This week, we’re thrilled to bring you a second guest article by Sarah Kupferschmidt, MA, BCBA. Sarah has written a very comprehensive article on teaching street safety skills in children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Learning to navigate the real world involves many complex skills that we may often take for granted. So how do we teach our children when to cross the street and what to watch out for? Read on for Sarah’s tips on how to teach and reinforce safety skills in children.

I am passionate about empowering children with special needs and their families with skills and knowledge that they can use to improve their quality of life. This is why I am super excited to be sharing tips and strategies that relate to keeping your child with autism safe on the street. Learning to navigate the real world involves a lot of complex skills that we sometimes take for granted. For example, learning to determine when it is safe to cross the street requires the ability to attend to your environment, the ability to identify moving cars from cars that are still, the ability to identify the signal at the cross walk that lets you know it is safe to cross, among many, many, more. In some cases even more advanced problem solving is required because if the sign says it is safe to cross and a motorist continues through the intersection we need to be able to identify the moving car is approaching and that we need to wait for it to pass before crossing the street. So where do we begin?

I am passionate about empowering children with special needs and their families with skills and knowledge that they can use to improve their quality of life. This is why I am super excited to be sharing tips and strategies that relate to keeping your child with autism safe on the street. Learning to navigate the real world involves a lot of complex skills that we sometimes take for granted. For example, learning to determine when it is safe to cross the street requires the ability to attend to your environment, the ability to identify moving cars from cars that are still, the ability to identify the signal at the cross walk that lets you know it is safe to cross, among many, many, more. In some cases even more advanced problem solving is required because if the sign says it is safe to cross and a motorist continues through the intersection we need to be able to identify the moving car is approaching and that we need to wait for it to pass before crossing the street. So where do we begin?

Tip #1: The Learner is Never Wrong

I love the saying “the learner is never wrong” because of what it implies. Whenever considering teaching a new skill to a child or student we need to focus on that unique child’s strengths and weaknesses. Where do we need to boost up their skills and what do they already know so that we can capitalize on those strengths. Before going out to teach your child with autism how to cross the street safely, they should have some imitation skills, be able to respond to instructions and attend to you or a teacher amidst a lot of distractions (e.g., cars, background noise and pedestrians, just to name a few). Once you have determined they are ready to learn this important skill you would want to use things that are of interest to them and that you know align with their learning style. For example, are they a visual learner and if so, how can you incorporate visuals to maximize their learning potential in how you go out and practice crossing the street safely?

Tip #2: Simplify the Complex Skills

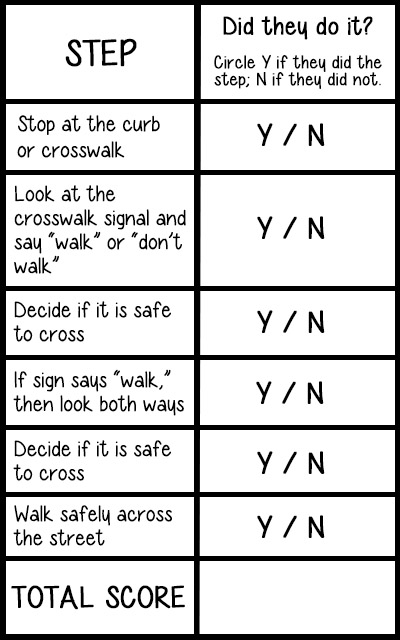

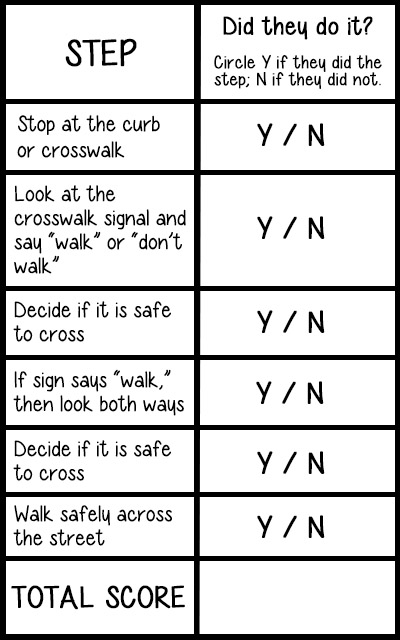

As mentioned earlier in the post, many of the skills that we use actually have many components, something we take for granted. In this case, teaching how to cross the street might involve the following steps:

- Stop at the curb/crosswalk

- Look at the crosswalk signal

- Decide if it is safe to cross (e.g., does it say ‘walk,’ or does it say ‘stop’)

- If the sign says walk, then look both ways

- Decide if it is safe (e.g., is there a car moving or not)

- Walk safely across the street (e.g., this means walking not running, perhaps holding your hand)

It is important to remember that these steps are just an example of what you might teach. You would individualize this based on the environment in which you live (e.g., if there is a crosswalk sign or crossing guard, or not) and the expectations you have as a family (e.g., to hold the hand or not). Teach this using tools that you know are effective with your unique child. For example, you may decide to print out a visual depiction for each of the steps and show them as you talk about it and practice. This depends on your child’s unique learning style. As with every skill that that we teach, it is never enough to just tell someone or show someone how to do it. We need to actually go out and practice.

