This month’s ASAT feature comes to us from Alice Walkup, MS, BCBA. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook! You can read more of our ASAT featured posts here.

How does a behavior consultant who is invested in the child’s best outcome encourage parents to actively participate in home-based intervention?

Answered by Alice Walkup, MS, BCBA

For many parents of children with autism, participation in a home-based behavioral intervention program may seem overwhelming. In addition to managing and advocating for the child’s various services, parents may find it difficult to attend to the needs of other family members, their spouses, and their jobs. Participating in their child’s home-based program can certainly seem like one more responsibility for which there simply is not enough time. It is important to appreciate that other commonly-endorsed autism therapies, such as occupational or speech therapy, do not usually require the same level of time, energy and parental involvement that an intensive behavioral intervention program does.

Understanding And Assessing Barriers To Participation

When you conduct the intake interview (and likely throughout the consultative relationship), it is important to take note of any potential barriers to the parents’ participation. Education level, socio-economic status, competing responsibilities, other family members in the home, cultural beliefs, and beliefs about autism and autism treatments are just a few factors to consider. It is also important to keep in mind that parents may be unaware that the skills of children with autism (e.g., communication, compliance) do not automatically generalize from therapists to parents. As such, it is important for consultants to gauge the willingness and motivation of family members to be active participants in their child’s intervention program (Taylor & Fisher, 2010).

From the outset, it is important to explain to parents that they will be a critical part of their child’s learning and will be shown how they can help the child practice what they’ve been taught during therapy sessions. Parents may also hold misconceptions regarding behavioral intervention, such as a belief that behavioral techniques are based exclusively on punishment. Explaining the intervention process at the outset will help eliminate such concerns. A final point to consider is that many parents of children with autism experience their own psychological challenges, such as depression and anxiety. Some research suggests that mothers with depressive characteristics do not acquire as much information and skills during parent training as mothers without depressive characteristics (Gelfand, Teti, Seiner, & Jameson, 1996; Cicchett, Rogosch, & Toth, 2000). Such issues may present challenges for consultants but once identified can be taken into consideration when individualizing consultation and the scope of the home-based intervention. It may also become clear during the intake process that referral to other services or resources are warranted.

Setting The Stage For Success

When working with a new family, there are many strategies you can employ to build a collaborative, open relationship from the outset. These include:

- asking questions that will help you better understand the parents’ experiences as they relate to supporting their child with autism. Such questions may include asking what other services/therapies the child has received (or is still receiving), what supports (community, family and individual) are available to the parents, and what they see as their biggest challenges related to parenting a child with autism

- being an attentive and compassionate listener

- minimizing “behaviorspeak,” including clinical terms and acronyms with which the parent is unfamiliar. When explaining behavioral principles, it may help to use simpler, every-day examples to illustrate the concepts

- explaining the intervention process and what a typical session may look like

- using language that fosters a cooperative spirit; for example, saying, “we as a team” instead of “you” when discussing the home-based intervention

Goal Selection

When meeting with parents for the first time, encourage them to identify the hopes and fears they have for their child as doing so will help guide intervention planning and goals. It is equally important to identify goals that are most relevant to the family such as eating, sleeping, and community-based goals (Taylor & Fisher, 2010). This conversation should address both short- and long-term goals for the child, such as playing with friends, sitting appropriately in church, or attending college. With this knowledge, the consultant can assist parents in identifying their top three most important goals. One strategy for longer-term goals is to give each a name, such as “Project Friendship” for a socialization goal, as it will serve as a reminder to focus on the big picture. Once these are identified, the shorter-term goals and associated skills to be taught can be more easily defined, and the parents can see how they are supporting the longer-term goal. After selecting initial teaching targets and determining appropriate instructional strategies, the behavioral team will begin implementation. Keep in mind that some parents may challenge your typical approaches to behavior change, such as finding it difficult to tolerate extinction bursts, appreciating the need for direct teaching of desired skills, or using edible reinforcers. This again highlights the critical importance of discussing the intervention process and teaching strategies with parents at the outset. You can also explain their potential roles as teachers and that they will be included in their child’s teaching at the appropriate time. Doing so will help foster a more collaborative relationship and help parents better anticipate and understand their roles in the behavioral intervention process.

