Every parent wants their child to succeed in school. The definition of success may differ from parent to parent, but most would agree that they want their child to get good grades, demonstrate good behavior and make friends. These desires are no different for parents who have children with developmental disabilities. So, how do you know if your child is ready and are there ways to predict how well they will do? Tools like the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP), which is one of the primary assessment tools used at the Behavior Analysis Center for Autism (BACA), can assist parents and professionals alike in assessing their child’s skills and providing them with valuable information as to what areas they can support their child to increase the chances of them doing well in whatever educational setting they may enter.

General skill deficits will likely determine the educational placement of your child, but may not be the biggest issue at hand.

Behavior problems and problems with instructional control can cause significant barriers to achievement with grades, developing friendships and avoiding expulsion. Learned prompt dependency may make developing independence and responsibility more difficult. Failure to generalize already existing knowledge across multiple examples, people and environments will require more teaching time and may manifest inconsistent performance on tests and classroom work. If your child likes very few things, seemingly peculiar things, or has strong motivation for some things, but is unwilling to work to attain them, it may make it more difficult to motivate them to learn material that is presented. If your child is reliant on getting something for responding every time in order for learning to occur, the teaching process will likely remain a tedious one and decrease the likelihood that they will be able to maintain those responses when those incentives are not provided as frequently. Many children with developmental disabilities will rely on providing themselves with reinforcement in the form of self-stimulation when such dense access to preferred items or activities is not provided.

Overall skill level will undoubtedly increase the odds that your child will be able to manage good grades. However, their ability to acquire new material quickly and then retain that information for later use may play a more critical role in their long term accomplishment. Adapting to change quickly or ‘going with the flow’ will be critical when faced with day to day schedule changes that occur in classrooms or other instructional environments. General independence with functional skills such as toileting, eating and managing their personal items such as backpacks, folders, etc., will decrease the amount of time their teachers may need to focus on teaching these skills and allow more time for teaching other critical skills.

All of these things taken together can seem daunting, even for parents of typically developing children. The good news is that there are things that every parent can do to help. Perfect parenting is unattainable, but valiant and consistent attempts with certain things can go a long way. Allowing your child to experience the consequences of their behavior can be tough, but is central to ensuring that they will behave well when it counts. Having your child try things on their own before helping them and then only helping them as much as needed to get the job done whenever possible will foster independence. Exposing your child to new or different things within fun activities can increase the things they are interested in. Those things can then be used to motivate them to learn. Setting up opportunities for them to experience even small changes, modeling a calm demeanor and praising them for doing the same when unexpected things happen can also help.

Your child’s teacher or other professionals like Board Certified Behavior Analysts can aid you in thinking of other ways to enhance what you are already doing and assist in developing an individualized treatment plan to support you and your child.

WRITTEN BY MELANY SHAMPO, MA, BCBA

Melany Shampo is a clinical director at the Behavior Analysis Center for Autism in Fishers, IN.

This post first appeared on Indy’s Special Child.

Social Information Processing (SIP) is a widely studied framework for understanding why some children and adolescents have difficulty getting along with their peers and adults.

Social Information Processing (SIP) is a widely studied framework for understanding why some children and adolescents have difficulty getting along with their peers and adults. The

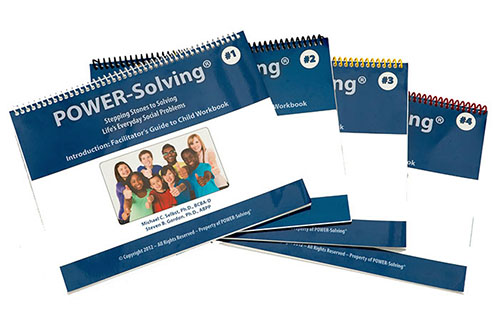

The  Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP is the Founder and Executive Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a clinical psychologist and is licensed in New Jersey. Dr. Gordon is also Board Certified in Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology by the American Board of Professional Psychology and is a Diplomate in Behavior Therapy from the American Board of Behavioral Psychology. Dr. Gordon has co-authored three books, published numerous articles, presented papers at local and national conferences, and served on editorial boards of professional journals. Most recently, Dr. Gordon and Dr. Selbst have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program

Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP is the Founder and Executive Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a clinical psychologist and is licensed in New Jersey. Dr. Gordon is also Board Certified in Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology by the American Board of Professional Psychology and is a Diplomate in Behavior Therapy from the American Board of Behavioral Psychology. Dr. Gordon has co-authored three books, published numerous articles, presented papers at local and national conferences, and served on editorial boards of professional journals. Most recently, Dr. Gordon and Dr. Selbst have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program  Michael C. Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D is Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a Licensed Psychologist and a Certified School Psychologist in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. He is also a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral level. Dr. Selbst has co-founded and is the Executive Director of HI-STEP® Summer Program, which is an intensive five-week day program for children to improve their social skills and problem solving ability, and the Director of the Weekend to Improve Social Effectiveness (W.I.S.E.). He has extensive experience working with pre-school aged children through adults, including individuals who have social skills deficits, emotional and behavioral difficulties, learning disabilities, gifted, and children with developmental delays, including those with Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome. Dr. Selbst consults to numerous public and private schools, assisting parents, teachers, and mental health professionals, and presents workshops on all topics highlighted above, as well as Parenting Strategies, Depression, and Suicide Prevention. Dr. Selbst and Dr. Gordon have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program

Michael C. Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D is Director of Behavior Therapy Associates, P.A. He is a Licensed Psychologist and a Certified School Psychologist in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. He is also a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral level. Dr. Selbst has co-founded and is the Executive Director of HI-STEP® Summer Program, which is an intensive five-week day program for children to improve their social skills and problem solving ability, and the Director of the Weekend to Improve Social Effectiveness (W.I.S.E.). He has extensive experience working with pre-school aged children through adults, including individuals who have social skills deficits, emotional and behavioral difficulties, learning disabilities, gifted, and children with developmental delays, including those with Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome. Dr. Selbst consults to numerous public and private schools, assisting parents, teachers, and mental health professionals, and presents workshops on all topics highlighted above, as well as Parenting Strategies, Depression, and Suicide Prevention. Dr. Selbst and Dr. Gordon have co-authored the new social-emotional skills program  While I find a specific tool like the

While I find a specific tool like the

Don’t let picky eating ruin meal time or divide your family at the dinner table. Encouraging healthy eating habits with a stubborn child requires patience with a firm touch. Here at Kutest Kids Early Intervention Center, our therapists are all too familiar with this phenomenon and would like share some common tips. Begin by setting the stage for healthy choices, thereby helping your child overcome their picky habits with a few key strategies.

Don’t let picky eating ruin meal time or divide your family at the dinner table. Encouraging healthy eating habits with a stubborn child requires patience with a firm touch. Here at Kutest Kids Early Intervention Center, our therapists are all too familiar with this phenomenon and would like share some common tips. Begin by setting the stage for healthy choices, thereby helping your child overcome their picky habits with a few key strategies.

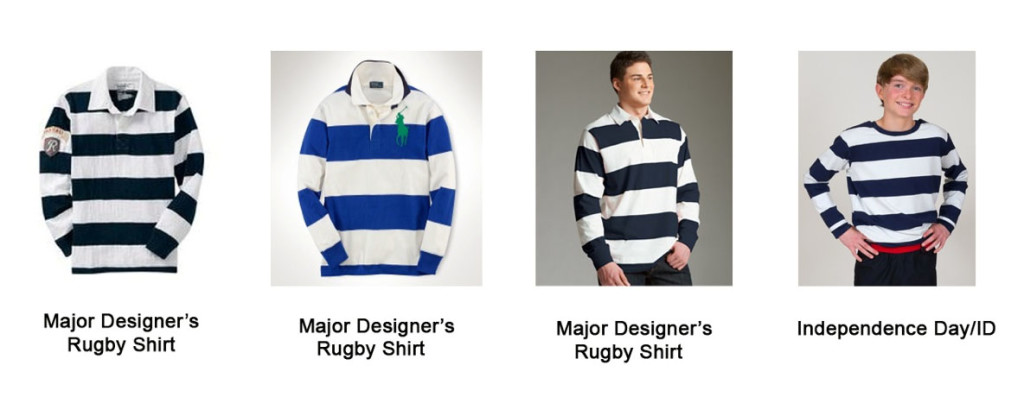

Because I’m an autism mom. That makes me a warrior mom. An activist mom. Someone who sees a lot of families, like mine, just trying to get through the day with a kid who can’t dress himself, except in baggy sweats and mono-color T-shirts. Even then, my Liam runs a 50% chance of getting those clothes on backwards. Or inside out. Or some other way that embarrasses his siblings and starts our day off under a cloud.

