Category Archives: Applied Behavior Analysis

Introducing The Self & Match System!

Different Roads is thrilled to be adding The Self & Match System to our lineup! Created by Jamie S Salter ED.S, BCBA and Katharine M Croce ED.D, BCBA-D, Self & Match is a self-monitoring and motivational system firmly grounded in principles of ABA. This behavioral intervention encourages a collaborative approach to promoting behavioral success for children & young adults, using self-monitoring with a match component. Self & Match is a data-based and interactive intervention!

Interdisciplinary Collaboration and ABA

This week, Dr. Val Demiri PhD, BCBA-D, LBA offers some helpful advice on how to improve collaboration between professionals from different disciplines.

As professionals, collaborating with others in your work environment is an essential skill that may have been historically overlooked as part of the specific training you received as a behavior analyst. Currently, becoming credentialed as a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) does not entail any coursework requirement in collaboration, however collaboration is mentioned as part of the Behavior Analysis Certification Board (BACB) 4th Edition Task List under Section II, and The BACB Code of Ethics as follows:

TASK LIST Section II: Client-Centered Responsibilities

G-06: Provide behavior-analytic services in collaboration with others who support and/or provide services to one’s clients.

BACB CODE: 2.0 – Behavior Analysts responsibility to clients:

2.03 (b) When indicated and professionally appropriate, behavior analysts cooperate

with other professionals, in a manner that is consistent with the philosophical

assumptions and principles of behavior analysis, in order to effectively and

appropriately serve their clients.

BACB CODE: 7.0 Behavior Analysts’ Ethical Responsibility to Colleagues.

Behavior analysts work with colleagues within the profession of behavior analysis and

from other professions and must be aware of these ethical obligations in all situations.

(See also, 10.0 Behavior Analysts’ Ethical Responsibility to the BACB)

These current ethical codes and task lists must be adhered to by behavior analysts and should raise questions on how to obtain the skills required for collaboration. Because we are an evidence-based and empirically oriented field, we may often find ourselves in the midst of conflict when presented with non-behavioral and non-evidence based treatments to our clients that other professions may be using or want to use. How do we resolve the ethical dilemma in the best interest of our client?

One suggestion is to seek supervision and training in collaboration. Over the years, the need for training (both didactic and hands-on) on collaboration with other professions has increased. Perhaps perspective and understanding of other professions and their ideologies are good places to start so that we put ourselves in better positions to present our understanding of what will help our client. Let’s face it, behavior analysis can seem stuffy and arrogant, if not cold, to other professions who pride themselves in helping clients and building connections and who may have little understanding of our field.

The research on collaboration is beginning to emerge within our field (Kelly & Tincani, 2013; Broadhead, 2015) and we can certainly look to fields outside of ABA who have taken it upon themselves to educate their profession on what applied behavior analysis is and how to forge collaborations as well as find common ground between fields (Donaldson & Stahmer, 2014). Donaldson & Stahmer (2014) published an article explaining the philosophy and principles of ABA to the speech and language profession, while also emphasizing common ground, mutual objectives and understanding of ABA. Within our own field, some initial steps in understanding collaboration was undertaken by Kelly and Tincani (2013) who conducted a survey of behavior analysts regarding collaboration using the following definition:

“A component of consultation involving voluntary, interpersonal interactions comprising of two or more professionals engaging in communication modalities for the purposes of shared decision-making and problem solving toward a common goal and resulting in changes to tasks and solutions that would not have been achieved in isolation.”

Not surprisingly, the survey revealed that 67% of respondents reported no coursework with “collaboration” in the coursework title and most surveyed agreed that they would want more training in collaboration (Kelly & Tincani, 2013). Even more striking were findings suggesting that behavior analysts were not necessarily team players during the collaboration process as collaboration was reported to be uni-directional (Kelly and Tincani, 2013). Unfortunately, the lack of collaboration may subsequently create conditions in which interventions are less likely to be implemented, simply because other professionals involved in the care of the client were not part of the decision making for those interventions (Kelly & Tincani, 2013).

