Differential Reinforcement of High Rates of Behavior (DRH) is “reinforcing only after several responses occur at or above a pre-established rate” (Mayer, Sulzer-Azaroff, & Wallace, 2013). There are times when a behavior is already in a student’s repertoire, but you may want to increase the rate of the behavior.

For example, let’s say Harold frequently won’t get up independently on weekdays before school. It’s driving his parents crazy, because they have to drag him out of bed several days a week. You may set up a DRH to increase the rate of him getting up independently. Since Harold currently gets up independently at least one time per week, you would set the goal for two times per week. (You don’t want to set the goal too high, because then Harold might not ever come into contact with reinforcement, and his behavior will likely remain unchanged.) Let Harold know that if he gets up independently two days in a row, you will make his favorite breakfast on the second day. Once Harold has met this goal a few time, increase the requirement for reinforcement. You would move from two days in a row to three days in a row in order to receive his favorite breakfast.

For example, let’s say Harold frequently won’t get up independently on weekdays before school. It’s driving his parents crazy, because they have to drag him out of bed several days a week. You may set up a DRH to increase the rate of him getting up independently. Since Harold currently gets up independently at least one time per week, you would set the goal for two times per week. (You don’t want to set the goal too high, because then Harold might not ever come into contact with reinforcement, and his behavior will likely remain unchanged.) Let Harold know that if he gets up independently two days in a row, you will make his favorite breakfast on the second day. Once Harold has met this goal a few time, increase the requirement for reinforcement. You would move from two days in a row to three days in a row in order to receive his favorite breakfast.

You would continue this until you had reached a pre-arranged goal. It’s important to be realistic in our expectations. You don’t want to change the goal to quickly or make it unreachable. You also don’t want to place higher demands on an individual with disabilities than you do the general population (as discussed in our previous Simplifying the Science article). Many people, for instance, hit the snooze button several times before they actually get up, so it may not be necessary to require an individual with disabilities to wake up the very first time the alarm clock rings 100% of the time.

You may discover that your intervention with Harold is working quite well for a couple weeks, then suddenly stops working. You may need to backtrack a bit, and require fewer consecutive days of independently waking up. Or, you may need to vary the reinforcement. It’s possible that having his favorite breakfast has lost some of its power as a reinforcer.

Finally, after the behavior has reached your goal rate, you should begin to fade the reinforcement entirely. Of course, Harold should still have access to his favorite breakfast, but you should not continue to give it to him on the fifth consecutive day of waking up independently for years to come!

DRH is yet another variation of differential reinforcement that can be very useful for you. It’s also provides an opportunity for a much more positive interaction than introducing punishment to Harold for not waking up independently, and can decrease everyone’s stress levels at the beginning of the day.

References

Mayer, G. Roy, Sulzer-Azaroff-B. & Wallace, M. (2013). Behavior Analysis for Lasting Change-3rd ed. Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY: Sloan Publishing.

WRITTEN BY SAM BLANCO, MSED, BCBA

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-12 in NYC. Working in education for ten years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam has developed strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently pursuing her PhD in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College.

DRA is “a procedure for decreasing problem behavior in which reinforcement is delivered for a behavior that serves as a desirable alternative to the behavior targeted for reduction and withheld following instances of the problem behavior (e.g., reinforcing completion of academic worksheet items when the behavior targeted for reduction is talk-outs)” (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). The key thing to remember here is if you are implementing a DRA, a specified alternative behavior has been selected for reinforcement.

DRA is “a procedure for decreasing problem behavior in which reinforcement is delivered for a behavior that serves as a desirable alternative to the behavior targeted for reduction and withheld following instances of the problem behavior (e.g., reinforcing completion of academic worksheet items when the behavior targeted for reduction is talk-outs)” (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). The key thing to remember here is if you are implementing a DRA, a specified alternative behavior has been selected for reinforcement. DRI is not always the best option. For example, it may be very challenging to come up with an incompatible behavior. Or, in the case of self-injurious or aggressive behavior, it may be dangerous to use such an intervention.

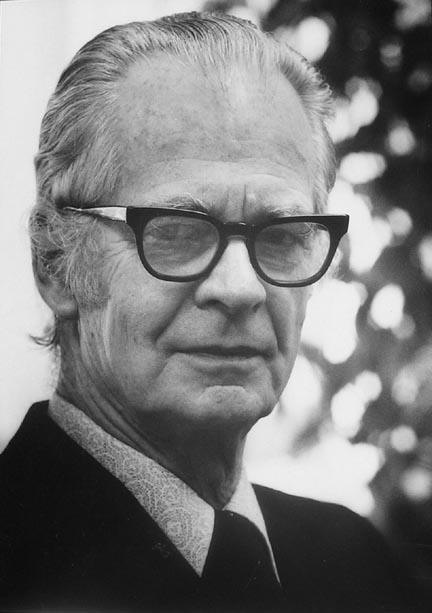

DRI is not always the best option. For example, it may be very challenging to come up with an incompatible behavior. Or, in the case of self-injurious or aggressive behavior, it may be dangerous to use such an intervention. In B.F. Skinner’s phenomenal book The Technology of Teaching, he briefly discusses problems with punishment. He explains that the use of punishment (defined as adding or subtracting something from the environment in order to reduce the occurrence of a behavior), is not as clear-cut as we might imagine. When we attempt to punish a behavior, it’s quite likely that we will unintentionally suppress a broader range of behaviors than we intended.

In B.F. Skinner’s phenomenal book The Technology of Teaching, he briefly discusses problems with punishment. He explains that the use of punishment (defined as adding or subtracting something from the environment in order to reduce the occurrence of a behavior), is not as clear-cut as we might imagine. When we attempt to punish a behavior, it’s quite likely that we will unintentionally suppress a broader range of behaviors than we intended.