This month’s ASAT feature comes to us from Mary Jane Weiss, Ph.D., BCBA-D,LABA and Nicole Pearson, BCBA-D. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook!

I am a mother of three children, one of whom has autism and requires a tremendous amount of time and care. I worry about how this is impacting my other children, both of whom are a few years older and are very aware of how our family has changed as a result of their sibling’s diagnosis. Do you have any advice on how to best address this with them?

Answered by: Mary Jane Weiss, Ph.D., BCBA-D,LABA

Professor of Education and Director of Programs in Autism and Applied Behavior Analysis, Endicott College and

Nicole Pearson, BCBA-D

Founder, West Side Behavioral Associates

Having a child with autism spectrum disorder inevitably impacts the entire family. From the stress and anxiety that accompanies the initial diagnosis to the time-intensive nature of navigating treatment options and providers, raising a child with autism presents unique challenges for parents. It can also present challenges for siblings as the sibling relationship is inevitably different from that of typical siblings. And while many of these differences can be positive and rewarding, it’s important for parents to be aware of the needs of siblings so that they can provide meaningful guidance and support.

While children of younger ages may not be fully aware of their sibling’s disability, they likely detect parental stress, perceive inequities in the amount of time and attention given and struggle with a sense of disruption in overall family life (Feiges & Weiss, 2004; Smith & Elder, 2010). As children age and their awareness grows, siblings may experience adjustment difficulties. These difficulties are influenced by such factors as sibling age and gender as well as family size. Siblings closer in age to the child with autism, and those who are younger and have not yet developed effective coping strategies can be more affected. However, as a parent, there are many strategies you can take to support sibling coping and adjustment.

Foster a supportive environment at home: Siblings are often aware of how different their experiences are from that of others, especially their friends. As a result, they may feel many emotions, including fear, anger, embarrassment, resentment and guilt, among others. Encouraging an environment of open communication allows the sibling to safely express negative emotions and frustrations. Listen to and reassure your child that it’s okay to have these feelings, and offer suggestions on how to work through them together. Doing so also helps with positive coping and establishes a foundation for good familial communication and problem solving.

Further, as siblings become aware of such differences, they will likely look to their parents and family members for guidance. Thus, parent coping and adjustment play an important role in sibling adjustment. As such, it is important for parents to be cognizant of the impact their actions, behaviors and decisions will have on all of their children.

Ensure your child understands what autism is: Parents sometimes overestimate their typical child’s understanding of autism as the child may be able to explain what it is without fully comprehending it. They may also pick up on information they overhear but likely have more questions than answers. Making sure that siblings have developmentally-appropriate information will help reduce their fears and misconceptions (Glasberg, 2000; Harris & Glasberg, 2003). These explanations can go a long way in influencing how siblings view and interact with their sibling with autism and how well they are able to explain autism to their peers.

When speaking with children under age nine, parents should keep explanations brief and frame the sibling with autism’s deficits in the context of having not yet learned or mastered particular skills, such as playing with others or communicating in ways that other children do. For example, saying, “Your sister learns a bit differently than you and me, so she needs extra help” or “Your brother may not be able to talk but we are teaching him other ways to show us what he wants to say.”

As children age, explanations can be more involved, such as sharing that autism is a problem in the brain and that it presents differently in each child. Depending on the extent of the child with autism’s behavioral problems, it may be necessary to help the sibling understand why they’re occurring and their role in behavioral escalations. Such escalations can be scary, embarrassing and disruptive for typical siblings so providing them with clear explanations can help alleviate some of these feelings. Regardless of the children’s age, parents should offer reassurance (especially of safety) to typical siblings, and convey love and acceptance of everyone in the family.

From a timing perspective, starting to discuss autism with siblings at an early age can be helpful, especially before they begin school or start having friends over. That way, they can be prepared with information about how to explain what may appear to be usual or different behavior in their sibling with autism. There are several free online resource guides available:

• Autism Speaks offers a “Siblings Guide to Autism” toolkit designed for siblings ages 6-12 that parents and siblings can read together to learn more about autism and facilitate conversation about it

• Organization for Autism Research’s “Kit for Kids” offers an illustrated booklet for elementary and middle school students, called “What’s up with Nick?” and “Autism, my sibling, and me”

Promote meaningful relationships between siblings: While every sibling relationship is special, the communication and socialization deficits inherent in autism diagnoses can make sibling bonding more difficult. Creating opportunities for younger children to play together or helping older siblings to find common interests, even if it’s as simple as doing a puzzle together or playing a video game, can go a long way in increasing the quality and quantity of interactions and ultimately building sibling bonds.

