Teaching language skills is one of the most frequent needs for children with autism, but also one of the most misunderstood skillsets amongst both parents and practitioners. The desire to hear your learner speak in full sentences can be overwhelming, making it especially difficult to take a step back and consider what it means to communicate and how communication skills develop in neurotypical children. Many times we get hung up on what a child should be capable of communicating at a certain age, rather than focusing on what they are capable of communicating at this stage of development.

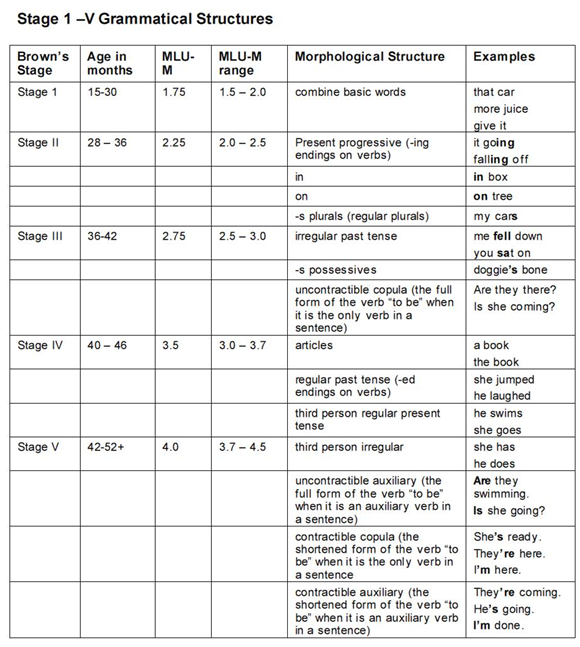

Many practitioners and curricula utilize Brown’s Stages of Language Development.* Brown described the first five stages of language development in terms of the child’s “mean length of utterance” (or MLU) as well as the structure of their utterances.

From aacinstitute.org

From aacinstitute.org

Sometimes it is necessary to compare a child to his or her same-age peers in order to receive services or measure progress, but it can be detrimental to focus on what a child should be doing at a specific age instead of supporting them and reinforcing them for progress within their current stage.

Research has suggested that teaching beyond the child’s current stage results in errors, lack of comprehension, and difficulty with retention. Here are some common errors you may have witnessed:

- The child learns the phrase “I want _____ please.” This phrase is fine for “I want juice, please” or “I want Brobee, please,” but it loses meaning when overgeneralized to “I want jump, please” or “I want play, please.” It’s better to allow your learner to acquire hundreds of 1-2 word mands (or requests) before expecting them to speak in simple noun+verb mands.

- The child learns to imitate only when the word “say” is used. Then the child makes statements such as “say how are you today,” as a greeting or “say I’m sorry,” when they bump into someone accidentally. Here, the child clearly has some understanding of when the phrases should be used without understanding the meanings of the individual words within each phrase.

- The child learns easily overgeneralized words such as “more.” This is useful at times, but the child can start using it for everything. Instead of saying “cookie” he’ll say “more.” Instead of saying “train,” he’ll say “more.” And he may say “more” when the desired item is not present, leaving the caregiver frustrated as he/she tries to guess what the child is requesting. Moreover, as language begins to develop, he may misuse it by saying things such as “more up, please.”

- The child learns to say “Hello, how are you today?” upon seeing a person entering a room. A child comes into the classroom and the learner looks up, says “Hello, how are you today?” The child responds, “Great! Look at the cool sticker I got!” Your learner then doesn’t respond at all, or may say “fine,” as he has practiced conversations of greeting.

These are only a few of the common language errors you may see. While you may want your learner to speak in longer sentences, your goal should be to have them communicate effectively. With this goal in mind, it becomes essential to support them at their current stage, which means it’s essential to assess them and understand how to help them make progress.

This is why I always use the VB-MAPP to assess each child and make decisions about language instruction. I need to have a full understanding of how the learner is using language, and then move them through each stage in a clear progression. I may want the child to say “Hello, how are you today?” But when I teach them that, do they understand those individual words? Do they comprehend what today means as opposed to yesterday or tomorrow? Do they generalize the use of “how” to other questions?

As you make treatment decisions for your learner, think about their current stage and talk about how to support your child with both a Speech Language Pathologist and an ABA therapist.

*Brown, R. (1973). A first language: The early stages. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

WRITTEN BY SAM BLANCO, MSED, BCBA

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-15 in NYC. Working in education for twelve years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam utilizes strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently a PhD candidate in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College. She is also a lecturer in the ABA program at The Sage Colleges.

J. Tyler Fovel, MA, BCBA’s essential manual for creating professional and effective ABA programs blends clear explanations of scientifically-based concepts and methodology, clinical examples and advice, and suggested implementation strategies. This revised edition presents information on:

J. Tyler Fovel, MA, BCBA’s essential manual for creating professional and effective ABA programs blends clear explanations of scientifically-based concepts and methodology, clinical examples and advice, and suggested implementation strategies. This revised edition presents information on: