In this month’s ASAT feature, Maithri Sivaraman and Ruth Donlin offer advice on selecting the best games for children with ASD. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook!

My son is 5 years old and was diagnosed with autism when he was two. He has responded well to early intervention services in terms of his communication and daily living activities. But it is still challenging to for him to play games with his neurotypical peers. When all the kids at a birthday party are playing “Simon Says,” my son prefers to play alone with his toys or just watch the other kids playing. I don’t know how to teach him to play new games or even identify what kind of games he likes. Could you provide some suggestions?

The growing awareness about the early signs of ASD has made it possible for an increasing number of children to be diagnosed by the age of 3 years (Stahmer, 2011). Considering the difficulty in building social relationships and peer play that is often associated with ASD it is important that specific instruction on social behaviors in various play situations is provided. Research has shown that extensive and planned interaction with peers facilitates social skill development (e.g., Krantz & Mclannahan, 1993; Baker, Koegel & Koegel, 1998). At your son’s age, this interaction primarily occurs during play.

Play has been described as a “child’s workshop” where social rules and consequences are explored (Bruner, 1975). Teaching a game to a child has consequences beyond the game itself: Apart from having fun, it could lead to social engagement, formation of friendships and create abundant opportunities for imitation, negotiation, cooperation, and other skills. However, though important, teaching games to children with autism often involves many challenges, such as the play activity not being motivating to the child, the need for intrusive prompting, having to teach the rules of each game, and managing problem behavior, to name a few. Some of these challenges can be overcome by using the strategies described below.

Considerations When Choosing a Game

Choose a game that is a match to the child’s developmental level and one that incorporates his or her interests and facilitates social skill development. Games may provide an appropriate social context to the perseverative interests of children with ASD (Koegel et al., 2012; Baker, Koegel & Koegel, 1998). It is a great idea to modify games to accommodate the child’s interests. For example, if the child has a keen interest in vehicles, the Red Light/Green Light game can be modified to be played with cars rather than people. A perseverative interest with names of washing machine brands can be accommodated in the same game by asking the child to take a step forward each time one brand name is said or stop when a different brand is said. For a child who likes twirling threads, the thread could be at the finish line to motivate the child to “go” during Red Light/Green Light.

Strategies for Teaching Games

Children with ASD are less likely to learn age-appropriate play skills through mere exposure to play materials and peers using those materials. Instead, intervention is often required to teach appropriate play skills directly and explicitly to these children (Lifter, Mason & Barton, 2012; Malone and Langone, 1999). When planning for social interactions and game play with others, the child with autism should understand what to do before being placed in the social play situation and have appropriate supports to avoid failed social experiences that could decrease long-term interest in the activity. Some strategies for teaching games follow.

- Modeling – Provide your son with opportunities to observe others playing the game. At this stage, the only expectation is that the child stays within the play area for a few minutes and observes others. No other form of participation/engagement is required. Alternatively, providing a video model of a group playing the same game will serve as a form of priming and prepare the child for the actual experience, as long as the child has learned and is competent with observing of others, in vivo or video.

- Shaping – The child could initially engage only in those play actions (relevant to the game) that he can do independently. Subsequently, better performances in these actions can be modeled and expected (Ward, 2011). For example, in a game like Red Light/Green Light, your son may initially just run along with all the other players. It does not matter that he does not stop at the Red Light. But if he/she is successful at this level and shows independent participation, over the course of the next few instances, a play partner could be made to hold hands with your son and have him stop at the Red Light. Gradually, the partner could stop holding hands and independent performance in “red” and “green” can be tested. Prompting – After being given a few opportunities to observe others playing the game, some prompting might be required for the child to improve existing play behaviors. In a least-to-most (LTM) prompting hierarchy, the least intrusive prompts are provided first. More intrusive prompts are provided only if the expected behavior does not occur at the present level of prompting. For example, in the Red light/Green light game, if a child does not start running when the leader says “green,” the teacher might initially say, “What should you do now?” A gesture to move or a gentle push may be provided if the student does not respond to the teacher’s question. One LTM prompt hierarchy that is often used to teach these kinds of skills is indirect verbal, direct verbal, gestural and a physical prompt, in order of increasing intrusiveness (Cooper, Heron & Heward, 2007; Davis-Temple, Jung & Sainato, 2014; Libby, Weiss, Bancroft & Ahearn, 2008). For example, when the leader says green, an indirect verbal prompt could be “What should you do now?” while a direct verbal prompt would be saying, “Run.” An example of gestural prompt for this situation would be a hand gesture indicating the child to move in a certain direction whereas a physical prompt would be to hold the child’s arm and gently push him forward. In contrast, A most-to-least (MTL) prompting hierarchy involves providing the most intrusive prompt initially. The prompt is then faded gradually to facilitate independent performance. Using the previous example, an MTL prompt strategy would begin first with a physical prompt and then fade to a gestural prompt, direct verbal, indirect verbal prompt, and finally allow for independence as the child is successful. The prompting techniques used should be tailored to each learner. Because LTM prompting allows the child to attempt the skill independently first, MTL prompting is recommended if errors (which can be more common with LTM) have been found to impede the child’s learning. LTM can be used for children who show rapid acquisition of skills and are familiar with this prompting strategy (Libby, Weiss, Bancroft & Ahearn, 2008).