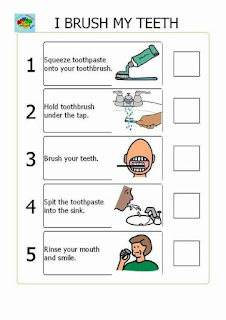

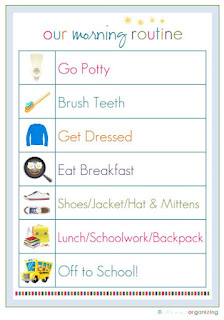

Another way to foster meaningful relationships between siblings is to teach your typical children how to be mentors to their younger sibling with autism. Doing so can be very fulfilling for siblings and promote feelings of self-efficacy and nurturing. It also creates opportunities for siblings to engage with one another socially and have positive interactions with their sibling with autism. Prior to starting, make sure that your typical children understand their sibling with autism’s skills, preferences and interests and start with easy tasks to ensure success. Such tasks might include modeling how your typical siblings can engage in simple toy play or teach their sibling with autism a basic daily living skill like putting on a coat or how to wash hands. Other skills that can be useful to teach include:

• how to get your sibling with autism’s attention,

• how to provide praise and reinforcement when he does well,

• how to assist him when he cannot do something,

• how to help him stop playing and clean up.

Build in one-on-one time for each sibling and foster individuality: Siblings are inevitably affected by the inordinate amount of time, energy and resources that are spent caring for their sibling with autism. Further, activities common in typical family life such as all spending time together, going to a movie or on vacation may be more limited. While inequities exist in all families, they are intensified in a family who has a child with autism. And if typical siblings feel dissatisfied with these inequities, their relationship with their sibling with autism is negatively impacted (Rivers & Stoneman, 2008). To help minimize the impact of these inequities, it’s important to make time for one-on-one interaction with each sibling. While this can seem difficult in the throes of managing busy schedules and the demands of therapies, carving out even a small amount of time where you’re giving your child your undivided attention can go a long way. So whether its running errands together or going for pizza, make time to check-in with your other children and let them know that even though they may not always get as much attention as their sibling, they’re loved and cared for equally.

And while having a child with autism is a 24/7 commitment, helping to foster distinct roles and interests in each child can further reduce the stress that siblings may feel. Encourage siblings to get involved in sports, clubs or other community activities where they can develop relationships with peers and just have fun. Doing so allows them the time and space to be their own person and establish a sense of individuality not defined by their sibling with autism (OAR, 2014). Ultimately, it may also make siblings more available to enjoy spending time with their sibling with autism.

Consider additional sources of support: Finally, sibling groups can be a helpful source of support. They provide siblings the chance to meet and speak with others who are going through similar experiences and can give them accurate and age-appropriate information about autism. Often these groups can help reduce fear and misconceptions among siblings as well as the feelings of isolation many experience. If a support group isn’t readily available within your children’s school or your community, consider looking at some of the following resources for more information:

• Sibling Support Project – offers more than 475 community support programs, called SibShops, for younger siblings of children with special needs.

• Online resources: There are several online communities for siblings, both teens and adults:

o SibTeen, an online Facebook group for teen siblings: https://www.siblingsupport.org/connect-with-others-sibs/meeting_other_sibs_online/sibteen

o SibNet online forum for adults: https://www.siblingsupport.org/connect-with-others-sibs/meeting_other_sibs_online/sibnet

The Organization for Autism Research (OAR) has also developed the “Autism Sibling Support Initiative” offering helpful resource guides for young children, teens and parents.

While much is often said about the challenges faced by siblings of people with autism, there are also substantial positive outcomes. Most siblings who reflect on the experience in adulthood attribute their high levels of compassion, tolerance, patience, and concern for others to having had a sibling with special needs. Furthermore, many of them develop a sense of mission and enter helping professions.

