We’re so thrilled to be kicking off Autism Awareness Month with a special guest article from the Executive Director of the Association for Science in Autism Treatment (ASAT) David Celiberti, PhD, BCBA-D, who shares with us 10 things autism awareness should be about. David has also provided a wealth of information and resources for parents and professionals to utilize in finding the best treatments out there, seeking out reliable research and asking good questions, helping individuals with ASD find a place in the workforce, and much more. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook!

10 Things Autism Awareness SHOULD Be About

by David Celiberti, PhD, BCBA-D

April is Autism Awareness Month. The blue puzzle pieces will appear on thousands of Facebook pages and billboards, and the media will give greater attention to, and information about autism. Further awareness is a wonderful thing, as detection and diagnosis are necessary first steps to accessing help in the form of treatment, information, and support. With well over 400 treatments from which to choose, parents of children with autism need guidance, tools, and accurate information to make the best possible choices for their children: choices that will undoubtedly have a profound impact on both their current quality of life and their children’s future.

Clearly, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is no longer the rare diagnosis that it once was. With the incidence of one in 68 children, and one in 42 boys, our own families, neighbors, and co-workers are all touched by autism. In fact, the sheer numbers have heightened awareness of autism in and of themselves. This awareness is essential: it promotes early detection, and with early detection, we hope for a relatively clearer course toward effective treatment and better outcomes. Sadly, however, the early detection of autism alone does not always mean a seamless path to intervention. Furthermore, families whose children are diagnosed with autism are still not able to expeditiously access the most effective science-based treatments available. Instead, families often have to sort through over 400 pseudo-scientific treatments until they arrive at the most effective and research-proven intervention in addressing the complex disorder of autism. We must do better!

“Autism Awareness” should be about more than just detection and diagnosis. It has always been ASAT’s hope that the conversation around autism awareness would be broadened to focus upon the obstacles that separate individuals with autism from effective, science-based intervention and distract their families, caregivers, and teachers from accurate information about effective autism intervention. Below are 10 ideas about what Autism Awareness should be about, along with ways that the Association for Science in Autism Treatment (ASAT) can assist families and providers in navigating the complex maze of autism treatment options.

Autism treatment is a multi-million dollar industry. For the majority of the 400+ available interventions, science is overlooked in favor of pseudoscience, and they are marketed with heart-wrenching testimonials, anecdotes and video montages, and often bolstered with poorly crafted and misleading surveys. Many boast inaccurate and even outrageous claims that are touted as evidence of effectiveness. Aggressive marketing of these so-called “therapies” and “cures” is absolutely overwhelming and it drowns out accurate information for parents who are desperate to help their children.

For most other medical conditions, a provider who disregards a proven intervention in favor of using a “fringe” treatment could be sued for malpractice! Such safeguards do not widely exist for autism treatment. We do no favors for children with autism, their families, and those charged with providing effective services when we not only ignore quackery, but allow it to proliferate by failing to counter baseless claims. Families deserve better. Individuals with autism deserve better. Visit our website to learn more about the scientific support behind various autism treatments, the relevance of peer-reviewed research, the pitfalls of testimonials, as well as many other articles related to becoming a more savvy consumer. Please also see our review of Sabrina Freeman’s book, A Complete Guide to Autism Treatments.

As adults, voters, consumers, providers, and parents, choice underlies all of our decisions. Decision-making power comes with tremendous responsibility. There is a myriad of stakeholders whose decisions have profound implications for children and adults with autism – not just parents, but siblings, teachers, treatment providers, administrators, program coordinators, and taxpayers.

- Scientists need to take responsibility in making their findings about an intervention’s effectiveness clear, unambiguous, and unexaggerated. Efforts should be taken to promote replication.

- Administrators and program leaders need to take responsibility in identifying internal and external training opportunities that further their staff’s competence with evidence-based practice. Additionally, they should make sure their staff receives the support needed to sustain these efforts and to continually engage in data-based decision making when both selecting and monitoring interventions. They must be savvy and selective in their selections of trainings for their staff and not fall prey to gimmicks, splashy sales pitches or fads.

