This month’s featured article from ASAT is by Program Director of the Kansas City Autism Training Center Tanya Baynham, MS, BCBA, on a variety of research-based strategies to help you expand interests in children with autism. To learn more about ASAT, please visit their website at www.asatonline.org. You can also sign up for ASAT’s free newsletter, Science in Autism Treatment, and like them on Facebook!

My child is doing well with many of his ABA programs, even the ones that focus on the development of play skills. Unfortunately, he doesn’t play with most of the toys that we give him, and he has worked for the same five things since our program began a year ago (marshmallow peeps, Thomas trains, tickles, Wiggles songs, and raisins). What can I do to expand his interests and maybe even get those interests to function as reinforcers for teaching targets?

Answered by Tanya Baynham, MS, BCBA

Program Director, Kansas City Autism Training Center

Inherent to a diagnosis of autism is the observation that the child will engage in restricted or repetitive behavior and may also display restricted interests. Expanding those interests, specifically in the areas of toy use and play, is an important programming goal as it can result in a number of positive effects. First, rates of socially appropriate behaviors may increase while rates of inappropriate behaviors may decrease. For example, engaging a child in looking at a book may decrease stereotypic behaviors or passivity (Nuzzolo-Gomez, Leonard, Ortiz, Rivera, & Greer, 2002). Second, interest expansion can lead to new social opportunities for children and promote greater flexibility when bringing them to new environments. For example, a child with a new preference for coloring may be more successful in a restaurant because he will sit and color the menu, or he can attend Sunday school because he will color a picture when directed. Third, the addition of new reinforcers in ABA programs may help prevent satiation or allow you to allocate more highly preferred items for difficult teaching targets and less preferred items for easier targets.

Stocco, Thompson, and Rodriguez (2011) showed that teachers are likely to present fewer options to individuals with restricted interests and will allow them to engage longer with items associated with those restricted interests. The authors suggest one possible reason for this is that teachers might be sensitive to the fact that negative behaviors (e.g., whining, pushing the toy away) are more likely to accompany the presentation of a toy that is not associated with the child’s restricted interest. In general, this sensitivity to the child’s behavior is important in maintaining low rates of problem behavior, but it can potentially limit access to novel experiences or activities. We need to systematically program effective ways to expand a child’s interests without evoking tears and other negative behavior.

Most importantly we, as parents and intervention providers, must make reinforcer expansion a teaching focus and use data to determine whether our procedures are producing change. One recommendation is to first track the number of different toys and activities with which your child engages to identify current patterns. Then, measure the effects of attempts at reinforcer expansion on your child’s behavior. Ala’i-Rosales, Zeug, and Baynham (2008) suggested a variety of measures that can be helpful in determining whether your child’s world is expanding. These measures include the number of toys presented, number of different toys approached/contacted across a week (in and/or out of session), engagement duration with new toys, and affect while engaging with toys. It is sometimes helpful to track changes across specific categories (e.g., social activities, food, social toys, sensory toys, etc.). If, for example, your child only watches Thomas videos, you may narrow the focus to the category “videos” in order to track expansion of interests to different types of videos. Keeping in mind the previous point about a teacher’s role in expanding a child’s interests, you may also want to set goals to ensure changes in adult behavior such as, “Present three new items each day.”

Once data are being taken, it is important to implement procedures likely to expand your child’s interests. One way to expand toy play is to present, or pair, a preferred item with the item you want to become more preferred (Ardoin, Martens, Wolfe, Hilt and Rosenthal, 2004). Here are a few examples:

- Playing a game: Use peeps as the game pieces in a game you want your child to enjoy, embedding opportunities to eat the peeps at different points during the game.

- Trying a new activity: Sing a favorite song as you help your child up the ladder of an unfamiliar slide on the playground.

- Reading a book: Tickle your child before turning each page while reading a book.

A second way to expand interests is to think about why your child might engage in those restricted interests. If he likes Thomas because of the happy face, put Thomas stickers on a ring stacker. If he likes Thomas because of the wheels, present other vehicles with wheels. If your child likes peeps because they blow up in the microwave, put Mentos in a cola bottle or use baking soda to make a volcano. If he likes peeps because they are squishy, use marshmallows in art projects or in a match-by-feel game.

A third way to expand interests is described by Singer-Dudek, Oblak, and Greer (2011), who demonstrated that some children will engage more with a novel toy after simply observing another child receiving reinforcers after playing with it. To apply these findings to your child, give Thomas trains, if they are used as a reinforcer, to a sibling who just played with novel items such as play dough or shaving cream. Continue reading →

Teaching Kids of All Ages to Ask Questions is a great source for teaching students at different levels how to ask and answer questions. The book also covers:

Teaching Kids of All Ages to Ask Questions is a great source for teaching students at different levels how to ask and answer questions. The book also covers: Teaching Conversation to Children with Autism Scripts and Script Fading provides step-by-step instructions to parents and teachers on how to teach conversation skills. Because many individuals with autism have difficulty initiating and maintaining conversation, this book describes how scripts and script fading can provide a predictable and meaningful structure for these individuals to engage in conversation. The goal is for these scripts to then progress to spontaneous language. This book covers: scripts for readers and non-readers; conversation activities; activity schedules; prompts and rewards; and observing, evaluating and measuring results.