There is no universal description of the ways in which this role changes the lives of siblings of children with autism. And every sibling pair is on their own unique journey. But while this is a role that is not chosen by the sibling, it is a role that most siblings truly embrace. Parents can help their typically developing children by creating an environment of transparency and openness about autism and about issues arising in the family associated with it. They can help siblings find effective ways to interact with their brother or sister with autism, and can foster mentorship roles for them with their sibling. Parents can also ensure that every child in the family gets needed attention and permission to pursue their own dreams. Finally, they can remember that most siblings of children with autism end up being compassionate human beings who treasure their sibling and who note both the struggles and the strength that the family experienced as a result of being touched by autism.

Note: This submission was adapted from Drs. Weiss and Pearson’s book chapter, “Working effectively with families of children with autism spectrum disorders: understanding family experience and teaching skills that make a difference” which appeared in “School success for kids with autism.”

References:

Feiges, L.S., & Weiss, M.J. (2004). Sibling stories: Growing up with a brother or sister on the autism spectrum. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing Company

Glasberg, B.A. (2000). The development of siblings’ understanding of autism and related disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 143-156.

Harris, S.L., & Glasberg, B.A. (2003). Siblings of children with autism. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

Organization for Autism Research (OAR). (2014). Brothers, sisters and autism: A parent’s guide to supporting siblings. Retrieved from: http://www.researchautism.org/family/familysupport/documents/OAR_SiblingResource_Parents_2015.pdf

Rivers, J. W., & Stoneman, Z. (2008). Child temperaments, differential parenting, and the sibling relationships of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1740-1750.

Smith, L. O., & Elder, J. H. (2010). Siblings and family environments of persons with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Nursing, 23, 189-195.

Weiss, M. J., & Pearson, N. K. (2012). Working effectively with families of children with autism spectrum disorders: Understanding family experience and teaching skills that make a difference. A. L. Egel, K. C. Holman, & C. H. Barthold (Eds.). School success for kids with autism. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Please use the following format to cite this article:

Weiss, M. J. (2016). Clinical Corner: How to Manage the Impact of Child With a Disability on Siblings. Science in Autism Treatment, 13(2), 22-26.

Mary Jane Weiss, Ph.D., BCBA-D, LABA is a Professor at Endicott College, where she directs the Master’s Program in ABA and Autism and is a mentoring faculty member in the Doctoral program. She also does research at Melmark. Dr. Weiss has worked in the field of ABA and Autism for over 30 years. She received her Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from Rutgers University in 1990 and she became a Board Certified Behavior Analyst in 2000. She previously worked for 16 years at the Douglass Developmental Disabilities Center at Rutgers University, where she served as Director of Research and Training and as Clinical Director. Her clinical and research interests center on defining best practice ABA techniques, exploring ways to enhance the ethical conduct of practitioners, evaluating the impact of ABA in learners with autism, teaching social skills to learners with autism, training staff to be optimally effective at instruction, and maximizing family members’ expertise and adaptation. She serves on the Scientific Council of the Organization for Autism Research, is on the Professional Advisory Board of Autism New Jersey, is a regular reviewer for a variety of professional journals, and is a frequent member of service committees for the Behavior Analyst Certification Board. She is also a Past President of the Autism Special Interest Group of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, a former member of the Board of the Association for Professional Behavior Analysts, and a former Vice President of the Board of Trustees for Autism New Jersey.

Dr. Nicole Pearson is a licensed psychologist and Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA-D) who has specialized in working with individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities for almost a decade. Dr. Pearson received her initial training in Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) at the Alpine Learning Group and went on to work in a number of other public and private educational settings, including NYC Autism Charter School where she served as Director of Education. She has also worked with autism programs internationally in Kenya and the Maldives. Most recently, Dr. Pearson served as a Behavioral Psychologist at St. Mary’s Hospital for Children, working with children with complex medical needs and training clinical staff in treatment protocols. She holds Masters and Doctoral degrees in Psychology from Fairleigh Dickinson University and a BS in Business Administration from Villanova University.