Promoting Enduring Participation

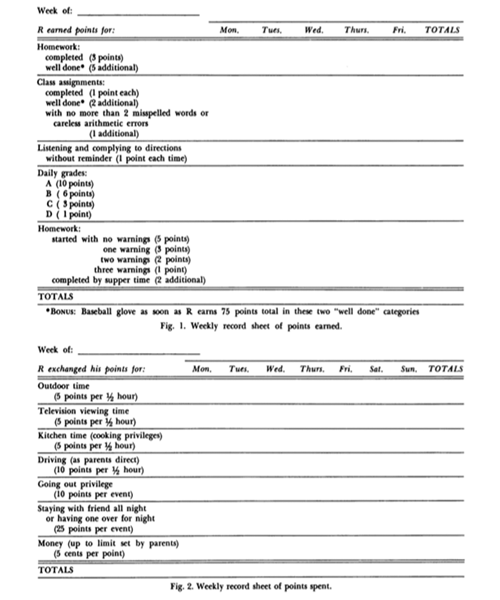

Once parents agree to be involved in their child’s home-based intervention, many factors can potentially influence their adherence to behavioral programs and their participation. Continued parent participation can be impacted by parental perceptions of themselves as effective in behavior change, confidence in the treatment approach, and by the degree to which the child is accepted in the family and community, among other variables (Moore & Symons, 2011). When engaging parents in the teaching process, the key is setting them up to be successful. Start with a smaller goal that the child has already mastered with the in-home therapists so that parents leave the teaching interaction feeling effective in promoting behavior change in their child. Utilizing best practices for training that incorporate modeling, rehearsal, and feedback will provide parents with valuable opportunities to both observe and practice teaching the targeted skill to their child. Tracking and graphing their progress in addition to the child’s, then taking the time to review it with them regularly, is a good strategy to provide encouragement throughout the intervention process.

Parents and consultants should also consider whether or not the funding source for child’s in-home services requires parent participation (and to what degree). Currently, some funding sources place a significant emphasis on training the parents to be effective at-home therapists and require behavior consultants to teach parents therapeutic skills to a level of mastery that they can do so. Parents can be asked to implement programs and collect data, and the consultant must report the level of parent involvement to the funding source. In extreme cases, in-home services have actually been terminated due to a lack of parent participation. While it is often more effective to appeal to parents on a more personal level when encouraging their involvement, this requirement and the potential loss of services should be discussed.

Behavior consultants providing in-home services are tasked with addressing a child’s needs within an existing, and sometimes challenging, family dynamic. The ideal in-home behavioral intervention program would include extensive and high-quality parent participation during therapy sessions; however, this may not always be possible. As such, we must individualize the type and extent of parent involvement on a case-by-case basis and employ our skills as consultants to encourage and maintain active parent participation, where possible. Despite the challenges that may accompany our efforts, it’s important to remember that, at the end of the day, we are all working towards the same goal: ensuring the best possible outcomes for the child.

References

Cicchetti, D., Rogosch, F. A., & Toth, S. L. (2000). The efficacy of toddler–parent psychotherapy for fostering cognitive development of offspring in depressed mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 135-148.

Gelfand, D. M., Teti, D. M., Seiner, S. A., & Jameson, P. B. (1996). Helping mothers fight depression: evaluation of a home-based intervention program for depressed mothers and their infants. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 406-422.

Moore, T. R., & Symons, F. J. (2011). Adherence to treatment in a behavioral intervention curriculum for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Modification, 35, 570-594.

Taylor, B. A., & Fisher, J. (2010). Three important things to consider when starting intervention for a child diagnosed with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 3, 52-53.

Citation for this article:

Walkup, A. (2012). How does a behavior consultant who is invested in the child’s best outcome encourage parents to actively participate in home-based intervention? Science in Autism Treatment, 9(4), 4-6.

About The Author

Alice M Walkup, MS, BCBA currently resides in Los Angeles, CA where she practices behavior analysis with clinical populations.