Help young learners recognize size, color, patterns and logic!

In working with individuals with autism, my goal is always to help them move towards independence. Recently, I was speaking with a colleague about an intervention I had done in which a child independently began his bedtime routine (brushing teeth, changing into pajamas, etc.) when his VibraLite watch vibrated at 8PM. When the watch vibrates, he resets it for 8PM the next day. Her response was that she didn’t believe that was truly independent behavior, since he required the prompt of the watch vibration. Many of you reading may agree with my colleague, but I think we must consider independence today in the context of our own behavior.

In the evening, I set an alarm clock, and I only wake up in the morning when it buzzes. When I run out of milk, I’ll put an alert in my Reminders app on my phone. When a friend invites me to lunch, I immediately enter the date in my calendar. All of these are technically examples of prompts, but if I am managing the prompts, I would argue that I am in fact engaging in independent behavior.

When I think about independent behavior, I want the children I work with to one day be able to grocery shop, go to work, eat a meal with a sibling, and more without having another adult facilitate those interactions. I want them to remember the time a movie starts, recognize when clothing needs to be washed, and pay their bills on time without another adult reminding them.

So, that begs the question: what counts as independence? We live in a time in which means we have a plethora of tools at our fingertips that weren’t available even a few years ago. Here are a few things you might want to think about in terms of independence:

All in all, I think it’s essential that individuals with autism be held to the same standard as the neurotypical population, not a higher standard when it comes to teaching independence.

Suggested Readings:

de Joode, E., van Heugten, C., Verhey, F., & van Boxtel, M. (2010). Efficacy and usability of assistive technology for patients with cognitive deficits: A systematic review. Clinical rehabilitation, 24(8), 701-714.

Hill, D. A., Belcher, L., Brigman, H. E., Renner, S., & Stephens, B. (2013). The Apple iPad (TM) as an Innovative Employment Support for Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Other Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 44(1), 28.

Kagohara, D. M., Sigafoos, J., Achmadi, D., O’Reilly, M., & Lancioni, G. (2012). Teaching children with autism spectrum disorders to check the spelling of words. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 304-310.

Kagohara, D. M., van der Meer, L., Ramdoss, S., O’Reilly, M. F., Lancioni, G. E., Davis, T. N., Rispoli, M., Lang, R., Marschik, P. B., Sutherland, D., Green, V. A., & Sigafoos, J. (2013). Using iPods® and iPads® in teaching programs for individuals with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 147-156.

Mechling, L. C., Gast, D. L., & Seid, N. H. (2009). Using a personal digital assistant to increase independent task completion by students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1420-1434.

Uphold, N. M., Douglas, K. H., & Loseke, D. L. (2014). Effects of using an iPod app to manage recreation tasks. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 39(2), 88-98.

Van Laarhoven, T., Johnson, J. W., Van Laarhoven-Myers, T., Grider, K. L., & Grider, K. M. (2009). The effectiveness of using a video iPod as a prompting device in employment settings. Journal of Behavioral Education, 18(2), 119-141.

Wehmeyer, M. L., Palmer, S. B., Shogren, K., Williams-Diehm, K., & Soukup, J. H. (2010). Establishing a causal relationship between intervention to promote self- determination and enhanced student self-determination. The Journal of Special Education, 46(4), 195-210.

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-15 in NYC. Working in education for twelve years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam utilizes strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently a PhD candidate in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College. She is also an assistant professor in the ABA program at The Sage Colleges.

Help your learner navigate their town, shop for groceries and tell time with these fun and educational games!

This week, Leanne Page M.Ed, BCBA, offers advice on how to avoid prompt dependence.

This piece originally appeared on bsci21.org.

“Dear Behavior BFF, I am not a parent myself but am writing you about my nephew. My sister and brother in law are constantly telling him what to say. “Tell her thank you. Say good morning. Say I want to eat dinner now.” I rarely hear the kid saying anything other than the exact words he is told to say. Is this normal? It seems like a terrible idea to me.”

The principles of behavior analysis can be helpful to anyone, not just parents. What you are describing here is a high level of prompting that is likely leading to prompt dependence. The boy’s parents are giving so many prompts that he is not responding independently.

Is this normal? With parents – who knows?! We each do our own thing. We almost always start something with the purest of intentions as I’m sure your sister and brother in law have here. They want to help their son to speak, help him to participate in social interactions, and help him to learn to be respectful. But maybe they are helping too much.