More so than ever before, researchers, clinicians and educators find themselves working in settings with diverse professional disciplines that are responsible for treating the same individual. Nowhere is this example made clearer for behavior analysts than the settings in which a host of related services from varying professions are provided to students as part of their Individualized Education Plan (IEP). Understanding the dilemmas that behavior analysts might be faced with in terms of evidence-based interventions that are empirically sound, Broadhead (2015) offered a decision-making model for determining whether or not the proposed non-behavioral treatment is worth addressing. Broadhead (2015) suggested that gaining skills in systematically evaluating whether or not you question a treatment (which runs the risk of eroding relationships) vs. not addressing clearly dangerous and unhelpful therapies that have been debunked, (e.g., facilitated communication) can serve as clear guidance and decision making strategies when faced with such ethical dilemmas.

Understanding collaboration and gaining the skills needed to collaborate across disciplines should be both a professional goal and a goal within our field. In that spirit, the following tips for collaboration are offered:

1) Get to know the profession of others you work with in your setting. Ask for and offer others basic readings about your field, philosophy, and profession.

2) Talk about your own training and how you learned the skills you have and ask questions about training that other professionals have received in their field and how they came to acquire their skill set.

3) Be honest about philosophical underpinnings of how you have been trained (e.g., behaviorism, applied behavior analysis).

4) Discuss common goals you have for your client and how you can collaborate.

5) If appropriate, ask for a demonstration of a strategy or intervention, so you can see for yourself what is being done and offer to show how you would implement interventions for the same goal and discuss the commonalities or differences in strategies.

6) Set regular collaboration meetings and have an agenda where concerns, successes and progress are discussed.

7) Agree on a plan of intervention as a team.

8) Offer help with your skills that are applicable across all fields–such as data collection strategies, graphing, operational definitions, measurement of behavior, skill acquisition and progress.

9) Create a collaboration goal with someone outside your field.

10) Stay open to learning from others without compromising your ethical obligations as a professional and seek supervision.

Board, B. A. C. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts.

Brodhead, M.T., (2015). Maintaining Professional Relationships in an Interdisciplinary Setting:

Strategies for Navigating Nonbehavioral Treament Recommendations for Individuals

with Autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8: 70-78.

Donaldson, A., & Stahmer, A. C. (2014). Team Collaboration: The use of Behavior Principles for

serving students with ASD. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 45: 261–

276

Kelly, A., & Tincani, M. (2013). Collaborative training and practice among applied behavior

analysts who support individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training

in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 120-131.

About The Author

Dr. Demiri received her doctorate in Clinical and School Psychology from Hofstra University in 2004 and her Board Certification in Behavior Analysis (BCBA) from Rutgers University in 2005. She currently serves as an adjunct professor at Endicott College in the Van Loan School of Graduate & Professional Studies and she is the district-wide behavior specialist at Hopewell Valley Regional School District in New Jersey. Previously she served as the Assistant Director of Outreach Services at the Douglass Developmental Disabilities Center of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, where she spearheaded the Early Intervention Program. Her professional interests include diagnostic assessments, language and social skills development in individuals with autism spectrum disorders as well as international dissemination of Applied Behavior Analysis. She has presented on Applied Behavior Analysis and autism locally, nationally and internationally. Val is the co-author of the book, Jumpstarting Communication Skills in Children with Autism: A Parent’s Guide to Applied Verbal Behavior: Woodbine House.

Pick of the Week: Take 20% off Super Sorting Tools!

Develop your learner’s sorting and matching skills with these tools and manipulatives!

*Promotion is valid until July 31st 2017 at 11:59pm ET. Offer cannot be applied to previous purchases, combined with any other offers, transferred, refunded, or redeemed and/or exchanged for cash or credit. Different Roads to Learning reserves the right to change or cancel this promotion at any time. To redeem offer at differentroads.com, enter promo code

SORT2017 at checkout.

