Following our last feature on guided playdates, we’ve partnered with the Association for Science in Autism Treatment (ASAT) again this week to bring you an article by Tracie Lindblad, Reg. CASLPO (SLP), MS, MEd, BCBA, on increasing speech intelligibility in children with autism. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook!

How do you increase speech intelligibility (articulation skills) or the variability in the sounds produced by children with autism spectrum disorders?

Answered by Tracie L. Lindblad, Reg. CASLPO (SLP), MS, MEd, BCBA

Approximately 30–50% of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) remain minimally verbal throughout their lives, with little or no functional speech (National Institutes of Health & National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, 2010; Johnson, 2004; Mirenda, 2003). These individuals may rely on more effortful modes of communication such as reaching for desired items, taking another’s hand to gain access, or obtaining the item independent of communication. Attempts to communicate may also take the form of challenging behaviours such as aggression, self-injury, and tantrums.

Approximately 30–50% of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) remain minimally verbal throughout their lives, with little or no functional speech (National Institutes of Health & National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, 2010; Johnson, 2004; Mirenda, 2003). These individuals may rely on more effortful modes of communication such as reaching for desired items, taking another’s hand to gain access, or obtaining the item independent of communication. Attempts to communicate may also take the form of challenging behaviours such as aggression, self-injury, and tantrums.

Parents face a difficult task in choosing a treatment for minimally verbal children with ASD because a wide range of techniques are routinely used by speech-language pathologists and behaviour analysts with varying degrees of success and evidence.

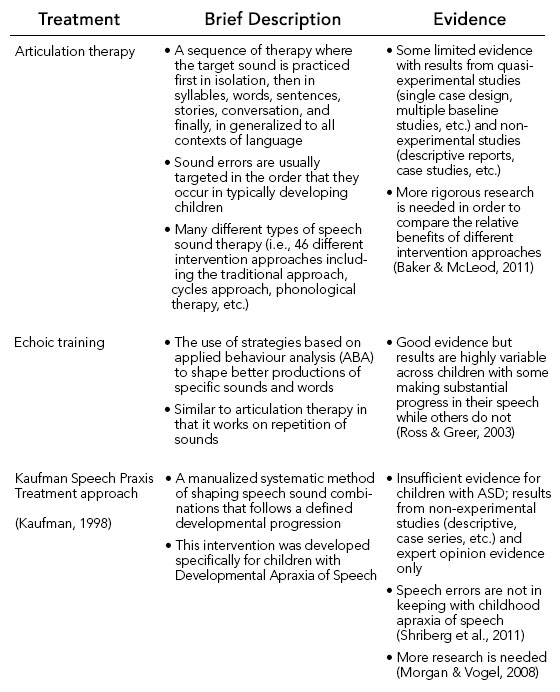

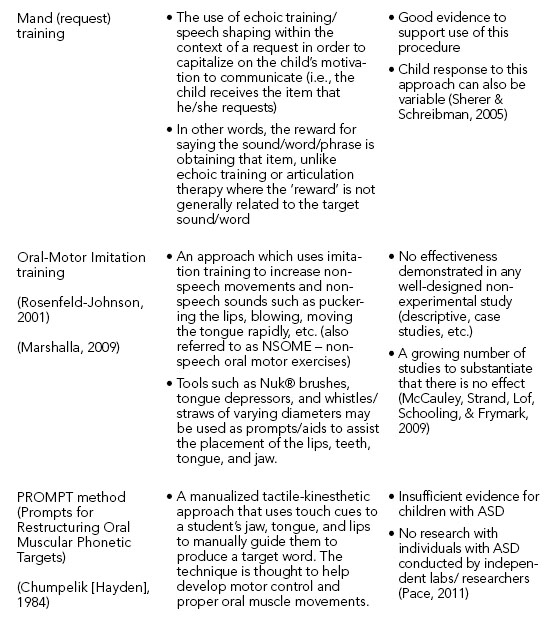

The following table highlights some of the most-commonly implemented interventions to target speech skills and the current evidence base for each.