It’s likely time for some prompt fading. When teaching new skills, it is common to start with high levels of prompting to help the learner practice success and receive positive reinforcement. But we can’t stay there forever. We have to fade out those prompts.

Other situations where parents are likely to over-prompt and be ready for some prompt fading strategies: toileting schedules and your child never initiates, always giving choices and never letting your child come up with a request independently, doing things hand over hand, doing daily living activities for your child, etc.

Step back one step on your prompts. Still provide a prompt, but scale it back a bit. Find where you are on this list and go down one.

*This is not an exhaustive prompt hierarchy. There is more detail within behavior analysis but will stop here as parents are the intended audience and may not need that level of technicality.

Some ideas to fade out the full verbal prompt are to give an indirect or partial verbal prompt. From the examples you gave, instead, you could say:

“What do you say?”

“Do you need something?”

“Good ……”

Prompting your child can be a good thing, a great thing, even a research based thing. But when all you do all day is prompt- maybe it’s time to take a step back. Don’t drop the prompts all together. We still want to be sure the child is successful in each situation so they can gain reinforcement and see an increase of the desired behaviors in these situations.

Step back one prompting level at a time. When your child is successful at that level, step back again. Fade out the prompts until he is able to respond independently and the constant telling him what to say is a distant memory!

We barely scratched the surface on prompts and prompt fading. Here are some good places to start learning more about it!

Alberto, P. A., & Troutman, A. C. (2012). Applied behavior analysis for teachers. Pearson Higher Ed.

Cooper, J. (2009). 0., Heron, TE, & Heward, WL (2007). Applied behavior analysis.

MacDuff, G. S., Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (2001). Prompts and prompt-fading strategies for people with autism. Making a difference: Behavioral intervention for autism, 37-50.

About The Author

Leanne Page, MEd, BCBA, is the author of Parenting with Science: Behavior Analysis Saves Mom’s Sanity. As a Behavior Analyst and a mom of two little girls, she wanted to share behavior analysis with a population who could really use it- parents!

Leanne’s writing can be found in Parenting with Science and Parenting with ABA as well as a few other sites. She is a monthly contributor to bSci21.com , guest host for the Dr. Kim Live show, and has contributed to other websites as well.

Leanne has worked with children with disabilities for over 10 years. She earned both her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from Texas A&M University. She also completed ABA coursework through the University of North Texas before earning her BCBA certification in 2011. Leanne has worked as a special educator of both elementary and high school self-contained, inclusion, general education, and resource settings.

Leanne also has managed a center providing ABA services to children in 1:1 and small group settings. She has extensive experience in school and teacher training, therapist training, parent training, and providing direct services to children and families in a center-based or in-home therapy setting.

Leanne is now located in Dallas, Texas and is available for: distance BCBA and BCaBA supervision, parent training, speaking opportunities, and consultation. She can be reached via Facebook or at Lpagebcba@gmail.com.

Help young learners sharpen their critical thinking skills!

As adults, we’re fairly accustomed to contracts for car loans, new employment, or updates to our smartphones. But contracts can also be beneficial in the classroom setting.

A contingency contract is defined as “a mutually agreed upon document between parties (e.g., parent and child) that specifies a contingent relationship between the completion of specified behavior(s) and access to specified reinforcer(s)” (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). There are several studies that indicate using a contingency classroom can be beneficial in the classroom setting.

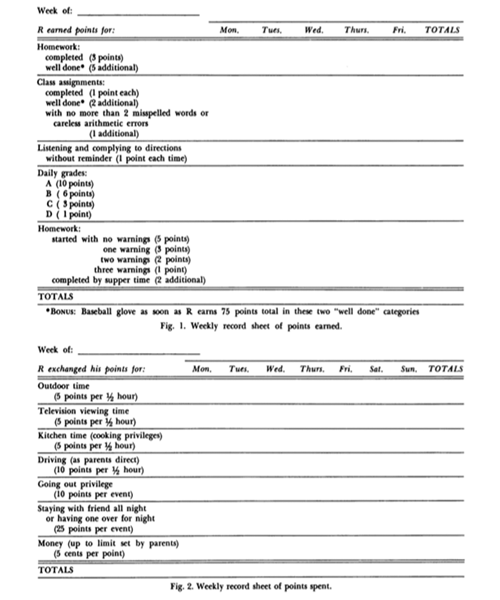

Cantrell, Cantrell, Huddleston, & Wooldridge (1969) identified steps in creating contingency contracts:

(1) Interview the parent or guardian of the student. This allows you to work together to identify problem behaviors to be addressed, identify the contingencies currently maintaining these behaviors, determine the child’s current reinforcers, and establish what reinforcement or punishment procedures will be used.