Teaching Adaptive Skills

In this months’s ASAT feature, Diane Adreon, EdD answers a question about what to consider when helping a child gain independence. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook!

This article was originally published in ASAT’s free quarterly newsletter.

We are older parents and often lay awake at night worrying about our daughter’s ability to function independently when we are no longer able to care for her ourselves. She is 17 years old and is becoming more and more independent. We have read the “Hidden Curriculum” and that resource has opened our eyes to subtle social skills that may be missing in her repertoire. Are there adaptive skills that my wife and I should be considering that are often overlooked?

Individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) typically have an uneven profile of skills (Ehlers et al., 2007). Regardless of cognitive ability, individuals with ASD often have difficulty with independent living skills. In fact, in many cases, areas of strength can mask significant deficits in adaptive skills. Adaptive behaviors are a reflection of the way an individual applies his or her cognitive skills in actual life situations. Research has shown that individuals with ASD have significantly lower adaptive behavior functioning than their measured cognitive abilities (Klin et al., 2007; Lee & Park, 2007; Mazefsky, Williams, & Minshew, 2007; Myles et al., 2007). This suggests that, no matter the individual’s level of functioning, we need to focus on teaching adaptive skills.

When identifying what skills to teach, it is important to remember that goals should be individualized. Some questions to ask in identifying goals for your daughter include:

- Is the skill a reasonable one to teach given her age and her opportunities to perform the skill?

- Will she be transitioning to a new environment in the next few years? If so, what skills will she need to be successful in that environment?

- If your daughter is currently in a program that can address daily living skills, can the goals be formalized making them a part of her IEP or IHP?

The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System- Second Edition (ABAS-II; Harrison & Oakland, 2003), Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised (SIB-R; Bruininks, Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1997), or the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales- Second Edition (VABS-II; Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005) are all adaptive behavior assessment instruments that can yield information helpful in identifying goals. Although the overall scores will provide a global picture of your daughter’s adaptive skills, going over the specific items on the protocol will provide substantially more useful input in the identification of goals.

The science of applied behavior analysis (ABA) provides numerous strategies to assist in teaching skills. Baseline data supply information on current skill levels and can help identify target behaviors. A task analysis assists in breaking down complex tasks into smaller components and behavior chaining procedures can help determine which steps to teach first. In addition, behavioral shaping procedures and carefully constructed prompting hierarchies can help ensure that we are teaching skills in the most efficient and effective manner. Moreover, identifying reinforcers and using data to determine schedules of reinforcement can address motivational issues. Finally, teaching strategies to address generalization challenges can increase the likelihood of the individual learning to perform the skills in a variety of situations.

Since the scope of skills associated with independence is quite broad, the remainder of this response will focus on some adaptive skills that are often overlooked. When such skills are taught to individuals with ASD, they can become more independent.

Teach safe and practical money skills. When making purchases out in the community, it is a good idea to not “show” others how much money you have. Therefore, consider teaching your daughter practical strategies such as getting her money out of her wallet ahead of time, counting her money in her wallet and taking out just the amount of money she needs for a purchase. You may also want to teach her to make purchases using a debit card and the protocol for withdrawing money at an ATM. This includes teaching her to maintain an appropriate amount of space between her and others in the ATM line, putting the money into her wallet before walking away from the ATM, and so forth. It cannot be overstated that practice is essential for learning any of these skills. Some ways you can create more opportunities for your daughter to practice these skills include establishing a bank account and giving her a check for her allowance; thereby creating a reason for her to learn how to make deposits and withdrawals from an ATM. You can also have her practice making deposits and withdrawals inside the bank with a teller.

Teach your daughter to use a calendar to track upcoming events. For most of us, the number of things we need to remember increases significantly when entering adulthood. In addition, some of what we may need to remember occurs only periodically, and outside of our daily routines, thus it can be much harder to rely on one’s memory in those instances. Depending on your daughter’s level of functioning, your primary goal might be having her check her schedule to see what is happening that day or to prepare her for upcoming events and activities. In other instances, you can work with her on marking a calendar with upcoming events or reminders (e.g., return library book at school, swimming at Jake’s – bring swimming suit) and reviewing them daily. Teach her to get in the habit of referring to the calendar for information. Individuals with ASD need practice to use visual resources.