Tip #3: Practice, Practice, Practice

Use every opportunity that you have to go out and practice this very important skill. I would also recommend that you set up specific times to go out and practice. You can use the visuals that you printed and go through each of the steps while you are out. If you notice that your child is struggling on a particular step, then practice that particular step at home even more. For example, if your child is not identifying the walk signal when you are out on the street, set up times to go over that at home.

Tip #4: Monitor Progress

In order to see how your child is doing on each of the steps it is a good idea to record how they do on each of the steps. You might print off a checklist with each of the steps that looks something like this:

You would calculate the number of times you recorded a Y over the total number of steps (e.g., in this case 6). For example, if I worked on this with my child and he did all of the steps he would get a 6/6. If he missed a step his overall score would be 5/6 or 83%. This score can then be used to monitor progress. I would also suggest that anytime you go out and practice you highlight whichever step(s) that they missed, if any. This will allow you to see if you need to work on something a little bit more before you go out and practice.

Tip #5: Notice the Good Stuff

Feedback is critical when you are teaching a new skill. Otherwise how is your child going to know how they are doing? This means that when they get it right we need to notice it and we need to be specific about what it is they did well. You can even use the visuals if you have them. You might say something like “I love the way you followed all of the steps of what to do when crossing the street safely! You stopped at the curb, looked at the signal…etc.” You may point to the visual as you tell them. If they missed a step remind them that next time they should try to remember what it is that they missed. Anytime they do one of the steps spontaneously, point it out to them and give lots of praise. Over time we can fade the praise out but it is really important when teaching a new skill, especially at the beginning.

If you have any questions about any of the tips listed here feel free to contact me or a local Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA). I am passionate about keeping our kids safe! Sign up for my newsletter or follow me on Twitter for regular tips and strategies!

WRITTEN BY SARAH KUPFERSCHMIDT, MA, BCBA

Sarah Kupferschmidt is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) who has worked with hundreds of children with autism and their families across Ontario. She has had the privilege of supervising ABA programs and training clinical staff in those programs. Currently Sarah offers parent coaching and workshops to teach parents but also educators on the most effective ways to teach children using the principles of ABA. She is also a part-time faculty member at Mohawk College in the Autism Behavioral Science program, in the social sciences program at McMaster University, and an Adjunct Professor at Sage Graduate School. Sarah is CEO and co-Founder of Special Appucations, Inc. which is a company that creates educational products that help maximize the learning potential for children with autism because they are designed using the principles of ABA. Sarah has appeared as a guest on CP24, CHCH news, Hamilton Life and the Scott Thompson radio show as an authority on autism.

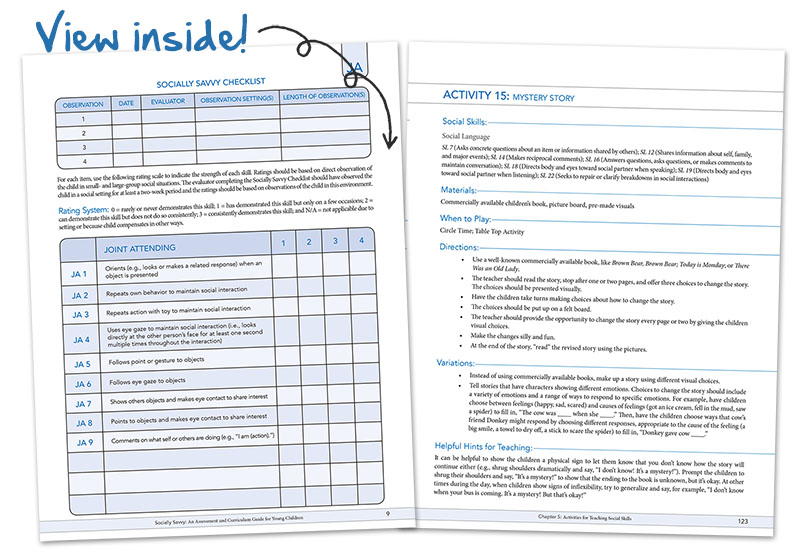

Assessing Language and Learning with Pictures (ALL PICS) is an assessment tool designed to be used in conjunction Dr. Mark Sundberg’s Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP). ALL PICS was designed by behavior analysts who specialize in the application of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior and have extensive experience in assessing verbal behavior with assessments such as the VB-MAPP.

Assessing Language and Learning with Pictures (ALL PICS) is an assessment tool designed to be used in conjunction Dr. Mark Sundberg’s Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP). ALL PICS was designed by behavior analysts who specialize in the application of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior and have extensive experience in assessing verbal behavior with assessments such as the VB-MAPP. ALL PICS consists of 3 spiral bound books, with pre-arranged fields of high-resolution images that correspond with the VB-MAPP specifications. While conducting a verbal behavior assessment, the evaluator using ALL PICS can quickly record responses on the corresponding downloadable data sheets and then turn from one page of the book to the next. For visual tasks, a corresponding box of labeled flashcards is included, permitting the tester to quickly obtain all cards needed for each milestone without the need to search for cards.

ALL PICS consists of 3 spiral bound books, with pre-arranged fields of high-resolution images that correspond with the VB-MAPP specifications. While conducting a verbal behavior assessment, the evaluator using ALL PICS can quickly record responses on the corresponding downloadable data sheets and then turn from one page of the book to the next. For visual tasks, a corresponding box of labeled flashcards is included, permitting the tester to quickly obtain all cards needed for each milestone without the need to search for cards.

Noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) is the presentation of reinforcement independent of behavior, and there are many studies out there that demonstrate it can have a significant impact on behavior.

Noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) is the presentation of reinforcement independent of behavior, and there are many studies out there that demonstrate it can have a significant impact on behavior.

Recently I was working with a family to toilet train their son Jonathan, a six-year-old with autism. (Names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect confidentiality.) When he eliminated in the toilet, part of his reinforcement was getting to watch the water go down the toilet after flushing. At some point, he developed the behavior of putting his hands into the toilet water as it was flushing.

Recently I was working with a family to toilet train their son Jonathan, a six-year-old with autism. (Names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect confidentiality.) When he eliminated in the toilet, part of his reinforcement was getting to watch the water go down the toilet after flushing. At some point, he developed the behavior of putting his hands into the toilet water as it was flushing.

The lids easily twist off and on, and the solid lids hold liquid securely inside. The tubes measure 12 inches in height and 2.5 inches in diameter. These Sensory Tubes will make your student’s reinforcement possibilities endless!

The lids easily twist off and on, and the solid lids hold liquid securely inside. The tubes measure 12 inches in height and 2.5 inches in diameter. These Sensory Tubes will make your student’s reinforcement possibilities endless! I am passionate about empowering children with special needs and their families with skills and knowledge that they can use to improve their quality of life. This is why I am super excited to be sharing tips and strategies that relate to keeping your child with autism safe on the street. Learning to navigate the real world involves a lot of complex skills that we sometimes take for granted. For example, learning to determine when it is safe to cross the street requires the ability to attend to your environment, the ability to identify moving cars from cars that are still, the ability to identify the signal at the cross walk that lets you know it is safe to cross, among many, many, more. In some cases even more advanced problem solving is required because if the sign says it is safe to cross and a motorist continues through the intersection we need to be able to identify the moving car is approaching and that we need to wait for it to pass before crossing the street. So where do we begin?

I am passionate about empowering children with special needs and their families with skills and knowledge that they can use to improve their quality of life. This is why I am super excited to be sharing tips and strategies that relate to keeping your child with autism safe on the street. Learning to navigate the real world involves a lot of complex skills that we sometimes take for granted. For example, learning to determine when it is safe to cross the street requires the ability to attend to your environment, the ability to identify moving cars from cars that are still, the ability to identify the signal at the cross walk that lets you know it is safe to cross, among many, many, more. In some cases even more advanced problem solving is required because if the sign says it is safe to cross and a motorist continues through the intersection we need to be able to identify the moving car is approaching and that we need to wait for it to pass before crossing the street. So where do we begin?

In general, when we make choices about how to behave, whether we are aware of it or not, we choose the behavior that gets the best results with the least response effort. But if a low response effort achieves poor results, we’re probably not going to engage in that behavior. Let’s look at an example of choosing a higher response effort. Let’s say I live down the street from a hair salon, and I go there once but hate my hair cut. I’ll engage in the higher response effort to drive 30 minutes to a salon that gives me a great cut. I want the lowest response effort, but not if it achieves poor results.

In general, when we make choices about how to behave, whether we are aware of it or not, we choose the behavior that gets the best results with the least response effort. But if a low response effort achieves poor results, we’re probably not going to engage in that behavior. Let’s look at an example of choosing a higher response effort. Let’s say I live down the street from a hair salon, and I go there once but hate my hair cut. I’ll engage in the higher response effort to drive 30 minutes to a salon that gives me a great cut. I want the lowest response effort, but not if it achieves poor results.