Because I’m an autism mom. That makes me a warrior mom. An activist mom. Someone who sees a lot of families, like mine, just trying to get through the day with a kid who can’t dress himself, except in baggy sweats and mono-color T-shirts. Even then, my Liam runs a 50% chance of getting those clothes on backwards. Or inside out. Or some other way that embarrasses his siblings and starts our day off under a cloud. I quit my job as a CNN Financial news anchor to take care of my son and advocate for autism causes. I shot a documentary, “Autism Every Day,” which premiered at Sundance. Shooting that doc, I spent 24 hours in the homes of 8 “autism families.” I saw that, like my son, these kids learned by “rote” the fundamentals of dressing. But due to simple design obstacles like “fronts and backs,” there was a wide margin for error. That was my first “focus group” on the dressing issue, all down on film.

I quit my job as a CNN Financial news anchor to take care of my son and advocate for autism causes. I shot a documentary, “Autism Every Day,” which premiered at Sundance. Shooting that doc, I spent 24 hours in the homes of 8 “autism families.” I saw that, like my son, these kids learned by “rote” the fundamentals of dressing. But due to simple design obstacles like “fronts and backs,” there was a wide margin for error. That was my first “focus group” on the dressing issue, all down on film. Lauren Thierry is the founder of

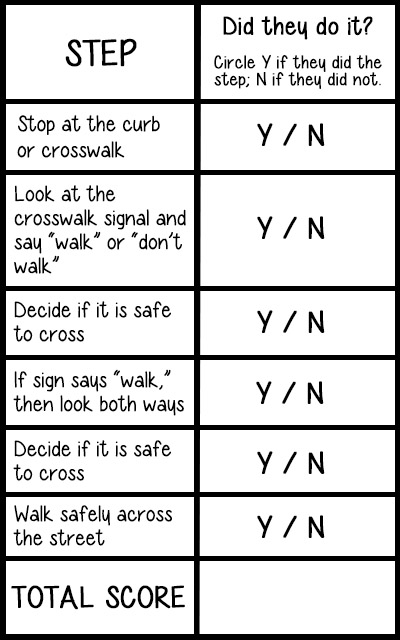

Lauren Thierry is the founder of  I am passionate about empowering children with special needs and their families with skills and knowledge that they can use to improve their quality of life. This is why I am super excited to be sharing tips and strategies that relate to keeping your child with autism safe on the street. Learning to navigate the real world involves a lot of complex skills that we sometimes take for granted. For example, learning to determine when it is safe to cross the street requires the ability to attend to your environment, the ability to identify moving cars from cars that are still, the ability to identify the signal at the cross walk that lets you know it is safe to cross, among many, many, more. In some cases even more advanced problem solving is required because if the sign says it is safe to cross and a motorist continues through the intersection we need to be able to identify the moving car is approaching and that we need to wait for it to pass before crossing the street. So where do we begin?

I am passionate about empowering children with special needs and their families with skills and knowledge that they can use to improve their quality of life. This is why I am super excited to be sharing tips and strategies that relate to keeping your child with autism safe on the street. Learning to navigate the real world involves a lot of complex skills that we sometimes take for granted. For example, learning to determine when it is safe to cross the street requires the ability to attend to your environment, the ability to identify moving cars from cars that are still, the ability to identify the signal at the cross walk that lets you know it is safe to cross, among many, many, more. In some cases even more advanced problem solving is required because if the sign says it is safe to cross and a motorist continues through the intersection we need to be able to identify the moving car is approaching and that we need to wait for it to pass before crossing the street. So where do we begin?