Teach your daughter to create and use her own to do list. Remember, a to-do list can use any kind of visual or cue so that your daughter understands what to do. Individuals of all functioning levels can learn to follow a to-do list if it is written at the appropriate level (may use pictures instead of words) and they have been taught to refer to it and do each task independently. For some, you may want to start early in having them write or type their to do list and learn to refer to it and check things off when done. It is also a good idea to help them identify and build in preferred activities to reinforce “work before play.”

Teach your daughter to take medication independently. Most of us use visual cues or create a routine to remind us to take our medication, so work to establish similar ones for your daughter. If the medication regime is complicated, consider using a weekly pill box and organizing the medication on Sundays. Or perhaps you have a visual reminder present at the breakfast table that says, “Take medication.” In some instances, this might mean having the medication bottle or pill box on the breakfast table. Establish the routine of having your daughter take the medication right before breakfast (if the prescription allows) as this will decrease the likelihood that she will forget it. Once you have introduced this routine, decrease your verbal reminders to take the medication and direct her attention to the visual reminder. If she has a smart phone, you can also teach her how to set up a daily reminder to take the medication at specific times.

Hopefully these suggestions and examples of possible targets have provided you with a few additional ideas on ways to ensure your daughter continues to make progress towards greater independence. Assessment of her skills across a number of domains (home, community, health, safety, and work) as well as reviewing her individual goals and progress on a regular basis can ensure an ongoing conversation about priority adaptive skills to help her continue moving\ forward. It does take time and practice, but the pay-off is worth it in the long run.

References

Bruininks, R. Woodcock, R., Weatherman, R., & Hill, B. (1997). Scales of Independent behavior-Revised. Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Ehlers, S., Nyden, A., Gilllberg,C., Sandberg, A. D., Dahlgren, S., Hjelmquist, E., & Odén, A., Jr. (1997). Asperger Syndrome, autism, and attention disorders: A comparative study of the cognitive profiles of 120 children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 38, 207-217.

Harrison, P. L., & Oakland, T. (2003). Adaptive Behavior Assessment Systems (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessment.

Klin, A., Saulnier, C. A., Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., Volkmar, F. R., & Lord, C. (2007). Social and communication abilities and disabilities in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: The Vineland and the ADOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 748-759.

Lee, H. J., & Park, H. R. (2007). An integrated literature review on the adaptive behavior of individuals with Asperger syndrome. Remedial and Special Education, 28, 132-139.

Mazefsky, C. A., Williams, D. L., & Minshew, N. J. (2008). Variability in adaptive behavior in autism: Evidence for the importance of family history. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 591-599.

Myles, B. S., Lee, H. J., Smith, S. M., Tien, K., Chou, Y., Swanson, T. C., & Hudson, J. (2007). A large scale study of the characteristics of Asperger syndrome. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 42, 448-459.

Sparrow, S., Cicchetti, D. & Balla, D. (2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessment.

About The Author

Dr. Adreon is the associate director of the University of Miami-Nova Southeastern University for Autism & Related Disabilities (UM-NSU CARD). She also has a private consulting practice specializing in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (www.spectrumlifestrategies.com, Info@spectrumlifestrategies.com)

Carefully Consider the Meaning of Independence

In working with individuals with autism, my goal is always to help them move towards independence. Recently, I was speaking with a colleague about an intervention I had done in which a child independently began his bedtime routine (brushing teeth, changing into pajamas, etc.) when his VibraLite watch vibrated at 8PM. When the watch vibrates, he resets it for 8PM the next day. Her response was that she didn’t believe that was truly independent behavior, since he required the prompt of the watch vibration. Many of you reading may agree with my colleague, but I think we must consider independence today in the context of our own behavior.

