For parents, it can be difficult and frustrating to help their children through tantrums. We’re pleased to share with you a second guest post by Bridge Kids of New York (BKNY), who shares with us a few (humorous) words of advice on tackling tantrums.

T-A-N-T-R-U-M-S

by Bridge Kids of New York

Here at BKNY, parents reach out to us for support in a variety of areas. Not surprisingly, one of the most popular reasons we hear from parents is for support in managing tantrums! Why is this not surprising? Well, it’s not surprising because very few of us will make it through life without ever throwing a tantrum! We’ve all been there, right? Whether you were 5 or 35, you’ve most likely engaged in a tantrum. For our little ones, who are still learning about rules, expectations, effective behavior, and self-control, it makes sense that we will periodically see a tantrum—it’s often part of the learning process. So, for all of our parents out there who are tackling tantrums, here are a few words of advice for you:

Here at BKNY, parents reach out to us for support in a variety of areas. Not surprisingly, one of the most popular reasons we hear from parents is for support in managing tantrums! Why is this not surprising? Well, it’s not surprising because very few of us will make it through life without ever throwing a tantrum! We’ve all been there, right? Whether you were 5 or 35, you’ve most likely engaged in a tantrum. For our little ones, who are still learning about rules, expectations, effective behavior, and self-control, it makes sense that we will periodically see a tantrum—it’s often part of the learning process. So, for all of our parents out there who are tackling tantrums, here are a few words of advice for you:

Take a deep breath

Analyze why the tantrum is occurring and Avoid reinforcing it

Neutral tone and affect

Tune out the bystanders

Remember the big picture

Understand that this is a learning moment for your child

Make objective decisions rather than emotional ones

Stop beating yourself up

Take a deep breath.

Tantrums can be stressful for everyone involved! As a parent, it may be emotionally difficult, frustrating, or potentially embarrassing to work through a massive tantrum with your child–these are common emotions! But here’s the thing: when your child is mid-tantrum and about as far away from calm as possible, that’s when it’s the most important for us to be calm. After all, someone has to be! Whatever emotions you feel in these moments are perfectly valid—acknowledge them—then take a deep breath and try to release them. One of the most important things you can do for your child during a tantrum is to remain calm

Analyze why the tantrum is occurring and Avoid reinforcing it.

All behavior occurs for a reason. Whether or not you fully understand your child’s tantrum, rest assured that there is a function behind it. In order to handle it appropriately and use proactive measures in the future, we need to analyze what is going on. We need you to become a tantrum detective! Think about what happened right before your child’s tantrum (i.e. the antecedent). Were you talking on the phone instead of paying attention to her? Did he have to share a favorite toy with another child? Did you ask him to do something challenging? Looking at what happened right before will probably give you some information about why the tantrum is happening. Thinking about (and potentially reconsidering) how you typically respond in these situations may also help. Once you determine why the tantrum is occurring, the next step is to not give into it. So, if your child is tantrumming in the middle of the grocery store because you said “no” to the box of over-processed chocolate cereal, you want to make sure that you do not give in and buy the cereal.  If you cave during a tantrum, you will likely reinforce that behavior and see it again in the future. So do your best to stay strong!

If you cave during a tantrum, you will likely reinforce that behavior and see it again in the future. So do your best to stay strong!

Neutral tone and affect.

We’re all human and it’s natural to lose our cool from time to time under stressful circumstances. Tantrums can get the best of you sometimes! In these moments, try to remind yourself to use a neutral tone and affect. Let your face and your voice send the message that you are unphased by the tantrum (even if you don’t totally feel that way on the inside!). Channel your inner actor (we’re in NYC after all!) and put on your game face!

Tune out the bystanders.

Let’s be honest, a tantrum that occurs in your home feels very different than a tantrum that occurs in public. When you are out in the community, there may be additional safety concerns (e.g. running into the street), worries about disturbing others (e.g. crying in a restaurant or movie theater), and, perhaps the most challenging of all, those darn judgmental bystanders! You know the ones we’re talking about. Those people who either can’t relate to what you and your child are going through, or the ones who pretend like they can’t relate because, after all, their children NEVER, EVER, EVER had tantrums (read: sarcasm). Then, there are also the people who get involved, thinking they’re helping you, but are actually making the situation worse. You know these people too—the sweet older lady who tells your child that Mommy will buy him a candy bar if he stops crying—you’ve met her, right? Unfortunately, you cannot always control what other people will say, do, or think. But, fortunately, you can control what YOU will say, do, and think! In these moments, do your best to turn OFF your listening ears and do what you know is right for your child.

Remember the big picture.

Okay, so here were are in the middle of a huge tantrum. Could you make that tantrum stop in a matter of minutes or even seconds? Yes, in many cases you probably could. All you have to do is give in. If your child is tantrumming because you told her you would not buy that candy bar in the checkout line, you could probably put a quick end to it by just caving and giving her the candy. And that option can be pretty tempting sometimes! This is where we urge you to remember the big picture and think long-term. The goal is not to stop that particular tantrum in that particular moment—the goal is to reduce those tantrums from happening in the long-run. We want to decrease the behavior that interferes with your child’s success and increase the behavior that supports it—that’s not going to happen by giving in. Caving in the middle of a tantrum may stop it in the moment, but ultimately it will teach your child that throwing a tantrum is an effective way to get what he wants. So the next time he wants something, he’s likely to resort to that behavior again. As you can imagine, this may easily turn into a cycle of increasing tantrums. Although it’s easier said than done, try to remember the big picture—you’ll thank yourself later!

Understand that this is a learning moment for your child.

Every moment of every day is a learning moment. This applies to all of us, by the way, not only our children! Believe it or not, your child is actually learning during those tantrums. He is learning all kinds of things, in fact! Your child is learning whether or not Mommy really means the things she says. She’s learning whether or not you are consistent. He’s learning about rules and limits, or lack thereof. She’s learning what behaviors are going to be effective and what behaviors are not. He’s learning how to respond to undesired situations, like not getting what he wants. The list could go on and on! So remember this when your child is having a tantrum and focus on teaching the things you actually WANT to teach! Furthermore, remember that learning is hard sometimes. It’s okay for your child to struggle a little bit in the learning process—you (and we!) are there to be his teachers.

Every moment of every day is a learning moment. This applies to all of us, by the way, not only our children! Believe it or not, your child is actually learning during those tantrums. He is learning all kinds of things, in fact! Your child is learning whether or not Mommy really means the things she says. She’s learning whether or not you are consistent. He’s learning about rules and limits, or lack thereof. She’s learning what behaviors are going to be effective and what behaviors are not. He’s learning how to respond to undesired situations, like not getting what he wants. The list could go on and on! So remember this when your child is having a tantrum and focus on teaching the things you actually WANT to teach! Furthermore, remember that learning is hard sometimes. It’s okay for your child to struggle a little bit in the learning process—you (and we!) are there to be his teachers.

Make objective decisions rather than emotional ones.

We’ll start this one by acknowledging that it can sometimes feel nearly impossible to be objective during a massive tantrum, especially when in public. To the best of your ability, set your emotions aside and try not to take it personally. Your child’s tantrum is happening for a reason and that reason is most likely not about trying to hurt your feelings. So, take a moment to have a mini out-of-body experience, away from your emotions, and try to look at the situation as an outsider. Remember, you want to analyze what is really happening—unfortunately, those pesky emotions can really cloud your judgment. Try to let your choices and reactions be based on facts rather than on feelings.

Stop beating yourself up!

You are not a bad parent. Your child is not a bad kid. You are not the only parent whose child has tantrums (despite those ridiculous people who make you feel like you are!) In fact, your child’s tantrum may actually be the result of you being a good parent and setting limits. You do not have to be perfect every second of every day. You can make mistakes and so can your child. It’s okay. This is a part of the process. Chin up, thumbs up, you got this!

Note: If your child engages in behavior that is dangerous to himself or others, we suggest that you consult an appropriate medical professional as well a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) immediately. Safety should always be the first priority. Feel free to reach out to our behavior team and/or attend one of our Tackling Tantrums workshops for more information on understanding and changing behavior!

WRITTEN BY BRIDGE KIDS OF NEW YORK, LLC

Bridge Kids of New York, LLC is a multidisciplinary team of professionals who strive to improve the quality of everyday living for the children and families they serve, providing each family with progressive services that merge evidence-based practices with play-based and social instruction. To find out more, contact them

here or email

info@bridgekidsny.com.

Here at BKNY, parents reach out to us for support in a variety of areas. Not surprisingly, one of the most popular reasons we hear from parents is for support in managing tantrums! Why is this not surprising? Well, it’s not surprising because very few of us will make it through life without ever throwing a tantrum! We’ve all been there, right? Whether you were 5 or 35, you’ve most likely engaged in a tantrum. For our little ones, who are still learning about rules, expectations, effective behavior, and self-control, it makes sense that we will periodically see a tantrum

Here at BKNY, parents reach out to us for support in a variety of areas. Not surprisingly, one of the most popular reasons we hear from parents is for support in managing tantrums! Why is this not surprising? Well, it’s not surprising because very few of us will make it through life without ever throwing a tantrum! We’ve all been there, right? Whether you were 5 or 35, you’ve most likely engaged in a tantrum. For our little ones, who are still learning about rules, expectations, effective behavior, and self-control, it makes sense that we will periodically see a tantrum If you cave during a tantrum, you will likely reinforce that behavior and see it again in the future. So do your best to stay strong!

