“Dear Behavior BFF, bedtime is the absolute worst time of day. I dread putting my kids to bed because they draw everything out with so much drama! They argue, complain, cry, you name it! Why is it so hard? Can you help us?”

Unfortunately, you are not alone in this one. Bedtime can be hard for so many kids and parents (me included!).

We could spend all day guessing why our kiddos fight going to bed. Do they have FOMO (fear of missing out) on what parents do after they go to bed? Are they not tired enough? Are they too tired? Are their pajamas truly itchy? Is there really a scary shadow of a monster on the wall? But those questions don’t guide us to a solution to deal with this daily problem.

Instead- let’s look at it from a solution-based perspective. What would a solution look like for you? What behaviors are you looking to increase at bedtime?

Sample target behaviors (the things you are trying to get your kids to do MORE of):

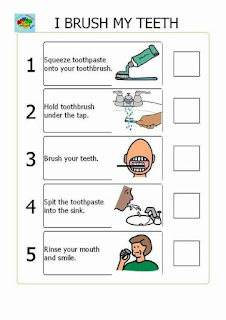

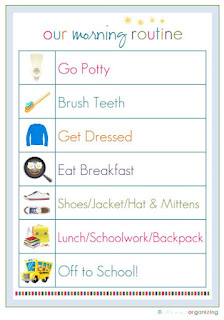

- Finish pre-bed routines with minimal reminders

- Follow directions with 1 or 2 reminders

- Use a quiet voice

- Only come out of your room 1 time after bedtime

- Ask nicely for things

- Read or play quietly if you aren’t ready to go to sleep

So what can we do to increase these behaviors in our homes each evening? Try some evidence-based positive reinforcement strategies!

Premack principle: FIRST (do the unpreferred task), THEN (get a reinforcer).

The FIRST needs to be clear and direct. Tell your child what the target behavior is. What CAN they do right now to earn reinforcement? The THEN needs to be worth it for your child. Choose a quality reinforcer or better yet- let your kiddo(s) choose!

- FIRST use a quiet voice at bedtime, THEN we can sing a song together.

- FIRST stay in your room until 7am, THEN you can watch a TV show in the morning.

- FIRST follow directions at bedtime, THEN choose a toy to take to bed with you.

Token Economy: A structured reinforcement system where your child earns tokens (stickers, marbles, points) to exchange for a big reinforcer when enough have been earned. Steps to using a token economy to make bedtime easier may include the following:

- Choose specific target behaviors. Tell your child 1-3 things they CAN and should do at bedtime instead of problem behavior.

- Give the token (sticker on a sticker chart, marble in a marble jar, points on a point sheet, etc) every time your child does these desired bedtime behaviors.

- When they reach their goal- let them use their tokens to ‘buy’ the big reinforcer!

To be successful, be consistent. Give a token every time your kiddo does one of the desired behaviors. Be clear- make sure your children know what the desired behaviors are. Don’t set the goal too high to start with. Help your children to be successful to get them on board with the plan!

No matter what evidence-based strategy you choose, be consistent with it. Give reinforcement as immediately as possible. Catch your children being good and give high-quality reinforcers!

References

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis.

Homme, L. E., Debaca, P. C., Devine, J. V., Steinhorst, R., & Rickert, E. J. (1963). Use of the Premack principle in controlling the behavior of nursery school children. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior.

Kazdin, A. E. (1982). The token economy: A decade later. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 15(3), 431-445.

Kazdin, A. E. (Ed.). (1977). The token economy: A review and evaluation. Plenum Publishing Corporation.

Knapp, T. J. (1976). The Premack principle in human experimental and applied settings. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 14(2), 133-147.

This piece originally appeared on www.bSci21.com.

About The Author

Leanne Page, MEd, BCBA, is the author of Parenting with Science: Behavior Analysis Saves Mom’s Sanity. As a Behavior Analyst and a mom of two little girls, she wanted to share behavior analysis with a population who could really use it- parents!

Leanne’s writing can be found in Parenting with Science and Parenting with ABA as well as a few other sites. She is a monthly contributor to bSci21.com , guest host for the Dr. Kim Live show, and has contributed to other websites as well.

Leanne has worked with children with disabilities for over 10 years. She earned both her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from Texas A&M University. She also completed ABA coursework through the University of North Texas before earning her BCBA certification in 2011. Leanne has worked as a special educator of both elementary and high school self-contained, inclusion, general education, and resource settings.

Leanne also has managed a center providing ABA services to children in 1:1 and small group settings. She has extensive experience in school and teacher training, therapist training, parent training, and providing direct services to children and families in a center-based or in-home therapy setting.

Leanne is now located in Dallas, Texas and is available for: distance BCBA and BCaBA supervision, parent training, speaking opportunities, and consultation. She can be reached via Facebook or at Lpagebcba@gmail.com.