In the evening, I set an alarm clock, and I only wake up in the morning when it buzzes. When I run out of milk, I’ll put an alert in my Reminders app on my phone. When a friend invites me to lunch, I immediately enter the date in my calendar. All of these are technically examples of prompts, but if I am managing the prompts, I would argue that I am in fact engaging in independent behavior.

When I think about independent behavior, I want the children I work with to one day be able to grocery shop, go to work, eat a meal with a sibling, and more without having another adult facilitate those interactions. I want them to remember the time a movie starts, recognize when clothing needs to be washed, and pay their bills on time without another adult reminding them.

So, that begs the question: what counts as independence? We live in a time in which means we have a plethora of tools at our fingertips that weren’t available even a few years ago. Here are a few things you might want to think about in terms of independence:

- What are the individual’s peers doing? Is it common for their peers to use a technological tool such as an iPad in the behavior you’re targeting? If not what are they using? Would that be an option for your learner?

- What do you use in your day? If I’m using a Reminders app to keep track of my grocery list, then there’s no reason an individual with autism shouldn’t be allowed to do the same!

- What does the research say? Many of the technological tools we use haven’t been out for very long, so it’s only been in the past couple of years that the research base is starting to catch up in terms of appropriate use of tablets, smartphones, and the like. But there’s a lot of good research out there! Take a look at the suggested reading list at the end of this article (and don’t forget to look at the reference lists in those articles to find more research.)

- What does the individual gravitate towards? I have some students who prefer paper and pencil, and others that enjoy using tablets. I’m going to select interventions and tools for independence based on the individual’s own preferences! This may mean you have to try a few things out before you find the best fit.

All in all, I think it’s essential that individuals with autism be held to the same standard as the neurotypical population, not a higher standard when it comes to teaching independence.

Suggested Readings:

de Joode, E., van Heugten, C., Verhey, F., & van Boxtel, M. (2010). Efficacy and usability of assistive technology for patients with cognitive deficits: A systematic review. Clinical rehabilitation, 24(8), 701-714.

Hill, D. A., Belcher, L., Brigman, H. E., Renner, S., & Stephens, B. (2013). The Apple iPad (TM) as an Innovative Employment Support for Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Other Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 44(1), 28.

Kagohara, D. M., Sigafoos, J., Achmadi, D., O’Reilly, M., & Lancioni, G. (2012). Teaching children with autism spectrum disorders to check the spelling of words. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 304-310.

Kagohara, D. M., van der Meer, L., Ramdoss, S., O’Reilly, M. F., Lancioni, G. E., Davis, T. N., Rispoli, M., Lang, R., Marschik, P. B., Sutherland, D., Green, V. A., & Sigafoos, J. (2013). Using iPods® and iPads® in teaching programs for individuals with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 147-156.

Mechling, L. C., Gast, D. L., & Seid, N. H. (2009). Using a personal digital assistant to increase independent task completion by students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1420-1434.

Uphold, N. M., Douglas, K. H., & Loseke, D. L. (2014). Effects of using an iPod app to manage recreation tasks. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 39(2), 88-98.

Van Laarhoven, T., Johnson, J. W., Van Laarhoven-Myers, T., Grider, K. L., & Grider, K. M. (2009). The effectiveness of using a video iPod as a prompting device in employment settings. Journal of Behavioral Education, 18(2), 119-141.

Wehmeyer, M. L., Palmer, S. B., Shogren, K., Williams-Diehm, K., & Soukup, J. H. (2010). Establishing a causal relationship between intervention to promote self- determination and enhanced student self-determination. The Journal of Special Education, 46(4), 195-210.

WRITTEN BY SAM BLANCO, MSED, BCBA

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-15 in NYC. Working in education for twelve years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam utilizes strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently a PhD candidate in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College. She is also an assistant professor in the ABA program at The Sage Colleges.

Pick of the Week: Save 20% on Daily Living Skills games!

Help your learner navigate their town, shop for groceries and tell time with these fun and educational games!