(2) Use this information to create a clear, complete, and simple contract. The authors provide examples of how these contracts might look. You can vary the contract based upon the behaviors you are addressing with your student and the student’s ability to comprehend such contracts.

(3) Build data collection into the contract itself. You can see an example from the article below. For this example, it is clear how points are earned and how the child can utilize those points, and the contract itself is a record of both the points and the child’s behaviors.

There are clear benefits to utilizing such contingency contracting: building relationships across different environments in which the student lives and works, addressing one or more challenging behaviors simultaneously, and providing opportunities for students to come into contact with reinforcement. You can read the entire article here:

Cantrell, R. P., Cantrell, M. L., Huddleston, C. M., & Wooldridge, R. L. (1969). Contingency contracting with school problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 2(3), 215-220.

And much more has been written about contingency contracting. If you’d like to learn more, we suggest taking a look at one or more of the following:

Bailey, J. S., Wolf, M. M., & Phillips, E. L. (1970). Home-based reinforcement and the modification of pre-delinquent’s classroom behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 3(3), 223-233.

Barth, R. (1979). Home-based reinforcement of school behavior: A review and analysis. Review of Educational Research, 49(3), 436-458.

Broughton, S. F., Barton, E. S., & Owen, P. R. (1981). Home based contingency systems for school problems. School Psychology Review, 10(1), 26-36.

Miller, D. L., & Kelley, M. L. (1991). Interventions for improving homework performance: A critical review. School Psychology Quarterly, 6(3), 174.

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-15 in NYC. Working in education for twelve years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam utilizes strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently a PhD candidate in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College. She is also a lecturer in the ABA program at The Sage Colleges.

In this month’s ASAT feature, Maithri Sivaraman and Ruth Donlin offer advice on selecting the best games for children with ASD. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook!

My son is 5 years old and was diagnosed with autism when he was two. He has responded well to early intervention services in terms of his communication and daily living activities. But it is still challenging to for him to play games with his neurotypical peers. When all the kids at a birthday party are playing “Simon Says,” my son prefers to play alone with his toys or just watch the other kids playing. I don’t know how to teach him to play new games or even identify what kind of games he likes. Could you provide some suggestions?

The growing awareness about the early signs of ASD has made it possible for an increasing number of children to be diagnosed by the age of 3 years (Stahmer, 2011). Considering the difficulty in building social relationships and peer play that is often associated with ASD it is important that specific instruction on social behaviors in various play situations is provided. Research has shown that extensive and planned interaction with peers facilitates social skill development (e.g., Krantz & Mclannahan, 1993; Baker, Koegel & Koegel, 1998). At your son’s age, this interaction primarily occurs during play.

Play has been described as a “child’s workshop” where social rules and consequences are explored (Bruner, 1975). Teaching a game to a child has consequences beyond the game itself: Apart from having fun, it could lead to social engagement, formation of friendships and create abundant opportunities for imitation, negotiation, cooperation, and other skills. However, though important, teaching games to children with autism often involves many challenges, such as the play activity not being motivating to the child, the need for intrusive prompting, having to teach the rules of each game, and managing problem behavior, to name a few. Some of these challenges can be overcome by using the strategies described below.

Considerations When Choosing a Game

Choose a game that is a match to the child’s developmental level and one that incorporates his or her interests and facilitates social skill development. Games may provide an appropriate social context to the perseverative interests of children with ASD (Koegel et al., 2012; Baker, Koegel & Koegel, 1998). It is a great idea to modify games to accommodate the child’s interests. For example, if the child has a keen interest in vehicles, the Red Light/Green Light game can be modified to be played with cars rather than people. A perseverative interest with names of washing machine brands can be accommodated in the same game by asking the child to take a step forward each time one brand name is said or stop when a different brand is said. For a child who likes twirling threads, the thread could be at the finish line to motivate the child to “go” during Red Light/Green Light.

Strategies for Teaching Games

Children with ASD are less likely to learn age-appropriate play skills through mere exposure to play materials and peers using those materials. Instead, intervention is often required to teach appropriate play skills directly and explicitly to these children (Lifter, Mason & Barton, 2012; Malone and Langone, 1999). When planning for social interactions and game play with others, the child with autism should understand what to do before being placed in the social play situation and have appropriate supports to avoid failed social experiences that could decrease long-term interest in the activity. Some strategies for teaching games follow.