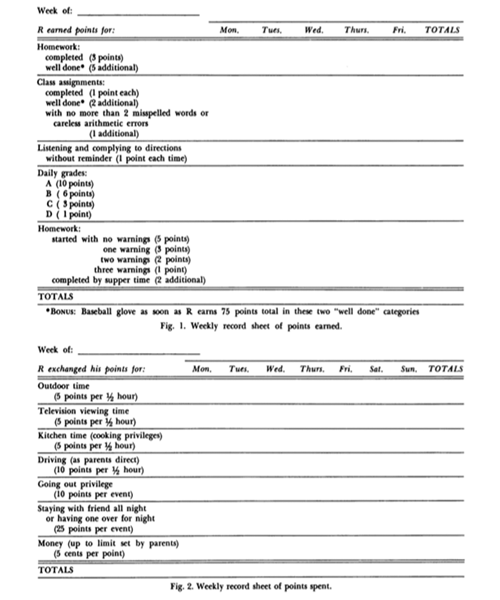

- Positive Reinforcement – Try to use naturally occurring reinforcers as much as possible. Exaggeration of facial expressions and emotions, and making funny noises could be a part of the game itself to make the activity more enjoyable. For instance, stopping during the Red Light could be accompanied by exaggerated body postures and funny facial expressions. Also, if the child is familiar with a token system, it could be extended to the game as a “points table” where everyone’s scores in the game are recorded. The winner of the game might then be given a chance to choose the next activity. Reinforcers that are a natural result of play are recommended over edibles/tangible items because they can be easily transferred to the natural environment during play with typically developing peers (Stokes & Baer, 1977). Maximizing the use of activities within the game that can serve as reinforcers will promote generalization. Learning to play a game in one situation and being able to do it flexibly in other similar but different situations requires the events within the game (stopping at “Red Light” with a screeching sound like a car, jumping and saying “Woohoo” at the finish line) to serve as reinforcers as opposed to using edible or tangible items which may not be available everywhere.

- Chaining – In the context of simple games with a consistent, predictable sequence of play such as “Hi-Ho-Cherry-O” or “Candy Land”, the game could be broken down into a series of simple steps (task analysis). Teaching one step at a time to mastery before introducing the other steps could simplify the game for the child. For instance, in the game Candy Land, your son might initially be required only to pick up the card and label the color, while the parent or teacher helps him complete all the additional steps on his turn (e.g., finding his piece and moving it to the corresponding color). Following success at this step, he could be expected to pick up the card, label the color and also move his piece on the board. Subsequently, telling a peer to take a turn, waiting appropriately for his turn, setting up the game and cleaning up could be added to the list of expected behaviors.

- Scripting – Playing games provides numerous opportunities to develop or increase communication skills such as imitating words, making comments (“This is fun,” “Your turn”), making requests (“Help”) and initiating communication (“Let’s play”). Visual script interventions have been shown to be effective with children with autism, including those with minimal language (e.g., single spoken words, Krantz & McClannahan, 1998) and those with extensive verbal skills but poor social skills (Krantz & McClannahan, 1993). Scripts typically are a written or pictorial appropriate phrases or sentences presented during play to evoke responding. For example, a script during the Red Light/Green Light game can serve as a prompt for social greetings (“Hi, let’s play”), asking for a turn (“My turn to be the leader”) and making comments (“We’ve all stopped like statues!”).

Assessing motivation – How to tell if the child is interested?

Gauging child motivation for an activity is as important as knowing how to teach a game. Being indifferent to a child’s interest level and focusing only on the process can impede his/her ability to play games (Taylor et al., 2005). The overwhelming urge to teach the child to play by all the rules of the game on the very first opportunity can be truly aversive for the child (and the parent or teacher!) and lead to problem behavior. A closer observation might reveal that problem behavior occurs when the child’s interest in the game starts to wane and continued engagement is expected.

This challenge can be overcome by taking motivation into consideration and choosing games that have components which you know the child enjoys. This increases the likelihood that the learner will exhibit independence in at least one of the expected play behaviors during the game. The Red Light/Green Light game might work well for children who like to run or be outdoors; Simon Says might work for children who have a good imitation repertoire; Hangman may be motivating for children who like letters; and simple board games like Tummy Ache/Pizza Pizza (Orchard Toys) may be enjoyed by children who prefer visual stimuli and matching.

Additionally, here are some ways of measuring motivation during the game (Ward, 2011).

- Mands/Requests – Did the child request for the game after a few exposures? Did he/she ask for a turn to hold up the colored cards and say “red” and “green”?

