selecting a preference assessment method, a practitioner or parent should consider the individual’s communication level, the amount of time available for the assessment, and the types of preferred items that will be available. Taken together, these preference assessment methods can provide the valuable information necessary to help motivate and promote behavior change in individuals with autism.

References

Bojak, S. L., & Carr, J. E. (1999). On the displacement of leisure items by food during multiple stimulus preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32, 515-518.

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward W. L. (2006). Applied Behavior Analysis (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

DeLeon, I. G., & Iwata, B. A. (1996). Evaluation of multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29, 519-533.

DeLeon, I. G., Iwata, B. A., & Roscoe, E. M. (1997). Displacement of leisure reinforcers by food during preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30, 475-484.

Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., & Amari, A. (1996). Integrating caregiver report with a systematic choice assessment. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 101, 15-25.

Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., Hagopian, L. P., Owens, J. C., & Slevin, I. (1992). A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe to profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 491-498.

Pace, G. M., Ivancic, M. T., Edwards, G. L., Iwata, B. A., & Page, T. J. (1985). Assessment of stimulus preference and reinforcer value with profoundly retarded individuals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18, 249-255.

Paclawskyj, T. R., & Vollmer, T. R. (1995). Reinforcer assessment for children with developmental disabilities and visual impairments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28, 219-224.

Parsons, M. B., & Reid, D. H. (1990). Assessing food preferences among persons with profound mental retardation: Providing opportunities to make choices. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23, 183-195.

Windsor, J., Piche, L. M., & Locke, P. A. (1994). Preference testing: A comparison of two presentation methods. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 15, 439-455.

About The Author

Niall Toner MA, BCBA, LBA is a licensed behavior analyst and board certified behavior analyst with over 10 years experience working in the fields of applied behavior analysis and developmental disabilities. Niall is currently the Clinical Director for Lifestyles for the Disabled. Prior to the position he served as a consultant to various organizations including the New York City Department of Education. He also held the position of Assistant Director at the Eden II Programs. Niall has presented locally, nationally and internationally. His interests are Preference Assessments and Functional Analysis, which he presents and publishes.

Originally reposted to Different Roads to Learning on September 28, 2017