Assessing motivation – How to tell if the child is interested?

Gauging child motivation for an activity is as important as knowing how to teach a game. Being indifferent to a child’s interest level and focusing only on the process can impede his/her ability to play games (Taylor et al., 2005). The overwhelming urge to teach the child to play by all the rules of the game on the very first opportunity can be truly aversive for the child (and the parent or teacher!) and lead to problem behavior. A closer observation might reveal that problem behavior occurs when the child’s interest in the game starts to wane and continued engagement is expected.

This challenge can be overcome by taking motivation into consideration and choosing games that have components which you know the child enjoys. This increases the likelihood that the learner will exhibit independence in at least one of the expected play behaviors during the game. The Red Light/Green Light game might work well for children who like to run or be outdoors; Simon Says might work for children who have a good imitation repertoire; Hangman may be motivating for children who like letters; and simple board games like Tummy Ache/Pizza Pizza (Orchard Toys) may be enjoyed by children who prefer visual stimuli and matching.

Additionally, here are some ways of measuring motivation during the game (Ward, 2011).

If the game has been broken down into doable steps with appropriate reinforcement and the child is still not initiating or displaying independent play actions, these are clear indications of low motivation in the game, which can be also due to task difficulty. If such situations persist, it is best to choose a different game. Identifying a child’s disinterest and knowing when to stop, or modifying a game in a manner that might enhance motivation, can facilitate success. Motivation can be fleeting: what was fun yesterday might not be fun today. But being proactive about gauging these variations is what should be lasting.

Summary

We have learned many effective ways to teach games over the years (Jung, 2013; Krantz & McClannahan, 1998; Maurice, Green & Luce, 1996; Stahmer & Schreibman, 1992). Since playing games is an important activity among typically developing children, play activities serve as an opportunity for children with ASD to learn appropriate social behaviors (Davis-Temple, Jung & Sainato, 2014). Whatever the goals associated with each game, adding “having fun” as one of them, and identifying and monitoring observable measures of enjoyment, may be the key to successful game instruction. Being process-oriented and showing our kids that games can be fun is more important than playing the game the right way.

References

Baker, M.J., Koegel, R., & Koegel, L. (1998). Increasing the social behavior of young children with autism using their obsessive behaviors. The Journal of the Association of Persons with Severe Handicaps. 23, 300-308.

Bruner, J. (1975). From communication to language: A psychological perspective. Cognition. 3, 255-287.

Cooper, J.O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Davis-Temple, J., Jung, S., & Sainato, D. M. (2014). Teaching young children with special needs and their peers to play board games: Effects of a least to most prompting procedure to increase independent performance. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 7(1), 21–30.

Jung, S., & Sainato, D. M. (2013). Teaching play skills to children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 38(1), 74-90.

Koegel, R., Fredeen, R., Kim, S., Danial, J., Rubinstein, D., & Koegel, L. (2012). Using perseverative interests to improve interactions between adolescents with autism and their typical peers in school settings. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(3), 133–141.

Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1993). Teaching children with autism to initiate to peers: Effects of a script-fading procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(1), 121–132.

Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1998). Social interaction skills for children with autism: A script-fading procedure for beginning readers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(2), 191–202.

Libby, M. E., Weiss, J. S., Bancroft, S., & Ahearn, W. H. (2008). A comparison of most-to-least and least-to-most prompting on the acquisition of solitary play skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1(1), 37–43.

Lifter, K., Mason, E. J., & Barton E. E. (2012). Children’s play: Where we have been and where we could go. Journal of Early Intervention. 33,281–297.

Malone, D. M., & Langone, J. (1999). Teaching object-related play skills to preschool children with developmental concerns. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 46, 325-336.

Maurice, C., Green, G., & Luce, S.C. (1996). Behavioral intervention for young children with autism: A manual for parents and professionals. Austin, TX, US: PRO-ED.

Stahmer, A. C., Akshoomoff, N., & Cunningham, A. B. (2011). Inclusion for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: The first ten years of a community program. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 15(5), 625–641.

Stahmer, A. C., & Schreibman, L. (1992). Teaching children with autism appropriate play in unsupervised environments using a self-management treatment package. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25(2), 447–459.

Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10(2), 349–367.

Taylor, B.A., Hoch, H., Potter, B., Rodriguez, A., Spinnato, D., & Kalaigian, M. (2005). Manipulating establishing operations to promote initiations toward peers in children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 26, 385-392.

