The safety of individuals with autism is an enormous concern for parents and caregivers across the country. POAC Autism Services consulted with Dennis Debbaudt to pioneer The Autism Shield Program providing safety training for police, fire fighters, and EMTs. More recently, POAC has developed a companion workshop designed for caregivers, teachers, and child study team members.

Sam had a chance to talk with Gary Weitzen, Executive Director of POAC Autism Services. Gary is an excellent source of information and has been incredibly generous and proactive in sharing his experiences and knowledge with the community. POAC has now trained more than 15,000 police officers and first responders on autism recognition and safety. We’re sure you will find Gary’s insight and suggestions exceedingly helpful and applicable to children and adults of all ages.

***

Fifteen years ago, Gary Weitzen’s five-year-old son with autism went missing. The first place his parents looked was the lake, because like many children with autism, they knew he was drawn to water. Fortunate to find him in time to save him, this experience and many similar stories Gary would hear over the years, were the impetus for creating the Autism Shield Program. Gary is now the Executive Director at POAC, an organization in New Jersey that provides free resources for the autism community.

“The Autism Shield Program is a comprehensive program really designed to keep our children safe in their schools, homes, and communities,” Gary said. “It originally started training police officers. Multiple FBI studies have shown that if you have autism or any other developmental disability you’re seven times more likely to encounter police than if you don’t have autism. We’ve expanded it to the current program which also includes firefighters, EMTs, emergency first responders, school nurses, prison guards, and parents.”

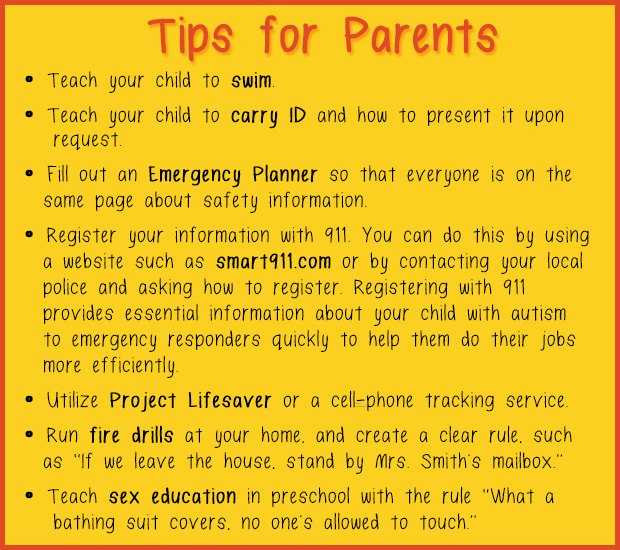

One thing that Gary stresses repeatedly is the need for children with autism to learn how to swim.

“I lived with the fact that my son almost drowned. [Fifteen years ago] it was just huge numbers of children with autism drowning. Like every week another child with autism died, another child with autism died. It was overwhelming,” Gary said. “We thought, we have to do something here. We have to let parents and police know exactly what’s going on here.”

Eight years ago, POAC started training police departments on how to respond to emergency situations that involved individuals with autism.

“I always tell the first responders the same thing: individuals with autism are never lost. Ever. They’re always going somewhere. They didn’t wander out of the house like someone with Alzheimer’s would or even a small child would. Our guys are going somewhere so you want to try to get the information right away about where you think they might be going from the caregiver. If you get that information beforehand, you can try to search there. Always start a search with bodies of water. Always. If the child is missing from a specific location, start with concentric circles out and hit every body of water,” Gary said.

Two more suggestions have been extremely beneficial for law enforcement and first responders in dealing effectively with individuals with autism. The first is to speak in short, direct sentences telling the individual what TO DO instead of what NOT to do. The second is to provide a prompt if the individual is without identification and not giving contact information upon request.

“Let’s say, you ask Charlie his phone number, he doesn’t give you a phone number. Ask his phone number again, but this time prompt it with the area code for that area. ‘Charlie, what’s your phone number, 9-7-3…’ Ninety-nine times out of 100 our guys with autism will finish their phone number.”

Gary also suggests families complete an Emergency Planner and to register with 911 in order to assist with improving safety and emergency response efforts. He urges families to utilize services such as Project Lifesaver.

“[Project Lifesaver] has been in existence for over 15 years. It’s LoJack for our kids who wander off. It was designed for Alzheimer’s patients and expanded to individuals with autism. There are now more individuals with autism that are on it than people with Alzheimer’s,” Gary said. “The success rate in 15 years nationwide: 100%. There’s never been a case of an individual on the program not being found alive ever, ever, ever. Hundred percent success rate. And the average time it takes from the time mom calls up ‘My child is missing’ until the sheriff’s officer has their child in their hands: 14 minutes.”

For individuals who may not tolerate the Project Lifesaver bracelet, Gary recommends creating a rule about cell phones and using the cell phone to ensure the individual is safe.

“If the rule is I always have to have my smartphone with me, in my pants pocket, guess what, they will always have that smartphone with them in their pants pocket. And it doesn’t have to be turned on,” Gary said. “It just has to have power and with iPhones and Androids you can get free apps like the Find My iPhone. There’s also programs out there with Verizon, AT&T, and other providers for $10 a month to put a family locator on the phone, set up a location, so if the phone moves 50 feet away from wherever the location, work, school, home, mom or dad gets a text instantly. The phone is on the move. And you can track it in real time. So there are so many things that are out there that people need to take advantage of and could take advantage of. They just have to be told about them.”