- Providers need to select procedures that are based on published research, adhere to their discipline’s ethical guidelines about evidence-based practices, and maintain a commitment to ensuring that parents have truly been given the opportunity to provide informed consent. For example, if there is no scientific evidence to support an intervention that one is using, then it is an ethical obligation of the professional to inform parents of this lack of evidence. Please see Principle #1 and #2 of the Ethical Code for Occupational Therapists, Section 2.04 of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, and Section 2 of the Guidelines for Responsible Conduct for Behavior Analysts.

- Parents must continue to exercise caution in sorting through autism treatment options to make the best possible choice for their children, particularly since many providers do not make the path to effective treatment clear and simple.

There are far too many individuals with autism who do not have access to effective treatment, are receiving ineffective treatment, or are subjected to treatments that are, in fact, dangerous. Every minute of ineffective intervention is one less minute spent accessing effective intervention. Every dollar spent on an intervention that does not work depletes resources available for interventions that do work. For questions to ask to make sure that the individual with autism in your life is receiving science-based treatment, please see our article on questions to ask marketers and read more about the following three phases of inquiry about particular interventions and their associated questions and considerations in The Road Less Traveled: Charting a Clear Course for Autism Treatment:

- Phase I: Exploring the viability and appropriateness of a particular treatment approach.

- Phase II: Assessing the appropriateness of an intervention under the supervision of a specific service provider for a specific individual with autism.

- Phase III: Monitoring the implementation of the treatment and evaluating effectiveness.

As we know, not all information on the Internet is reliable and accurate. You have probably heard the term, caveat emptor (“Let the buyer beware”). Consumers must also practice caveat lector (“Let the reader beware”).

Often Internet information is deemed equivalent in relevance, importance, and validity to research published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, but it is not. Testimonials and uncontrolled studies from so-called researchers can lead parents astray and be a tremendous source of distraction. Parents of newly-diagnosed children may be particularly vulnerable. Know the red flags to avoid and learn how to evaluate research by visiting our website. Our library of articles highlights scientific concepts and methods as they relate to potential autism interventions, with the goal of providing families, educators and clinicians with the information they need in order to be savvy consumers of marketed treatment products and therapies.

Continue reading →

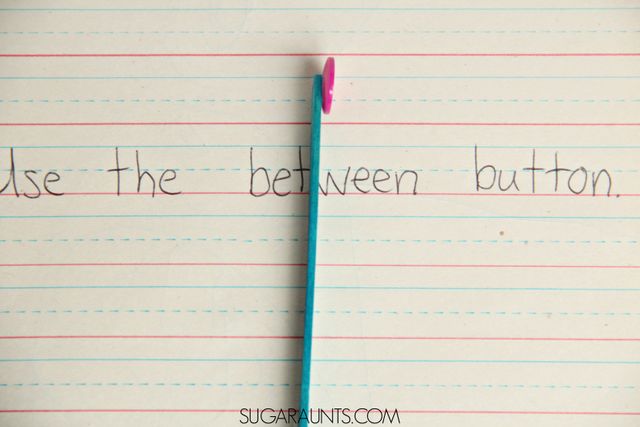

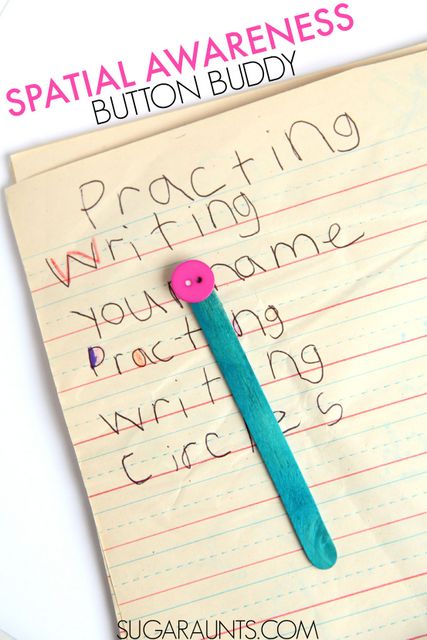

Looking for a simple tool to help improve your student’s handwriting skills? Check out this super easy, DIY solution from

Looking for a simple tool to help improve your student’s handwriting skills? Check out this super easy, DIY solution from