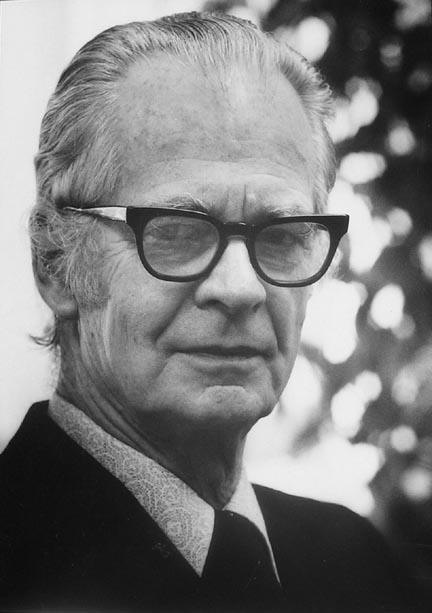

In B.F. Skinner’s phenomenal book The Technology of Teaching, he briefly discusses problems with punishment. He explains that the use of punishment (defined as adding or subtracting something from the environment in order to reduce the occurrence of a behavior), is not as clear-cut as we might imagine. When we attempt to punish a behavior, it’s quite likely that we will unintentionally suppress a broader range of behaviors than we intended.

In B.F. Skinner’s phenomenal book The Technology of Teaching, he briefly discusses problems with punishment. He explains that the use of punishment (defined as adding or subtracting something from the environment in order to reduce the occurrence of a behavior), is not as clear-cut as we might imagine. When we attempt to punish a behavior, it’s quite likely that we will unintentionally suppress a broader range of behaviors than we intended.

Skinner gives the example of a child who has touched a candle flame and been burned. The child has probably been taught not to touch the flame, but Skinner argues that it’s quite possible that “in the presence of a candle flame he will not be likely to explore any part of the environment, to reach for or grasp objects of any kind” (Skinner, 1968, p. 186). This is an important consideration, especially when we consider the classroom. We have to ask ourselves, when we punish certain behaviors, are we unintentionally suppressing other, desirable behaviors? And in punishing the undesirable behavior, are we clearly communicating to the child what the desirable behavior is?

Skinner then moves on to discuss alternatives to punishment. What he describes is known today as differential reinforcement. Since Skinner wrote The Technology of Teaching, a great deal of research has been completed on differential reinforcement, which “consists of reinforcing particular behavior(s) of a given class (or form, pattern or topography) while placing those same behaviors on extinction and/or punishing them when they fail to match performance standards or when they occur under inappropriate stimulus conditions” (Mayer, Sulzer-Azaroff, & Wallace, 2014). Put simply, we reinforce the desired behavior and do not reinforce the undesired behavior.

Today we have categories for many different types of differential reinforcement to better describe strategies for implementation.

Types of differential reinforcement include:

- Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior (DRA)

- Differential Reinforcement of Other Behavior (DRO)

- Differential Reinforcement of Incompatible Behavior (DRI)

- Differential Reinforcement of High Rates of Behavior (DRH)

- Differential Reinforcement of Low Rates of Behavior (DRL)

Differential reinforcement is an incredibly useful tool for teachers and parents. So we will devote several Tips of the Week over the upcoming months to how to use it effectively, taking a closer look at each of the types listed above.

References

Mayer, G. Roy, Sulzer-Azaroff-B. & Wallace, M. (2013). Behavior analysis for lasting change (3rd ed.). Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY: Sloan Publishing.

Skinner, B. F. (1968). The technology of teaching. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

WRITTEN BY SAM BLANCO, MSED, BCBA

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-12 in NYC. Working in education for ten years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam has developed strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently pursuing her PhD in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College.

Often, we focus on how to improve the behavior of an individual, but there are many times in which teachers must figure out a way to improve the behavior of the entire class. In ABA, we might implement a group contingency, a strategy in which reinforcement for the whole group is based upon the behavior of one or more people within the group meeting a performance criterion (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007).

Often, we focus on how to improve the behavior of an individual, but there are many times in which teachers must figure out a way to improve the behavior of the entire class. In ABA, we might implement a group contingency, a strategy in which reinforcement for the whole group is based upon the behavior of one or more people within the group meeting a performance criterion (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007).

Strengthen listening and speaking skills in your learner with this workbook by speech-language pathologist Jean Gilliam DeGaetano that contains 80 pages of reproducible Student and Instructor Worksheets. The worksheets cover 3 basic techniques – Yes or No Answers, Choosing Between Two Answers, and Completing Sentences. This week only, you can save 15%* on

Strengthen listening and speaking skills in your learner with this workbook by speech-language pathologist Jean Gilliam DeGaetano that contains 80 pages of reproducible Student and Instructor Worksheets. The worksheets cover 3 basic techniques – Yes or No Answers, Choosing Between Two Answers, and Completing Sentences. This week only, you can save 15%* on

In the study, there were three pairs of siblings. The ages of the children with autism ranged from 5 years old to 8 years old. The ages of the siblings ranged from 8 years old to 13 years old. The researchers trained each sibling of a child with autism how to teach basic skills, such as discriminating between different coins, identifying common objects, and spelling short words. As part of this training, the researchers showed videos of one-on-one sessions in which these skills were taught, utilizing techniques such as reinforcement, shaping, and chaining. What the researchers did next was the part that really stood out to me: they discussed with the siblings how to use these techniques in other environments. Finally, the researchers observed the sibling working with their brother/sister with autism and provided coaching on the techniques.

In the study, there were three pairs of siblings. The ages of the children with autism ranged from 5 years old to 8 years old. The ages of the siblings ranged from 8 years old to 13 years old. The researchers trained each sibling of a child with autism how to teach basic skills, such as discriminating between different coins, identifying common objects, and spelling short words. As part of this training, the researchers showed videos of one-on-one sessions in which these skills were taught, utilizing techniques such as reinforcement, shaping, and chaining. What the researchers did next was the part that really stood out to me: they discussed with the siblings how to use these techniques in other environments. Finally, the researchers observed the sibling working with their brother/sister with autism and provided coaching on the techniques.