Beyond wandering and encounters with police, POAC also works with fire departments and with parents to increase safety during house fires.

“Very often, individuals with Asperger’s will hide in a house fire. And look, regardless of their age—face it—our guys and girls will re-enter a burning building. This happens all the time. All the time, firefighters come, they save the child, the child’s with mom, with other kids, and in the confusion of the fire, especially if there’s somebody still in the house they’re trying to save, we’ve had so many individuals with autism walk right back into the burning house in front of the police, firefighters, and their family and burn alive and die in the house.”

Gary recommends running fire drills at home with clear rules, such as, “Stand by Mrs. Smith’s mailbox.” It’s also important to identify who will be responsible for the individual with autism during an emergency. But Gary cautions that even with supervision, an individual with autism may be dangerously insistent about re-entering a burning building.

“So, where’s the best place to put a child at the scene of a house fire? Locked in the back of a police car. They’ll potentially scream, bang their head, maybe hurt themselves, but they’re alive. They’re alive,” Gary said. “We have videos of a child wandering off and the firefighter actually trying to hold them and the kid just runs across the street back toward the building.”

POAC has also provided many trainings for both parents and professionals about sexual education for individuals with autism. Gary describes sexual abuse as a major problem for individuals with developmental disabilities that people are afraid to address.

“Unfortunately, the sexual abuse rate with our guys to sexual predators is through the roof. The numbers for females are, close to 70% of females with autism were sexually assaulted by predators. Seventy percent. Seven out of ten of our girls are sexually assaulted before age 18. And the number’s around 40% for males. And I go into why that is, they’re the perfect victim. They don’t understand intent, they don’t understand the social rules.”

“You have to start sexual education with our guys in preschool,” Gary said. “That shocks people when I say that, but Sex Ed in preschool is, ‘What a bathing suit covers no one’s allowed to touch.’ That’s Sex Ed in preschool. So it’s not as scary as people think. But you know when most Sex Ed is taught to individuals with developmental disabilities? After something happens. After someone gets assaulted or after someone masturbated in class or someone touched someone inappropriately. You know, we better do something! No, they’re fifteen! Start early.”

“A big problem for parents of children with autism, and I say this as a parent of a child with autism, is that you’re thinking it’s not your kid. Parents on the lower end of the scale always think, ‘Nothing’s ever going to happen to my child because somebody’s always with them—it’s them kids with Asperger’s who are running willy-nilly off by themselves all the time—those are the ones getting into trouble.’ And then right across the room, the parents with the higher functioning kids think, ‘Well nothing’s ever going to happen to my son because my son tells me everything, it’s those low-functioning kids who can’t speak that everything’s happening to.’ But, it’s happening to all of our kids equally, wherever they fall on the spectrum, and the problem is the parents always think ‘Well, not my kid, it’s somebody else’s.’ No, you’ve got to think, this definitely could be my child so what do I have to do to increase his safety?”

POAC continues to provide free workshops and resources to residents in New Jersey. And Gary will continue with that effort for a long time yet. “I always joke that the Irish in me wants stuff to be meat and potatoes. I want it to be real. I want it to be real for the families. I want it to be real for the officers. Any one of our trainings, I want the person to walk away with something that they can use that day to make a child safer.”

If this story has touched you or you feel you can use it, Gary asks that you please consider making a tax-deductible donation to POAC.

Consider how you use scanning in your own life: searching a row of books on a shelf to find a particular title, trying to find your favorite tomato soup in a supermarket aisle filled with soups, or looking through a box of Legos for one blue square Lego to complete a structure. None of the ways we scan in the natural environment present materials in a field of 3 neatly lined-up items.

Consider how you use scanning in your own life: searching a row of books on a shelf to find a particular title, trying to find your favorite tomato soup in a supermarket aisle filled with soups, or looking through a box of Legos for one blue square Lego to complete a structure. None of the ways we scan in the natural environment present materials in a field of 3 neatly lined-up items. Always Be Pairing

Always Be Pairing As the first comprehensive, empirically tested intervention specifically designed for toddlers and preschoolers with autism, the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) is an early intervention approach for toddlers ages 12-36 months and continuing until ages 48-60 months. The model does not require a particular setting for implementation and can be used by parents, teachers, therapists, at home, in preschool or in a clinical setting. To help you get started with this early intervention model developed by Sally Rogers, Ph.D., and Geraldine Dawson, Ph.D., we are offering a 15% discount on the

As the first comprehensive, empirically tested intervention specifically designed for toddlers and preschoolers with autism, the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) is an early intervention approach for toddlers ages 12-36 months and continuing until ages 48-60 months. The model does not require a particular setting for implementation and can be used by parents, teachers, therapists, at home, in preschool or in a clinical setting. To help you get started with this early intervention model developed by Sally Rogers, Ph.D., and Geraldine Dawson, Ph.D., we are offering a 15% discount on the

Age level: Preschool, Early Elementary

Age level: Preschool, Early Elementary.gif)

Remember, this week only, take 15% off your order of the

Remember, this week only, take 15% off your order of the