Teaching Conversation to Children with Autism Scripts and Script Fading provides step-by-step instructions to parents and teachers on how to teach conversation skills. Because many individuals with autism have difficulty initiating and maintaining conversation, this book describes how scripts and script fading can provide a predictable and meaningful structure for these individuals to engage in conversation. The goal is for these scripts to then progress to spontaneous language. This book covers: scripts for readers and non-readers; conversation activities; activity schedules; prompts and rewards; and observing, evaluating and measuring results. Teach Me Language is a social language manual for children with autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and related developmental disorders. Based on professional speech pathology methods, this book targets social language, general knowledge, grammar and syntax, functional knowledge, written expression and language-based academic concepts. Teach Me Language is designed to take the child from one and two word utterances to more complex sentences that lay the foundation for social conversation.

Teach Me Language is a social language manual for children with autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and related developmental disorders. Based on professional speech pathology methods, this book targets social language, general knowledge, grammar and syntax, functional knowledge, written expression and language-based academic concepts. Teach Me Language is designed to take the child from one and two word utterances to more complex sentences that lay the foundation for social conversation.

For many individuals with autism, routine appointments such as medical, dental and haircuts can be extremely difficult to tolerate. There are many factors that may contribute to this intolerance such as novel environments, novel adults, novel or aversive sounds, bright lights, foreign tastes, painful sensations, sitting for long periods of time and physical touch. As a result, many children with autism display noncompliant or avoidant behavior in response to these stimuli or events. Fortunately, there is a growing body of research published in peer-reviewed journals describing effective strategies to target dental toleration. Several different behavior interventions and programs have been used to increase an individual’s tolerance or proximity to an avoided stimulus or event, such as a dental exam. For example, the use of escape and reward contingent on cooperative dental behavior was shown to be effective for some individuals (Allen & Stokes, 1987; Allen, Loiben, Aleen, & Stanley, 1992). Non-contingent escape, in which the child was given periodic breaks during the dental exam, was also effective in decreasing disruptive behavior (O’Callaghan, Allen, Powell, & Salama, 2006). Other strategies such as using distraction and rewards (Stark et al., 1989), providing opportunities for the individuals to participate in the dental exam (Conyers et al., 2004), and employing systematic desensitization procedures (Altabet, 2002) have been shown to be effective. Most recently, Cuvo, Godard, Huckfeldt, and Demattei (2010) used a combination of interventions including, priming DVD, escape extinction, stimulus fading, distracting stimuli, etc. The board certified behavior analyst overseeing your daughter’s program is likely familiar with these procedures.

For many individuals with autism, routine appointments such as medical, dental and haircuts can be extremely difficult to tolerate. There are many factors that may contribute to this intolerance such as novel environments, novel adults, novel or aversive sounds, bright lights, foreign tastes, painful sensations, sitting for long periods of time and physical touch. As a result, many children with autism display noncompliant or avoidant behavior in response to these stimuli or events. Fortunately, there is a growing body of research published in peer-reviewed journals describing effective strategies to target dental toleration. Several different behavior interventions and programs have been used to increase an individual’s tolerance or proximity to an avoided stimulus or event, such as a dental exam. For example, the use of escape and reward contingent on cooperative dental behavior was shown to be effective for some individuals (Allen & Stokes, 1987; Allen, Loiben, Aleen, & Stanley, 1992). Non-contingent escape, in which the child was given periodic breaks during the dental exam, was also effective in decreasing disruptive behavior (O’Callaghan, Allen, Powell, & Salama, 2006). Other strategies such as using distraction and rewards (Stark et al., 1989), providing opportunities for the individuals to participate in the dental exam (Conyers et al., 2004), and employing systematic desensitization procedures (Altabet, 2002) have been shown to be effective. Most recently, Cuvo, Godard, Huckfeldt, and Demattei (2010) used a combination of interventions including, priming DVD, escape extinction, stimulus fading, distracting stimuli, etc. The board certified behavior analyst overseeing your daughter’s program is likely familiar with these procedures.

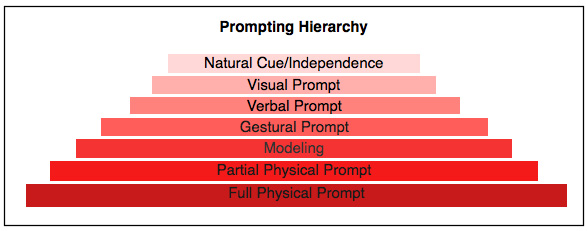

If I were to ask you right now, what types of activities does your learner like to do, and what types of activities is your learner resistant to, you’d probably be able to respond pretty quickly to both questions. For instance, you might say, my son loves to practice addition facts, but he is resistant to working on spelling homework. Or you might say, my student enjoys passing out papers in class, but is resistant to lining up with the rest of the class when it’s time to go to lunch.

If I were to ask you right now, what types of activities does your learner like to do, and what types of activities is your learner resistant to, you’d probably be able to respond pretty quickly to both questions. For instance, you might say, my son loves to practice addition facts, but he is resistant to working on spelling homework. Or you might say, my student enjoys passing out papers in class, but is resistant to lining up with the rest of the class when it’s time to go to lunch.

overing 6 different topics –

overing 6 different topics –