By: Randy Horowitz, M.S. Ed., S.A.S. and Joanne Capuano Sgambati, Ph.D., BCBA-D, LBA

Sexuality is part of normal human development for every man, woman and child. It is a basic need and an integral part of life. Sexuality is not just physical maturity and sexual intercourse; it is diverse and personal. It’s about relationships, intimacy, and thoughts and feelings about other people. Individuals with ASD follow the same physiological sexual development and interests as their typically developing peers; About 75% of individuals on the spectrum desire and engage in some form of sexual behavior. (A comparable percentage to the neuro-typical population). Behaviors range from masturbation to intercourse and many steps along the way. Individuals with ASD have the same sexual interests, needs, and rights as anyone else, they just may not have the same ways to express themselves and share their feelings.

So what else is unique about individuals with ASD in relation to sex education?

- Poor social competence and limited peer relationships lead to few opportunities to obtain sexual information, have sexual relationships, and fulfill their desire to have a healthy romantic and sexual life.

- Cognitive differences (difficulty with inferencing, perspective taking, and theory of mind) can impact their understanding, generalization, and application of sexual information.

- Language and communication challenges as well as social skills deficits can get in the way of initiating and maintaining relationships.

- Societal barriers which interfere with learning necessary sexual information that can prevent intimate relationships from taking place.

It is a natural instinct for parents and teachers to want to protect their children; however, by avoiding speaking about sexuality and sex education, they may be suggesting that sexuality is unimportant or shameful and they may be leaving their children even more vulnerable to frustration, problematic behaviors, social isolation, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem and even victimization.

So, how can we best educate learners with ASD about sexuality?

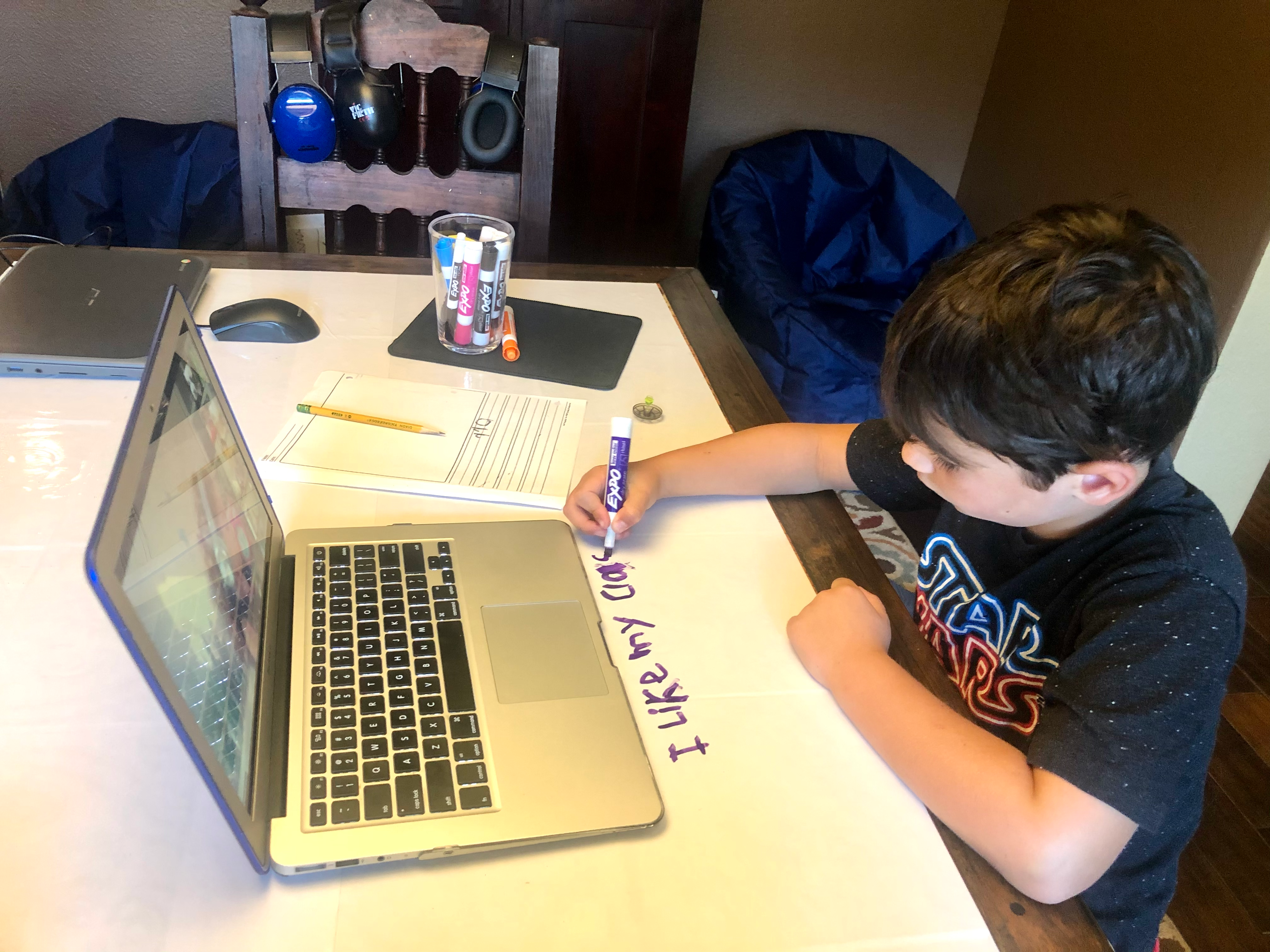

Start early: Children with ASD may have a hard time with change and take longer to learn concepts. Start very early; and present positively in a calm and clear manner:

- Body part ID

- Using appropriate words and language to identify genitals.