Within the fields of behaviour analysis and speech pathology, evidence-based practice (EBP) should shape and guide our treatment decisions. EBP is the integration of:

- external scientific evidence,

- clinical expertise/expert opinion, and

- client/patient/caregiver perspectives.

Principles of EBP can help any professional to provide high-quality services which reflect the interests, values, needs, and choices of the individuals, and promote the best outcomes possible with the current evidence to date.

Therefore, treatment decisions should take into account a number of factors such as:

- current level of evidence

- learner characteristics such as initial echoic repertoire

- motivation of the child

- response to imitation-type programs

- training and background of the professional/team (e.g., early intensive behaviour intervention (EIBI) team, SLP, paraprofessional, etc.)

- intensity of the planned intervention

Working as a collaborative team comprised of behaviour analysts, early interventionists, and speech-language pathologists will allow development of appropriate targets while drawing on the specific strengths from each profession. Speech-pathologists are trained in the developmental acquisition of speech sounds and in the selection of appropriate substitutions or simplification of speech sounds in order to help the student progress from easier targets to more difficult ones. On the other hand, behaviour analysts are uniquely trained in using shaping procedures effectively, assessing motivation to assist in learning, and in the collection of detailed and specific data to guide treatment decisions. As part of a collaborative team, the child benefits from a well designed program with appropriate targets.

When guided by the current evidence for treatment and the clinical expertise/knowledge from the fields of ABA and speech pathology, the following sequence may be helpful in designing a program to target echoic/speech production skills:

- Conduct an initial assessment of the child’s sound productions. This may be completed by an SLP using standard articulation or phonological tests or by a behaviour analyst using assessment tools such as the ABLLS-R (Partington, 2008) or VB-MAPP (Sundberg, 2008), which includes the Early Echoic Skills Assessment (EESA) (Esch, 2008).

- Compile a list of items / words that the child would typically be motivated to request on a daily basis. Determine appropriate word approximations or the shaping steps for each of the words.

- Set up opportunities throughout the day for the child to request the items/actions/activities that he/she likes in order to practice the target sounds/words. Some of these opportunities may be already occurring; however, it is often necessary for additional opportunities to be created and to ensure that the request is reinforced when it occurs.

- Record the frequency and accuracy of the child’s production in order to determine when a higher/more complex target will be required (i.e., shape the sound/word to a more ‘typical’ production).

- Prompts or cues may be added to the practice trials to help the student in meeting the targeted production. These prompts will need to be systematically faded so that the student produces the sound/word independently with the same accuracy.

- Difficult targets should also be practiced within the context of an echoic program where the child is given additional opportunities for practice. Systematic, frequent teaching, prompting and reinforcement are key in changing the behavior.

- A planned effort to promote the generalization of all targets outside of the structured sessions is critically important.

- Continue to assess the intelligibility of the child (to an unfamiliar listener) in order to ensure that vocal speech is functional in terms of a communication system. If the child is not understood 80% of the time or better to an unfamiliar listener, then an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) system, such as Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS, Bondy & Frost, 2001), should be considered for communication while speech skills continue to develop.

REFERENCES

Baker, E., & McLeod, S. (2011, April). Evidence-Based Practice for Children with Speech Sound Disorders: Part 1 Narrative Review. Language, Speech, Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 102-139.

Bondy, A., & Frost, L. (2001). The Picture Exchange Communication System. Behavior Modification, 25(5), 725-744.

Chumpelik (Hayden), D. A. (1984). The PROMPT System of Therapy: Theoretical framework and applications for developmental apraxia of speech. Seminars in Speech and Language, 5, 139-156.

Esch, B. (2008). Early Echoic Skills Assessment. VB-MAPP Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program. Mark Sundberg.

National Institutes of Health & National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (April 13-14, 2010). NIH Workshop on Nonverbal School-Aged Children with Autism. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/funding/programs/10autism/pages/detail.aspx

Johnson, C. P. (2004). Early clinical characteristics of children with autism. In V. B. Gupta, Autistic spectrum disorders in children (pp. 96-134). New York: Marcel Dekker.

Kaufman, N. (1998). Kaufman speech praxis treatment kit for children. Gaylord, MI: Northern Speech Services.

Marshalla, P. (2009). Improving Intelligibility in Apraxia and Dysarthria. Mill Creek: Marshalla Speech and Language.