If you cave during a tantrum, you will likely reinforce that behavior and see it again in the future. So do your best to stay strong! Every moment of every day is a learning moment. This applies to all of us, by the way, not only our children! Believe it or not, your child is actually learning during those tantrums. He is learning all kinds of things, in fact! Your child is learning whether or not Mommy really means the things she says. She’s learning whether or not you are consistent. He’s learning about rules and limits, or lack thereof. She’s learning what behaviors are going to be effective and what behaviors are not. He’s learning how to respond to undesired situations, like not getting what he wants. The list could go on and on! So remember this when your child is having a tantrum and focus on teaching the things you actually WANT to teach! Furthermore, remember that learning is hard sometimes. It’s okay for your child to struggle a little bit in the learning process

Every moment of every day is a learning moment. This applies to all of us, by the way, not only our children! Believe it or not, your child is actually learning during those tantrums. He is learning all kinds of things, in fact! Your child is learning whether or not Mommy really means the things she says. She’s learning whether or not you are consistent. He’s learning about rules and limits, or lack thereof. She’s learning what behaviors are going to be effective and what behaviors are not. He’s learning how to respond to undesired situations, like not getting what he wants. The list could go on and on! So remember this when your child is having a tantrum and focus on teaching the things you actually WANT to teach! Furthermore, remember that learning is hard sometimes. It’s okay for your child to struggle a little bit in the learning process Symbolic play refers to a child’s ability to use one object or action to represent a different object or action within imaginary play. The symbolic play skill that involves object substitution typically begins to emerge around 18 months. For example, you might observe a child using an empty box for a “hat” or an overturned bucket for a “drum.” Blocks are a mainstay in early childhood classrooms because the benefits are innumerable. Block play can help to facilitate cooperation, visuo-spatial skills, problem solving ability, social skills, and language development, and is a good predictor of future mathematical abilities.