*Promotion is valid until July 10th 2017 at 11:59pm ET. Offer cannot be applied to previous purchases, combined with any other offers, transferred, refunded, or redeemed and/or exchanged for cash or credit. Different Roads to Learning reserves the right to change or cancel this promotion at any time. To redeem offer at differentroads.com, enter promo code

PLAY2017 at checkout.

Prompt Fading For Parents

This week, Leanne Page M.Ed, BCBA, offers advice on how to avoid prompt dependence.

This piece originally appeared on bsci21.org.

“Dear Behavior BFF, I am not a parent myself but am writing you about my nephew. My sister and brother in law are constantly telling him what to say. “Tell her thank you. Say good morning. Say I want to eat dinner now.” I rarely hear the kid saying anything other than the exact words he is told to say. Is this normal? It seems like a terrible idea to me.”

The principles of behavior analysis can be helpful to anyone, not just parents. What you are describing here is a high level of prompting that is likely leading to prompt dependence. The boy’s parents are giving so many prompts that he is not responding independently.

Is this normal? With parents – who knows?! We each do our own thing. We almost always start something with the purest of intentions as I’m sure your sister and brother in law have here. They want to help their son to speak, help him to participate in social interactions, and help him to learn to be respectful. But maybe they are helping too much.

It’s likely time for some prompt fading. When teaching new skills, it is common to start with high levels of prompting to help the learner practice success and receive positive reinforcement. But we can’t stay there forever. We have to fade out those prompts.

Other situations where parents are likely to over-prompt and be ready for some prompt fading strategies: toileting schedules and your child never initiates, always giving choices and never letting your child come up with a request independently, doing things hand over hand, doing daily living activities for your child, etc.

Step back one step on your prompts. Still provide a prompt, but scale it back a bit. Find where you are on this list and go down one.

- Full physical – hand over hand. Doing things FOR your child.

- Partial physical – still doing some parts hand over hand, but letting the child do some independently.

- Full verbal – telling them what to say as given in the original question above.

- Partial verbal – give part of the response, not the whole thing.

- Gestural – give a gesture or a cue

*This is not an exhaustive prompt hierarchy. There is more detail within behavior analysis but will stop here as parents are the intended audience and may not need that level of technicality.

Some ideas to fade out the full verbal prompt are to give an indirect or partial verbal prompt. From the examples you gave, instead, you could say:

“What do you say?”

“Do you need something?”

“Good ……”

Prompting your child can be a good thing, a great thing, even a research based thing. But when all you do all day is prompt- maybe it’s time to take a step back. Don’t drop the prompts all together. We still want to be sure the child is successful in each situation so they can gain reinforcement and see an increase of the desired behaviors in these situations.

Step back one prompting level at a time. When your child is successful at that level, step back again. Fade out the prompts until he is able to respond independently and the constant telling him what to say is a distant memory!

We barely scratched the surface on prompts and prompt fading. Here are some good places to start learning more about it!

Alberto, P. A., & Troutman, A. C. (2012). Applied behavior analysis for teachers. Pearson Higher Ed.

Cooper, J. (2009). 0., Heron, TE, & Heward, WL (2007). Applied behavior analysis.

MacDuff, G. S., Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (2001). Prompts and prompt-fading strategies for people with autism. Making a difference: Behavioral intervention for autism, 37-50.

About The Author

Leanne Page, MEd, BCBA, is the author of Parenting with Science: Behavior Analysis Saves Mom’s Sanity. As a Behavior Analyst and a mom of two little girls, she wanted to share behavior analysis with a population who could really use it- parents!

Leanne’s writing can be found in Parenting with Science and Parenting with ABA as well as a few other sites. She is a monthly contributor to bSci21.com , guest host for the Dr. Kim Live show, and has contributed to other websites as well.

Leanne has worked with children with disabilities for over 10 years. She earned both her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from Texas A&M University. She also completed ABA coursework through the University of North Texas before earning her BCBA certification in 2011. Leanne has worked as a special educator of both elementary and high school self-contained, inclusion, general education, and resource settings.

