By: Nicole Gorden, M.S., BCBA, LBA

Autism spectrum disorder occurs in individuals from many different cultures and backgrounds. Therefore, cultural competency and sensitivity is imperative for effective delivery of services. To work with autistic learners, is to respect that they are the product of many environments that have shaped them and will continue to shape them throughout their life.

As stated in the most updated ethical code from the BACB, behavior analysts are responsible for incorporating and addressing diversity in practice. For example, the BACB ethical code states that behavior analysts must practice within our scope of competence, maintain competence including cultural responsiveness and diversity. Specifically, providers must “evaluate their own biases and ability to address the needs of individuals with diverse needs/backgrounds” (Ethical Code, 2022, 1.07).

However, what are the practical implementations to culturally sensitive treatment? What does this actually look like in practice? As providers, we are obligated to offer exceptional service delivery with individualized treatment goals. Considering our learner’s cultural background and the impact of their community’s beliefs and attitudes is essential to effective treatment. The following will provide guidance on how providers can apply cultural sensitivity to their clinical decisions in treatment.

Awareness of Own Cultural Biases

Cultural awareness is the first step to providing culturally ethical treatment. Providers should concurrently and habitually engage in practices in which they remain aware of their own predetermined perceptions and acknowledge their own limitations to cultural competency. As mentioned in Fong et. al (2016), “cultural awareness may be important because behavioral patterns that are viewed as problematic in our own culture may be the norm in other cultures”. Due to limitations in diversity within most helping professions, a learner’s provider is often from a different cultural background.

Thus, it is essential to understand the traditions of that culture. As an example, physical punishment may be common practice in some black communities which has been perceived to be deeply rooted in racial trauma (Patton, 2017). It would be insensitive for a provider from a different cultural background to ignore that this practice is a cultural tradition, and thus blame or stigmatize black parents for their choices. Rather, “professionals can offer information about why the practice is harmful but have been told it is necessary, and offer healthier alternatives that produce better outcomes for children, families and communities” (Patton, 2017). Cultural sensitivity is facilitating the development of our programs by checking our own biases and how they may affect our choices in treatment.

Selection of Target Behaviors and Programmatic Materials

A few years ago, a client from Asian descent was transferred to me from another behavior analyst. When assessing the barriers to treatment, my client made minimal progress when asked to identify a fork. Believing that an object, rather than a picture might help, I asked the client’s parents for a fork. When obtaining the fork, the parents expressed that they do not use forks to eat. In their culture, hands and chopsticks are typical eating utensils. Thus, when considering cultural sensitivity, this includes selecting programmatic targets that are common in the client’s environment and the cultural norms.

The teaching materials should be as individualized as the treatment plan too. We should rely on diverse representation in the resources we use in treatment. Providers should use materials that represent the individual’s environment, which is typically a blend of many different ethnicities. When providing resources like visual schedules, do your cartoons or pictures represent the racial identity of your learner? If you are teaching body parts on a doll, do you provide toys that look like your learner? To be a culturally sensitive professional, one should give precedence to ethnic representation to allow the learner to feel validated and treat them with dignity.

The cultural assessment process should be used to inform treatment, specifically when designing the program for validity and selecting targets for skill acquisition (Fong et. al, 2016). When beginning a new lesson or treatment program, it is essential that providers select socially meaningful and significant target goals. However, in selecting these goals for treatment, professionals must consider the cultural norms and needs of the client.

About the Author:

Nicole Gorden, M.S., BCBA, LBA has over 14 years of experience implementing Applied Behavior Analysis principles with the Autism Population. She currently works for Comprehensive Behavior Supports in Brooklyn, NY.

References:

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. Littleton, CO: Author.

DuBay, M., Watson, L. R., & Zhang, W. (2018). In Search of Culturally Appropriate Autism Interventions: Perspectives of Latino Caregivers. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 48(5), 1623–1639.

Fong, E. H., Catagnus, R. M., Brodhead, M. T., Quigley, S., & Field, S. (2016). Developing the Cultural Awareness Skills of Behavior Analysts. Behavior analysis in practice, 9(1), 84–94.

Fong, E. H., Ficklin, S., & Lee, H. Y. (2017). Increasing cultural understanding and diversity in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(2), 103-113.

Patton, S. (2017, April). Corporal punishment in black communities: Not an intrinsic cultural tradition but racial trauma. CYF News. http://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2017/04/racial-trauma

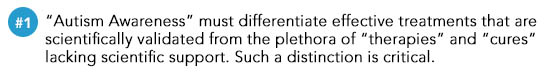

Learning that your child has autism is incredibly overwhelming. You’re under intense stress to make the best decisions possible for your child, and to do so quickly. Add to the fact that autism is a popular topic in the news and social media, so tips and quick fixes frequently show up in headlines and news feeds. Autism is considered to be a fad treatment magnet, and while some of the fad treatments are ineffective, others are flat out dangerous. How is it possible to parse through all this to find reliable information? Here are a few tips to help you out:

Learning that your child has autism is incredibly overwhelming. You’re under intense stress to make the best decisions possible for your child, and to do so quickly. Add to the fact that autism is a popular topic in the news and social media, so tips and quick fixes frequently show up in headlines and news feeds. Autism is considered to be a fad treatment magnet, and while some of the fad treatments are ineffective, others are flat out dangerous. How is it possible to parse through all this to find reliable information? Here are a few tips to help you out: So where can you find valid information?

So where can you find valid information?

Do you know of any upcoming conference or workshops on Autism?! Please let us know of any ABA, Verbal Behavior or Speech-Language Therapy events and we will share it with our community. We strive to help our readers be informed about resources and events for parents and educators of children with autism or other developmental delays. No matter how big or how small – email info about your event to

Do you know of any upcoming conference or workshops on Autism?! Please let us know of any ABA, Verbal Behavior or Speech-Language Therapy events and we will share it with our community. We strive to help our readers be informed about resources and events for parents and educators of children with autism or other developmental delays. No matter how big or how small – email info about your event to  Bridge Kids Social Circle

Bridge Kids Social Circle Bridge Kids Happy Eaters Group

Bridge Kids Happy Eaters Group