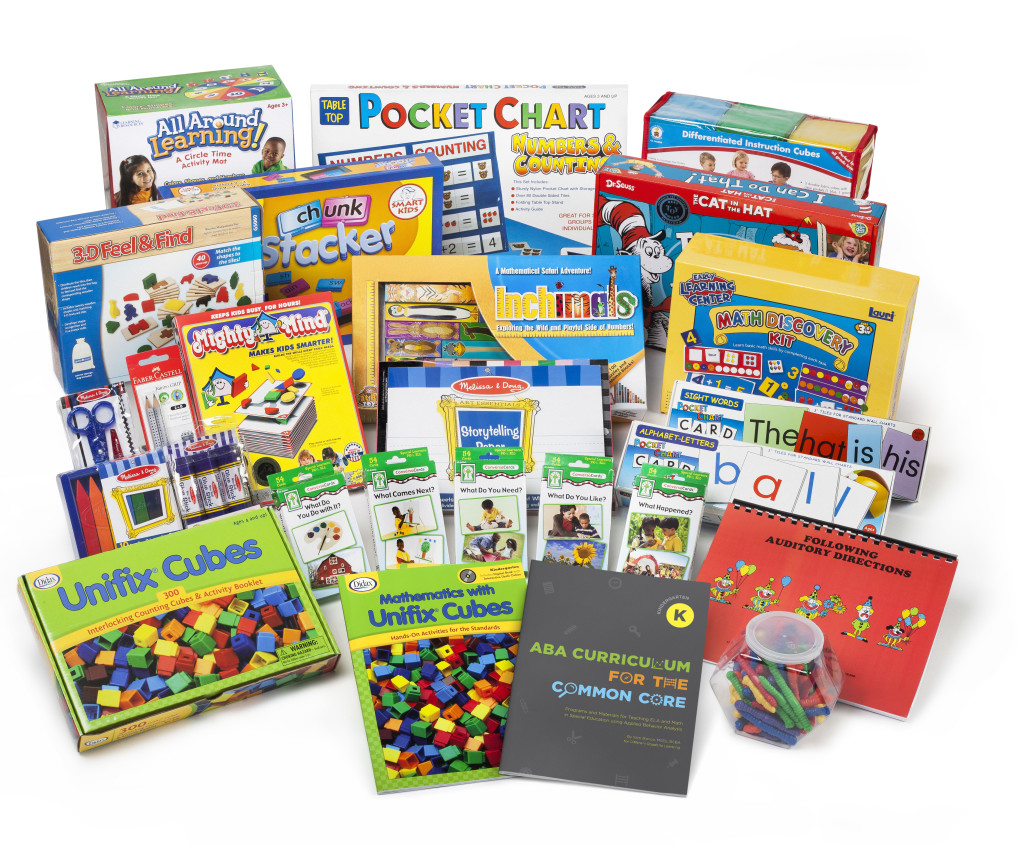

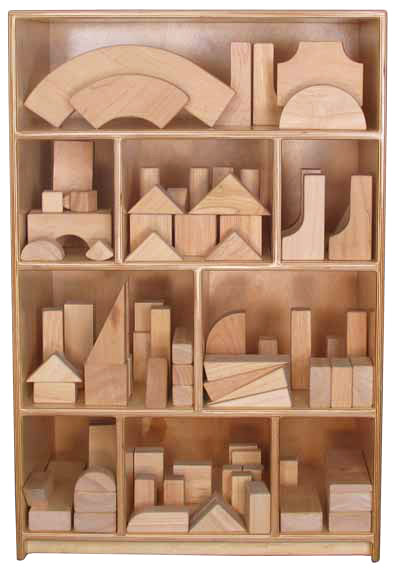

Symbolic play refers to a child’s ability to use one object or action to represent a different object or action within imaginary play. The symbolic play skill that involves object substitution typically begins to emerge around 18 months. For example, you might observe a child using an empty box for a “hat” or an overturned bucket for a “drum.” Blocks are a mainstay in early childhood classrooms because the benefits are innumerable. Block play can help to facilitate cooperation, visuo-spatial skills, problem solving ability, social skills, and language development, and is a good predictor of future mathematical abilities. One hallmark of the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder is a presence of “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends.” Additionally, rigid thinking patterns may make symbolic play difficult for children with autism as they might view objects in a limited way that makes it difficult to pretend a block is something other than a block.

One hallmark of the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder is a presence of “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends.” Additionally, rigid thinking patterns may make symbolic play difficult for children with autism as they might view objects in a limited way that makes it difficult to pretend a block is something other than a block.  Since unit blocks are a huge component of early childhood classrooms everywhere one could imagine that exposure to them and some level of proficiency opens up huge social opportunities for learners with autism spectrum disorders with their mainstream peers in the classroom.

Since unit blocks are a huge component of early childhood classrooms everywhere one could imagine that exposure to them and some level of proficiency opens up huge social opportunities for learners with autism spectrum disorders with their mainstream peers in the classroom. drawings of objects onto the blocks and then systematically fade them out. Once the learner begins to consistently use the blocks with the attached images you can use stimulus fading procedure to fade out the visual prompt. This can be done by photocopying the image and systematically changing the lightness until eventually the learner is presented with just the block.

drawings of objects onto the blocks and then systematically fade them out. Once the learner begins to consistently use the blocks with the attached images you can use stimulus fading procedure to fade out the visual prompt. This can be done by photocopying the image and systematically changing the lightness until eventually the learner is presented with just the block.

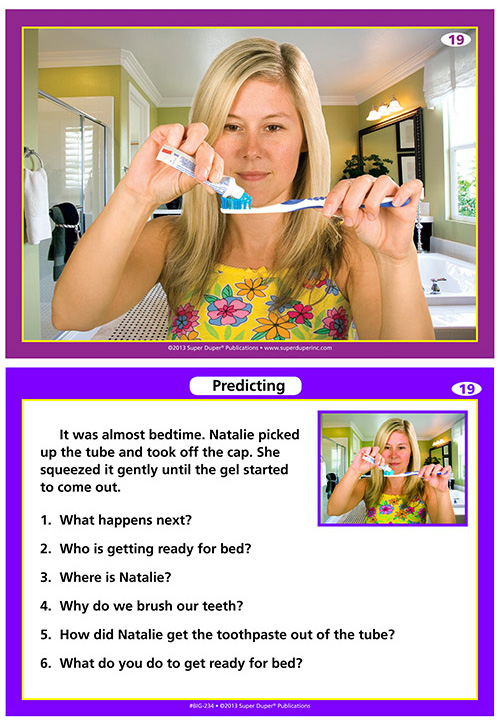

Look, Listen & Infer

Look, Listen & Infer

In this study, the researchers worked with a fifth grader with autism, a sixth grader with autism, and a fifth grader with cerebral palsy. They taught the boys to wear the MotivAider (calling it a pager) and note a + or a – to indicate their behavior each time the MotivAider vibrated. The behaviors they monitored were all related to being on-task: “eyes on my work,” “in my seat,” and “doing work.” Once each boy consistently rated his behavior upon feeling the vibration, the researchers implemented the intervention.

In this study, the researchers worked with a fifth grader with autism, a sixth grader with autism, and a fifth grader with cerebral palsy. They taught the boys to wear the MotivAider (calling it a pager) and note a + or a – to indicate their behavior each time the MotivAider vibrated. The behaviors they monitored were all related to being on-task: “eyes on my work,” “in my seat,” and “doing work.” Once each boy consistently rated his behavior upon feeling the vibration, the researchers implemented the intervention.