This week, Leanne Page M.Ed, BCBA, offers advice on how to avoid prompt dependence.

This piece originally appeared on bsci21.org.

“Dear Behavior BFF, I am not a parent myself but am writing you about my nephew. My sister and brother in law are constantly telling him what to say. “Tell her thank you. Say good morning. Say I want to eat dinner now.” I rarely hear the kid saying anything other than the exact words he is told to say. Is this normal? It seems like a terrible idea to me.”

The principles of behavior analysis can be helpful to anyone, not just parents. What you are describing here is a high level of prompting that is likely leading to prompt dependence. The boy’s parents are giving so many prompts that he is not responding independently.

Is this normal? With parents – who knows?! We each do our own thing. We almost always start something with the purest of intentions as I’m sure your sister and brother in law have here. They want to help their son to speak, help him to participate in social interactions, and help him to learn to be respectful. But maybe they are helping too much.

It’s likely time for some prompt fading. When teaching new skills, it is common to start with high levels of prompting to help the learner practice success and receive positive reinforcement. But we can’t stay there forever. We have to fade out those prompts.

Other situations where parents are likely to over-prompt and be ready for some prompt fading strategies: toileting schedules and your child never initiates, always giving choices and never letting your child come up with a request independently, doing things hand over hand, doing daily living activities for your child, etc.

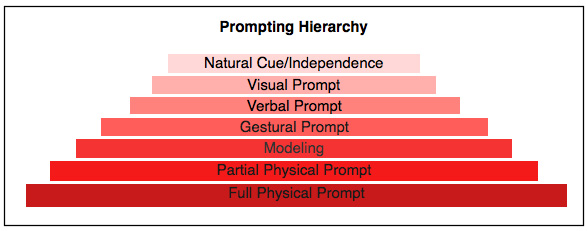

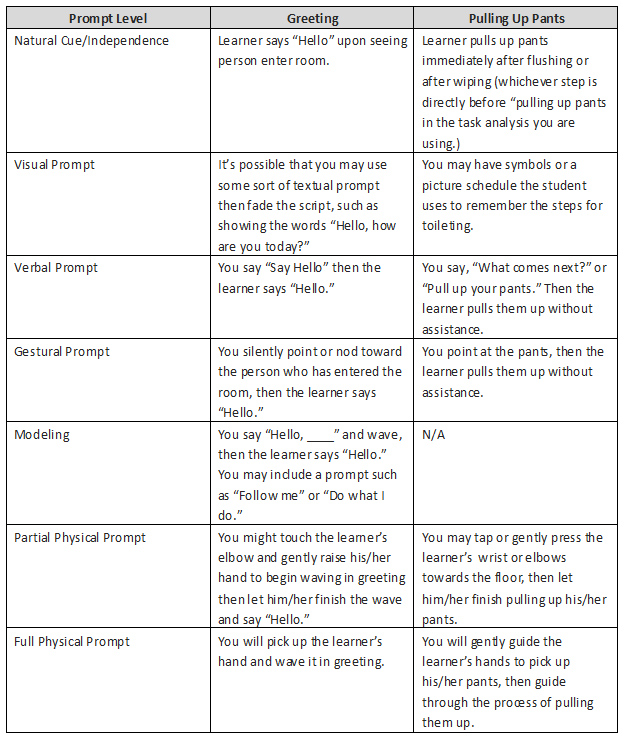

Step back one step on your prompts. Still provide a prompt, but scale it back a bit. Find where you are on this list and go down one.

- Full physical – hand over hand. Doing things FOR your child.

- Partial physical – still doing some parts hand over hand, but letting the child do some independently.

- Full verbal – telling them what to say as given in the original question above.

- Partial verbal – give part of the response, not the whole thing.

- Gestural – give a gesture or a cue

*This is not an exhaustive prompt hierarchy. There is more detail within behavior analysis but will stop here as parents are the intended audience and may not need that level of technicality.

Some ideas to fade out the full verbal prompt are to give an indirect or partial verbal prompt. From the examples you gave, instead, you could say:

“What do you say?”

“Do you need something?”

“Good ……”

Prompting your child can be a good thing, a great thing, even a research based thing. But when all you do all day is prompt- maybe it’s time to take a step back. Don’t drop the prompts all together. We still want to be sure the child is successful in each situation so they can gain reinforcement and see an increase of the desired behaviors in these situations.

Step back one prompting level at a time. When your child is successful at that level, step back again. Fade out the prompts until he is able to respond independently and the constant telling him what to say is a distant memory!

We barely scratched the surface on prompts and prompt fading. Here are some good places to start learning more about it!

Alberto, P. A., & Troutman, A. C. (2012). Applied behavior analysis for teachers. Pearson Higher Ed.

Cooper, J. (2009). 0., Heron, TE, & Heward, WL (2007). Applied behavior analysis.

MacDuff, G. S., Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (2001). Prompts and prompt-fading strategies for people with autism. Making a difference: Behavioral intervention for autism, 37-50.

About The Author

Leanne Page, MEd, BCBA, is the author of Parenting with Science: Behavior Analysis Saves Mom’s Sanity. As a Behavior Analyst and a mom of two little girls, she wanted to share behavior analysis with a population who could really use it- parents!

Leanne’s writing can be found in Parenting with Science and Parenting with ABA as well as a few other sites. She is a monthly contributor to bSci21.com , guest host for the Dr. Kim Live show, and has contributed to other websites as well.

Leanne has worked with children with disabilities for over 10 years. She earned both her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from Texas A&M University. She also completed ABA coursework through the University of North Texas before earning her BCBA certification in 2011. Leanne has worked as a special educator of both elementary and high school self-contained, inclusion, general education, and resource settings.

Leanne also has managed a center providing ABA services to children in 1:1 and small group settings. She has extensive experience in school and teacher training, therapist training, parent training, and providing direct services to children and families in a center-based or in-home therapy setting.

Leanne is now located in Dallas, Texas and is available for: distance BCBA and BCaBA supervision, parent training, speaking opportunities, and consultation. She can be reached via Facebook or at Lpagebcba@gmail.com.