Ward, S. (2011). What you need to know about motivation and teaching games: An in-depth analysis. Lulu.

About The Authors

Maithri Sivaraman is a BCBA with a Masters in Psychology from the University of Madras and holds a Graduate Certificate in ABA from the University of North Texas. She currently runs ‘Tendrils Centre for Autism Research and Intervention’ which is a registered resource center providing behavior analytic services to families in Chennai, India, conducting workshops, and supervising students pursuing certification. She has presented papers at international conferences, published articles in peer-reviewed journals and has been authoring a column for the ‘Autism Network’, India’s quarterly autism journal. As an Extern at the Association for Science in Autism Treatment she has been involved in the international dissemination of evidence-based treatments writing articles for their newsletter and responding to media reports that highlight treatments for autism.

Ruth Donlin, M.S., is a Board Member of ASAT since 2010 and on the Public Relations Committee. She is a consultant in private practice based in New York, and has provided consultation to schools, agencies, and home programs for children and adults on the autism spectrum for 20 years. She presents on a variety of topics such as managing challenging behaviors, using visual supports, team dynamics, and social skill development at conferences regionally, nationally, and internationally. Ruth is Past-President of the Autism Special Interest Group (SIG) of the Association of Behavior Analysis International.

Different Roads is proud to introduce you to Smart Kidz Club, a digital library of educational resources for young readers, available on web & mobile devices. Smart Kidz Club’s collection of more than 450 eBooks, interactive resources, play activities, and comprehension quizzes can be accessed safely off-line on mobile devices for anytime, anywhere learning. There’s even a special category dedicated to teaching children with ASD!

You can access a no-risk, two week free trial here!

This week, Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP shares her thoughts on the rising popularity of fidget spinners. This piece originally appeared on her blog at www.usevisualstrategies.com.

OK. . .so I got 5 fidget spinners for 5 grandchildren. Amazingly, there were 5 colors available so there would be no confusion over which spinner belonged to which child.

Then BAM. . .

School banned them!

No fidget spinners in school!

Well. . . .can you guess my immediate reaction?

Why not teach the students the correct way to use them? My logic says that would be a good goal. But obviously that school staff didn’t look at it with my logic.

Are fidget spinners a distraction or a learning tool?

I guess that depends on how you use them. It’s just like technology. Tech tools can be a huge helper for students or they can become an obsession for games and activities that cause students to hyper focus so they miss what’s important to pay attention to.

This is not just an autism thing. It’s also an ADHD thing. And a typically developing young child thing. Older kids, too. And don’t forget adults.

The internet has information

I’ve read a number of internet articles telling how wonderful fidget spinners are, but there seems to be more information about what’s bad. Here are examples.

But this complaint is most interesting

It’s written by young woman on the spectrum. She shares how students who need to stim in order to concentrate have endured years of training to have “Quiet Hands” or demonstrate other “normal” behaviors. Now, all of a sudden, a businessman writes about being able to concentrate better at staff meetings with a fidget toy. She concludes,

“Something that was considered entirely pathological and in dire need of correction when done by disabled people is now perfectly acceptable because it is being done by non-disabled people.”

Good point

Makes me think how some describe autism “behaviors” as meaningful and typical, but just occurring more frequently or intensely than those without autism might do.

One point worth considering

In defense of the teachers out there, I’m thinking of the “criteria” for a good fidget toy. I’ve listed them out in my speaking programs. For example:

Fidget spinners fall short for some of my criteria even though they rate very high on social interest.

Are there other options?

The problem with fads is that they go out as fast as they come in. I’ll bet that by the time the new school year starts in the fall, fidget spinners will be lying in the bottom of a drawer somewhere and there will be a new fad for a new school year.

What is your experience with fidget spinners or other fidget toys? I’d love to hear. Just click below or comment on my Facebook page.

https://www.facebook.com/lindahodgdon.autism

About The Author

Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP is a Speech-Language Pathologist who is internationally known as a pioneer in developing the use of visual strategies to support communication for students with the communication, behavior or social skill challenges that are common in Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD).

As an author, speaker and consultant, she has become well known world wide for her very practical information and strategies that guide communication partners to develop effective communication relationships with their children with autism.

With a focus on communication, Linda’s books and training programs are packed with “best-practices” and proven strategies for helping individuals from young children with autism through adults with Asperger’s participate more effectively in their life opportunities.