- Initiations – did he/she make any initiations during the game? (e.g., asking a partner to “stop” when they didn’t)

- Responses to partner initiations – does the child respond to play partners? (e.g., moving forward when a partner asks him to do so)

- Affect – Does the child seem happy? Is he/she smiling, jumping, or laughing?

- Independent play actions – Does the child run by him/herself during “green”? Or go back to the starting line at the end of one round?

If the game has been broken down into doable steps with appropriate reinforcement and the child is still not initiating or displaying independent play actions, these are clear indications of low motivation in the game, which can be also due to task difficulty. If such situations persist, it is best to choose a different game. Identifying a child’s disinterest and knowing when to stop, or modifying a game in a manner that might enhance motivation, can facilitate success. Motivation can be fleeting: what was fun yesterday might not be fun today. But being proactive about gauging these variations is what should be lasting.

Summary

We have learned many effective ways to teach games over the years (Jung, 2013; Krantz & McClannahan, 1998; Maurice, Green & Luce, 1996; Stahmer & Schreibman, 1992). Since playing games is an important activity among typically developing children, play activities serve as an opportunity for children with ASD to learn appropriate social behaviors (Davis-Temple, Jung & Sainato, 2014). Whatever the goals associated with each game, adding “having fun” as one of them, and identifying and monitoring observable measures of enjoyment, may be the key to successful game instruction. Being process-oriented and showing our kids that games can be fun is more important than playing the game the right way.

References

Baker, M.J., Koegel, R., & Koegel, L. (1998). Increasing the social behavior of young children with autism using their obsessive behaviors. The Journal of the Association of Persons with Severe Handicaps. 23, 300-308.

Bruner, J. (1975). From communication to language: A psychological perspective. Cognition. 3, 255-287.

Cooper, J.O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Davis-Temple, J., Jung, S., & Sainato, D. M. (2014). Teaching young children with special needs and their peers to play board games: Effects of a least to most prompting procedure to increase independent performance. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 7(1), 21–30.

Jung, S., & Sainato, D. M. (2013). Teaching play skills to children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 38(1), 74-90.

Koegel, R., Fredeen, R., Kim, S., Danial, J., Rubinstein, D., & Koegel, L. (2012). Using perseverative interests to improve interactions between adolescents with autism and their typical peers in school settings. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(3), 133–141.

Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1993). Teaching children with autism to initiate to peers: Effects of a script-fading procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(1), 121–132.

Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1998). Social interaction skills for children with autism: A script-fading procedure for beginning readers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(2), 191–202.

Libby, M. E., Weiss, J. S., Bancroft, S., & Ahearn, W. H. (2008). A comparison of most-to-least and least-to-most prompting on the acquisition of solitary play skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1(1), 37–43.

Lifter, K., Mason, E. J., & Barton E. E. (2012). Children’s play: Where we have been and where we could go. Journal of Early Intervention. 33,281–297.

Malone, D. M., & Langone, J. (1999). Teaching object-related play skills to preschool children with developmental concerns. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 46, 325-336.

Maurice, C., Green, G., & Luce, S.C. (1996). Behavioral intervention for young children with autism: A manual for parents and professionals. Austin, TX, US: PRO-ED.

Stahmer, A. C., Akshoomoff, N., & Cunningham, A. B. (2011). Inclusion for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: The first ten years of a community program. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 15(5), 625–641.

Stahmer, A. C., & Schreibman, L. (1992). Teaching children with autism appropriate play in unsupervised environments using a self-management treatment package. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25(2), 447–459.

Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10(2), 349–367.

Taylor, B.A., Hoch, H., Potter, B., Rodriguez, A., Spinnato, D., & Kalaigian, M. (2005). Manipulating establishing operations to promote initiations toward peers in children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 26, 385-392.

Ward, S. (2011). What you need to know about motivation and teaching games: An in-depth analysis. Lulu.

About The Authors

Maithri Sivaraman is a BCBA with a Masters in Psychology from the University of Madras and holds a Graduate Certificate in ABA from the University of North Texas. She currently runs ‘Tendrils Centre for Autism Research and Intervention’ which is a registered resource center providing behavior analytic services to families in Chennai, India, conducting workshops, and supervising students pursuing certification. She has presented papers at international conferences, published articles in peer-reviewed journals and has been authoring a column for the ‘Autism Network’, India’s quarterly autism journal. As an Extern at the Association for Science in Autism Treatment she has been involved in the international dissemination of evidence-based treatments writing articles for their newsletter and responding to media reports that highlight treatments for autism.

Ruth Donlin, M.S., is a Board Member of ASAT since 2010 and on the Public Relations Committee. She is a consultant in private practice based in New York, and has provided consultation to schools, agencies, and home programs for children and adults on the autism spectrum for 20 years. She presents on a variety of topics such as managing challenging behaviors, using visual supports, team dynamics, and social skill development at conferences regionally, nationally, and internationally. Ruth is Past-President of the Autism Special Interest Group (SIG) of the Association of Behavior Analysis International.