McCauley, R. J., Strand, E., Lof, G. L., Schooling, T., & Frymark, T. (2009). Evidence-Based Systematic Review: Effects of Nonspeech Oral Motor Exercises on Speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 343-360.

Mirenda, P. (2003). Toward functional augmentative and alternative communication for students wtih autism: Manual signs, graphic symbols, and voice output communication aids. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 34, 203-216.

Morgan, A. T., & Vogel, A. P. (2008). Intervention for Childhood Apraxia of Speech. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006278.pub2

Pace, J. (2011). Critical Review:Is PROMPT an effective treatment method for children with speech production disorders? Retrieved July 23, 2012, from University of Western Ontario, School of Communication Sciences and Disorders, CSD 9761 Evidence Based Practice for Clinicians: https://www.uwo.ca/fhs/csd/ebp/2010_11.html

Partington, J. (2008). Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills (revised). Behavior Analysts Inc.

Rosenfeld-Johnson, S. (2001). Oral-Motor exercises for speech clarity. Tucson, Arizona: Innovative Therapists International.

Ross, D. E., & Greer, R. D. (2003). Generalized imitation and the mand: introducing first instances of speech in young children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 24, 58-74.

Sherer, M. R., & Schreibman, L. (2005). Individual Behavioral Profiles and Predictors of Treatment Effectiveness for Children with Autism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 525-538.

Shriberg, L. D., Paul, R., Black, L. M., & van Santen, J. P. (2011). The hypothesis of apraxia of speech in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(4), 405-426.

Sundberg, M. (2008). VB-MAPP: Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program A Language and Social Skills Assessment Program for Children with Autism Or Other Developmental Disabilities: Guide. Mark Sundberg.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tracie Lindblad, SLP, Reg. CASLPO, MSc, MEd, BCBA is a Speech-Language Pathologist and Board Certified Behaviour Analyst (BCBA) with 30 years experience working with children and youth with developmental disabilities. She has degrees in Psychology, Education, and Speech-Language Pathology and is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst.Tracie is the Clinical Director of a private interdisciplinary centre, Monarch House, which is located in Oakville, ON and is part of the CBI Health Group which is a large national private healthcare provider in Canada.

Tracie has presented workshops and training sessions to numerous school boards, agencies, and organizations throughout Canada, the United States, and most recently in Europe on a variety of topics related to the fields of speech-language pathology (i.e., communication development, delays, and disorders), Autism Spectrum Disorders, Alternative and Augmentative Communication (e.g., low- and high-tech AAC, speech generating devices, etc.), and ABA.

Tracie has also served as a research investigator on a number of projects within the field of ASD, ABA, and developmental disabilities in partnership with various agencies and universities. Tracie is also involved in clinical research investigations conducted at Monarch House under the direction and collaboration with Dr. John Rapp (Auburn University), Drs. John and Barb Esch (Esch Consultants, Kalamazoo, MI) and Dr. Marc J. Lanovaz (Université de Montréal).

Tracie also serves on a number of agency Boards and associations. She is currently the Co-Chair for the Speech Pathology and Applied Behaviour Analysis SIG which is a Special Interest Group affiliated with the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) and is also co-chair of the Public Relations committee for ASAT – the Association for Science in Autism Treatment. Tracie also continues to serve on the Board of Directors for New Leaf: Living and Learning Together Inc., a non-profit agency that provides residential services to adults with dual diagnosis.

ABOUT the Association for Science inAutism Treatment

We promote safe, effective, science-based treatments for people with autism by disseminating accurate, timely, and scientifically sound information; advocating for the use of scientific methods to guide treatment; and combating unsubstantiated, inaccurate and false information about autism and its treatment. Since autism was first identified, there has been a long history of failed treatment fads, levied on vulnerable individuals and their families. Many of these treatments have been too hastily adopted by professionals, sensationalized by the media, and embraced by consumers before evidence existed for their effectiveness or safety. Visit our website at www.asatonline.org and subscribe to our free quarterly newsletter at www.asatonline.org/newsletter/. Follow us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/ASATonline and on Twitter at @asatonline.