- Private vs. public (e.g., places, behaviors, hygiene, and eventually conversations and on-line activities etc.)

Remember what is cute as a child (like hugging teachers), may be inappropriate in middle school. So, teach appropriate social boundaries early on. Do not wait until puberty to discuss body changes as it can be alarming to teens with ASD who resist change (pubic hair, private time for masturbation, shaving, bras, maxi pads, etc.).

Use appropriate teaching strategies: You can teach sexuality skills the same way you teach other skills to those with ASD. Some ideas are use of visuals, schedules, task analysis, functional communication training, and video modeling. Remember that sexual behavior is still behavior and adheres to the laws of applied behavior analysis. If there is a behavior to increase, decrease, or maintain it is important to know the function of that behavior in order to modify it.

Remember while teaching make sure you are aware of issues regarding consent, legalities in your state, wishes of the parents, policies of your agencies and how your intervention will look to others.

Teach independence: It is natural for parents to want to protect their child with ASD but to avoid sex education and relationship development may actually make the individual vulnerable to dependency. Teach independence on skills that are transferable to sex education:

- personal hygiene

- dressing

- toileting

- use of a cell phone

- who and how to call in an emergency

Don’t do anything for them that they can do for themselves. This will help the child be less dependent on others for “help” and able to make their own decisions.

Teach safety skills: . Children with ASD are typically taught compliance, They may not know how to self-advocate and say “No” because they have been rewarded for compliance and listening to people who are “in charge”.

- Teach them to say “NO” when asked to do something they do not want to do (i.e. “No thank you, I do not want a hug”).

- Teach them that “Your body belongs to you” and rules for touching (appropriate vs inappropriate touches). They need to know they have rights over their bodies and how to “report” any inappropriate sexual behaviors or abuse.

Teach the obvious: Most children learn from a variety of sources: family, peers, TV, movies, internet etc. Those on the spectrum may not pick up on all this information. They may need things spelled out for them in a concrete literal fashion. “You cannot date women younger than 18”. Avoid or explain confusing language. “A “hook-up” is slang for meeting someone for sex and not a relationship.”

Teach about relationships: Explain the variety of relationships that people have (friendship vs love vs intimacy) and (close family and friends vs professionals, acquaintances, and strangers). Help them be social, learn social communication skills, and make friendships. Best friendships form from common interests (e.g., video games, “Anime”, trains etc.). The internet can help you find special interest groups and meet ups. There are also speed dating and singles groups for those with ASD.

Teach them about themselves: They need to develop self-esteem and a healthy self-concept. Understanding their diagnosis, strengths and weaknesses will help them be better advocates for themselves. Being a better self-advocate will also help protect their sexual well-being.

Randy Horowitz, M.S. Ed., S.A.S.

Randy has a Master of Science in Education from Queens College and a Certificate of School Administration and Supervision from the College of New Rochelle. Randy is currently a doctoral candidate in the educational leadership program at Concordia University. Randy started her career as a special education teacher in public school in Nassau County and then spent close to 30 years in senior leadership positions at nonprofit organizations serving children and adults with autism in NYC and Long Island. Randy has presented at local, national and international conferences on topics relating to educating individuals with autism. Her particular areas of interest include preparing and supporting individuals with autism for integration into community activities.

In addition to her many work responsibilities, Randy is also a seasoned runner and has participated in countless road races and marathons, including our Blazing Trails Run/Walk, raising well over $65,000 in the past 15 years to benefit the autism community.

Joanne Capuano Sgambati, Ph.D., BCBA-D, LBA

Dr. Sgambati serves as the Director of Psychological Services for Eden II’s Genesis Programs on LI. She specializes in consulting, counseling, evaluations, and behavior management of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). For the past 30 years, she has been dedicated to using positive behavior approaches, applied behavior analysis (ABA), for enhancing the lives of students in special education and adults on the autism spectrum. Dr. Sgambati is an active participant in Eden II’s Genesis Outreach Department conducting live presentations and webinars on a variety of topics at organizations, conferences, schools, and universities. She also conducts training seminars for local schools and various parent organizations. Dr. Sgambati specializes in ABA interventions for families of children and adults with special needs who demonstrate challenging behaviors. She is also the proud parent of two young adults on the Autism Spectrum.

Resources:

https://researchautism.org/sex-ed-guide/

https://www.autismspeaks.org/sites/default/files/2018-08/Puberty%20and%20Adolescence%20Resource.pdf

https://www.autismspeaks.org/recognizing-and-preventing-sexual-abuse

Ames, H. & Samowitz, P. (1995). Inclusionary standards for determining sexual consent for individuals with developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation, 4, 264-268.

Davies, C., Dubie, M. (2012). Intimate Relationships & and Sexual Health: A Curriculum for Teaching Adolescents/Adults with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders and Other Social Challenges.

Griffiths, D. (1999) Sexuality and developmental disabilities: Mythconceptions and facts. In I. Brown and M. Percy, (Eds.). Developmental Disabilities in Ontario (pp. 443-451). Toronto: Front Porch Publishing.

Griffiths, D.M., Richards, D. , Fedoroff, P., & Watson, S.L. (Eds.) 2002. Ethical dilemmas: Sexuality and developmental disabilities. NADD Press: Kingston, NY

Hanault, I. (2006). Asperger’s Syndrome and Sexuality: from Adolescence through Adulthood. (information and lessons for students on the less cognitively impaired end of the spectrum)

McLaughlin, K., Topper, K., & Lindert, J. (2010). Sexuality Education for Adults with Developmental Disabilities, Second Edition. (structured group model) Schwier, K.M., & Hingsberger, D. (2000). Sexuality: Your sons and daughters with intellectual disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing