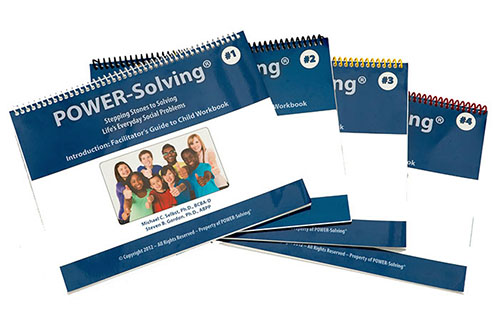

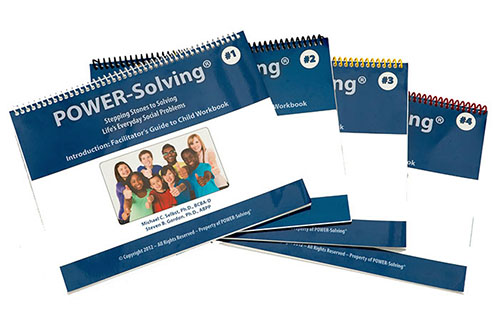

In continuing our exclusive social problem-solving series, Drs. Gordon and Selbst, developers of the new POWER-Solving® Curriculum, have addressed the importance of social information processing as a framework for understanding how children and adolescents get along with their peers and adults.

The Social Problem-Solving Model: Promoting Greater Independence – Part II

Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP & Michael C. Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D

Social Information Processing (SIP) is a widely studied framework for understanding why some children and adolescents have difficulty getting along with their peers and adults.

Social Information Processing (SIP) is a widely studied framework for understanding why some children and adolescents have difficulty getting along with their peers and adults.

A well-known SIP model developed by Crick and Dodge (1994) describes six stages of information processing that individuals cycle through when responding to a particular social situation:

- encoding (attending to and encoding the relevant cues);

- interpreting (making a judgment about what is going on);

- clarifying goals (deciding what their goal is in the particular situation);

- generating responses (identifying different behavioral strategies for attaining the decided upon goal);

- deciding on the response (evaluating the likelihood that each potential strategy will help reach their goal, and choosing which strategy to implement);

- and performing the response (doing the chosen response).

These steps operate in real time and frequently outside of conscious awareness. Many studies have demonstrated that children and adolescents have deficits at multiple stages of the SIP model which impact their development of appropriate peer interactions and the development of aggressive behaviors (Lansford, Malone, Dodge, Crozier, Pettit and Bates, 2006).

As a result, they have difficulty attending to and interpreting social cues, adopting pro-social goals and utilizing safe, effective and non-aggressive strategies to handle conflict situations. The development of strong social skills has been shown to contribute to the initiation and maintenance of positive relationships with others.

The POWER-Solving® Curriculum (Selbst and Gordon, 2012) is heavily influenced by the components of the SIP model as seen in the five steps of POWER-Solving, easily learned in the acronym POWER:

The POWER-Solving® Curriculum (Selbst and Gordon, 2012) is heavily influenced by the components of the SIP model as seen in the five steps of POWER-Solving, easily learned in the acronym POWER:

- Put the problem into words;

- Observe your feelings;

- Work out your goal;

- Explore possible solutions;

- Review your plan

The curriculum is comprised of several modules, each with their own materials for facilitators and students. While it is critical for the student to learn the POWER-Solving® Steps first (i.e., the “toolbox”), the facilitator can determine the sequence of the subsequent modules. For example, one may prefer to move to the Anger Management module after the introduction. Alternatively, one may decide to move to Social Conversation or Developing Friendships. The goal is for students to learn valuable POWER-Solving skills that they can apply to an infinite number of social situations throughout their lives.

REFERENCES

Crick, N.R., & Dodge, K.A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74.

Lansford, J.E., Malone, P.S., Dodge, K.A., Crozier, J.C., Pettit, G.S., & Bates, J.E. (2006). A 12-year prospective study of patterns of social information processing problems and externalizing behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 715-724.

Selbst, M.C. and Gordon, S.B. (2012). POWER-Solving: Stepping stones to solving life’s everyday social problems. Somerset, NJ: Behavior Therapy Associates.

ABOUT STEVEN B. GORDON, PHD, ABPP

Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP is the Founder and Executive Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a clinical psychologist and is licensed in New Jersey. Dr. Gordon is also Board Certified in Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology by the American Board of Professional Psychology and is a Diplomate in Behavior Therapy from the American Board of Behavioral Psychology. Dr. Gordon has co-authored three books, published numerous articles, presented papers at local and national conferences, and served on editorial boards of professional journals. Most recently, Dr. Gordon and Dr. Selbst have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program POWER-Solving: Stepping Stones to Solving Life’s Everyday Social Problems. Dr. Gordon’s professional interests range from providing assessment and treatment for individuals diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders, AD/HD and other disruptive behavior disorders associated with childhood and adolescence. He has co-founded and is the Executive Director of HI-STEP® Summer Program, which is an intensive five-week day program for children to improve their social skills and problem solving ability. In addition, Dr. Gordon has had extensive experience providing clinical services not only for children diagnosed with phobias, stress, selective mutism, obsessive compulsive disorders and depression, but also with adults coping with anxiety,depression and relationship difficulties. Dr. Gordon is a member of the American Psychological Association, the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, and the New Jersey Psychological Association.

Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP is the Founder and Executive Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a clinical psychologist and is licensed in New Jersey. Dr. Gordon is also Board Certified in Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology by the American Board of Professional Psychology and is a Diplomate in Behavior Therapy from the American Board of Behavioral Psychology. Dr. Gordon has co-authored three books, published numerous articles, presented papers at local and national conferences, and served on editorial boards of professional journals. Most recently, Dr. Gordon and Dr. Selbst have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program POWER-Solving: Stepping Stones to Solving Life’s Everyday Social Problems. Dr. Gordon’s professional interests range from providing assessment and treatment for individuals diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders, AD/HD and other disruptive behavior disorders associated with childhood and adolescence. He has co-founded and is the Executive Director of HI-STEP® Summer Program, which is an intensive five-week day program for children to improve their social skills and problem solving ability. In addition, Dr. Gordon has had extensive experience providing clinical services not only for children diagnosed with phobias, stress, selective mutism, obsessive compulsive disorders and depression, but also with adults coping with anxiety,depression and relationship difficulties. Dr. Gordon is a member of the American Psychological Association, the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, and the New Jersey Psychological Association.

ABOUT MICHAEL C. SELBST, PHD, BCBA-D

Michael C. Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D is Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a Licensed Psychologist and a Certified School Psychologist in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. He is also a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral level. Dr. Selbst has co-founded and is the Executive Director of HI-STEP® Summer Program, which is an intensive five-week day program for children to improve their social skills and problem solving ability, and the Director of the Weekend to Improve Social Effectiveness (W.I.S.E.). He has extensive experience working with pre-school aged children through adults, including individuals who have social skills deficits, emotional and behavioral difficulties, learning disabilities, gifted, and children with developmental delays, including those with Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome. Dr. Selbst consults to numerous public and private schools, assisting parents, teachers, and mental health professionals, and presents workshops on all topics highlighted above, as well as Parenting Strategies, Depression, and Suicide Prevention. Dr. Selbst and Dr. Gordon have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program POWER-Solving: Stepping Stones to Solving Life’s Everyday Social Problems. Dr. Selbst is a member of the following professional organizations: American Psychological Association; National Association of School Psychologists; Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Association for Behavior Analysis International; Association for Contextual Behavioral Science; New Jersey Psychological Association; and New Jersey Association of School Psychologists.

Michael C. Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D is Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a Licensed Psychologist and a Certified School Psychologist in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. He is also a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral level. Dr. Selbst has co-founded and is the Executive Director of HI-STEP® Summer Program, which is an intensive five-week day program for children to improve their social skills and problem solving ability, and the Director of the Weekend to Improve Social Effectiveness (W.I.S.E.). He has extensive experience working with pre-school aged children through adults, including individuals who have social skills deficits, emotional and behavioral difficulties, learning disabilities, gifted, and children with developmental delays, including those with Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome. Dr. Selbst consults to numerous public and private schools, assisting parents, teachers, and mental health professionals, and presents workshops on all topics highlighted above, as well as Parenting Strategies, Depression, and Suicide Prevention. Dr. Selbst and Dr. Gordon have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program POWER-Solving: Stepping Stones to Solving Life’s Everyday Social Problems. Dr. Selbst is a member of the following professional organizations: American Psychological Association; National Association of School Psychologists; Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Association for Behavior Analysis International; Association for Contextual Behavioral Science; New Jersey Psychological Association; and New Jersey Association of School Psychologists.