Leanne also has managed a center providing ABA services to children in 1:1 and small group settings. She has extensive experience in school and teacher training, therapist training, parent training, and providing direct services to children and families in a center-based or in-home therapy setting.

Leanne is now located in Dallas, Texas and is available for: distance BCBA and BCaBA supervision, parent training, speaking opportunities, and consultation. She can be reached via Facebook or at Lpagebcba@gmail.com.

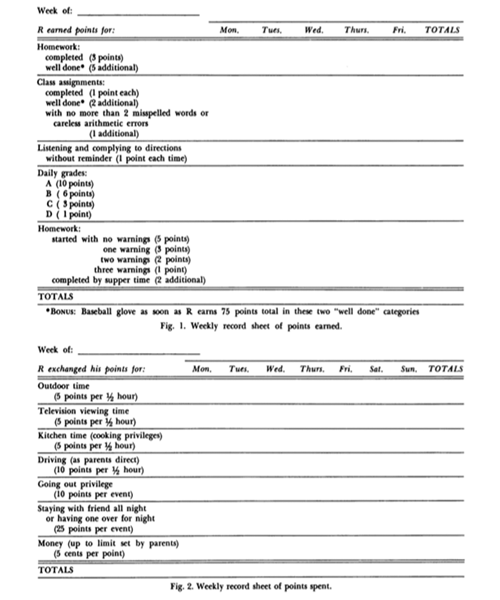

Using Contingency Contracts in the Classroom

As adults, we’re fairly accustomed to contracts for car loans, new employment, or updates to our smartphones. But contracts can also be beneficial in the classroom setting.

A contingency contract is defined as “a mutually agreed upon document between parties (e.g., parent and child) that specifies a contingent relationship between the completion of specified behavior(s) and access to specified reinforcer(s)” (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). There are several studies that indicate using a contingency classroom can be beneficial in the classroom setting.

Cantrell, Cantrell, Huddleston, & Wooldridge (1969) identified steps in creating contingency contracts:

(1) Interview the parent or guardian of the student. This allows you to work together to identify problem behaviors to be addressed, identify the contingencies currently maintaining these behaviors, determine the child’s current reinforcers, and establish what reinforcement or punishment procedures will be used.

(2) Use this information to create a clear, complete, and simple contract. The authors provide examples of how these contracts might look. You can vary the contract based upon the behaviors you are addressing with your student and the student’s ability to comprehend such contracts.

(3) Build data collection into the contract itself. You can see an example from the article below. For this example, it is clear how points are earned and how the child can utilize those points, and the contract itself is a record of both the points and the child’s behaviors.

There are clear benefits to utilizing such contingency contracting: building relationships across different environments in which the student lives and works, addressing one or more challenging behaviors simultaneously, and providing opportunities for students to come into contact with reinforcement. You can read the entire article here:

Cantrell, R. P., Cantrell, M. L., Huddleston, C. M., & Wooldridge, R. L. (1969). Contingency contracting with school problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 2(3), 215-220.

And much more has been written about contingency contracting. If you’d like to learn more, we suggest taking a look at one or more of the following:

Bailey, J. S., Wolf, M. M., & Phillips, E. L. (1970). Home-based reinforcement and the modification of pre-delinquent’s classroom behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 3(3), 223-233.

Barth, R. (1979). Home-based reinforcement of school behavior: A review and analysis. Review of Educational Research, 49(3), 436-458.

Broughton, S. F., Barton, E. S., & Owen, P. R. (1981). Home based contingency systems for school problems. School Psychology Review, 10(1), 26-36.

Miller, D. L., & Kelley, M. L. (1991). Interventions for improving homework performance: A critical review. School Psychology Quarterly, 6(3), 174.

WRITTEN BY SAM BLANCO, MSED, BCBA

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-15 in NYC. Working in education for twelve years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam utilizes strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently a PhD candidate in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College. She is also a lecturer in the ABA program at The Sage Colleges.

Pick of the Week: Save 20% on select speech and language workbooks!

These books are perfect for helping young learners strengthen their communications skills!