Social Information Processing (SIP) is a widely studied framework for understanding why some children and adolescents have difficulty getting along with their peers and adults.

Social Information Processing (SIP) is a widely studied framework for understanding why some children and adolescents have difficulty getting along with their peers and adults. The

The  Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP is the Founder and Executive Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a clinical psychologist and is licensed in New Jersey. Dr. Gordon is also Board Certified in Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology by the American Board of Professional Psychology and is a Diplomate in Behavior Therapy from the American Board of Behavioral Psychology. Dr. Gordon has co-authored three books, published numerous articles, presented papers at local and national conferences, and served on editorial boards of professional journals. Most recently, Dr. Gordon and Dr. Selbst have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program

Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP is the Founder and Executive Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a clinical psychologist and is licensed in New Jersey. Dr. Gordon is also Board Certified in Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology by the American Board of Professional Psychology and is a Diplomate in Behavior Therapy from the American Board of Behavioral Psychology. Dr. Gordon has co-authored three books, published numerous articles, presented papers at local and national conferences, and served on editorial boards of professional journals. Most recently, Dr. Gordon and Dr. Selbst have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program  Michael C. Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D is Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a Licensed Psychologist and a Certified School Psychologist in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. He is also a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral level. Dr. Selbst has co-founded and is the Executive Director of HI-STEP® Summer Program, which is an intensive five-week day program for children to improve their social skills and problem solving ability, and the Director of the Weekend to Improve Social Effectiveness (W.I.S.E.). He has extensive experience working with pre-school aged children through adults, including individuals who have social skills deficits, emotional and behavioral difficulties, learning disabilities, gifted, and children with developmental delays, including those with Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome. Dr. Selbst consults to numerous public and private schools, assisting parents, teachers, and mental health professionals, and presents workshops on all topics highlighted above, as well as Parenting Strategies, Depression, and Suicide Prevention. Dr. Selbst and Dr. Gordon have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program

Michael C. Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D is Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a Licensed Psychologist and a Certified School Psychologist in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. He is also a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral level. Dr. Selbst has co-founded and is the Executive Director of HI-STEP® Summer Program, which is an intensive five-week day program for children to improve their social skills and problem solving ability, and the Director of the Weekend to Improve Social Effectiveness (W.I.S.E.). He has extensive experience working with pre-school aged children through adults, including individuals who have social skills deficits, emotional and behavioral difficulties, learning disabilities, gifted, and children with developmental delays, including those with Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome. Dr. Selbst consults to numerous public and private schools, assisting parents, teachers, and mental health professionals, and presents workshops on all topics highlighted above, as well as Parenting Strategies, Depression, and Suicide Prevention. Dr. Selbst and Dr. Gordon have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program

NBC’s Dateline recently aired “On the Brink,” a 3-year chronicle of two New York-based young adults with autism and the emotional journeys their families have endured. As they transition from graduation to adulthood, they make a leap towards the unexpected future.

NBC’s Dateline recently aired “On the Brink,” a 3-year chronicle of two New York-based young adults with autism and the emotional journeys their families have endured. As they transition from graduation to adulthood, they make a leap towards the unexpected future. This report puts a spotlight on autism’s “aging out” crisis. “On the Brink” presents a deeper look at the lives of young adults with autism and the measures parents must take to provide their children with specialized services and a better future when they turn 21. Both families featured in this episode fight to help their children and revolutionize the way autism is perceived in the U.S.

This report puts a spotlight on autism’s “aging out” crisis. “On the Brink” presents a deeper look at the lives of young adults with autism and the measures parents must take to provide their children with specialized services and a better future when they turn 21. Both families featured in this episode fight to help their children and revolutionize the way autism is perceived in the U.S.

Recently I was working with a family to toilet train their son Jonathan, a six-year-old with autism. (Names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect confidentiality.) When he eliminated in the toilet, part of his reinforcement was getting to watch the water go down the toilet after flushing. At some point, he developed the behavior of putting his hands into the toilet water as it was flushing.

Recently I was working with a family to toilet train their son Jonathan, a six-year-old with autism. (Names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect confidentiality.) When he eliminated in the toilet, part of his reinforcement was getting to watch the water go down the toilet after flushing. At some point, he developed the behavior of putting his hands into the toilet water as it was flushing.