The iPad is a highly motivating item for many kids. But many parents and teachers find it frustrating to teach kids with autism to use the iPad functionally. Here are three tips that can help you promote functional use.

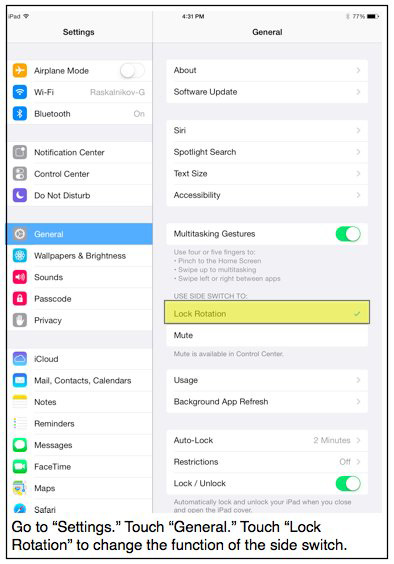

- Lock Rotation – Some learners with autism like to watch the screen rotate as they move the iPad. This prevents them from using the iPad to complete tasks, create visual or audio products, or play games. There is a small switch on the side of the iPad that is factory preset to mute the volume. You can change the function of this switch to lock rotation, preventing your learner from fixating on rotating the screen.

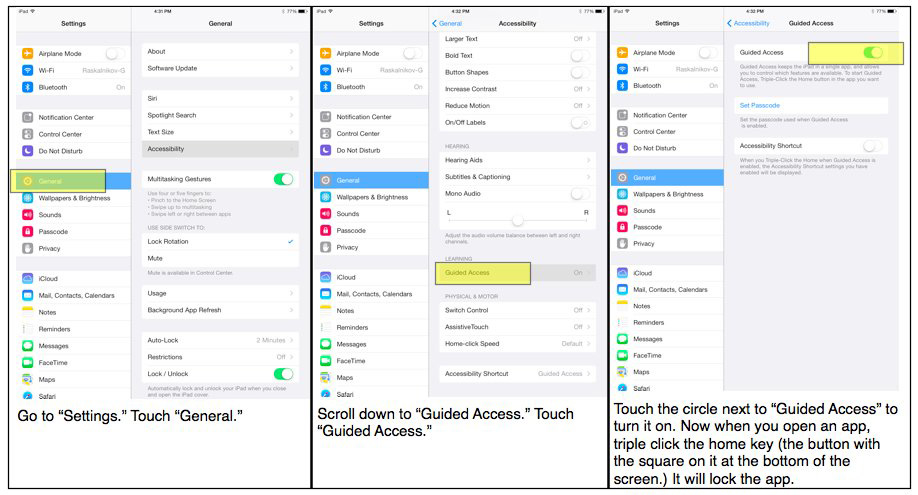

- Guided Access – When providing access to the iPad, it’s a good idea to give your learner options of particular apps to engage with instead of providing free access to everything available on the device. For example, during a teaching session, I might say, “When it’s time for a break, do you want to play Match or Simon?” When it’s time for the break, I open the app the learner chose, then activate Guided Access, which makes it impossible for the learner to switch to other apps.

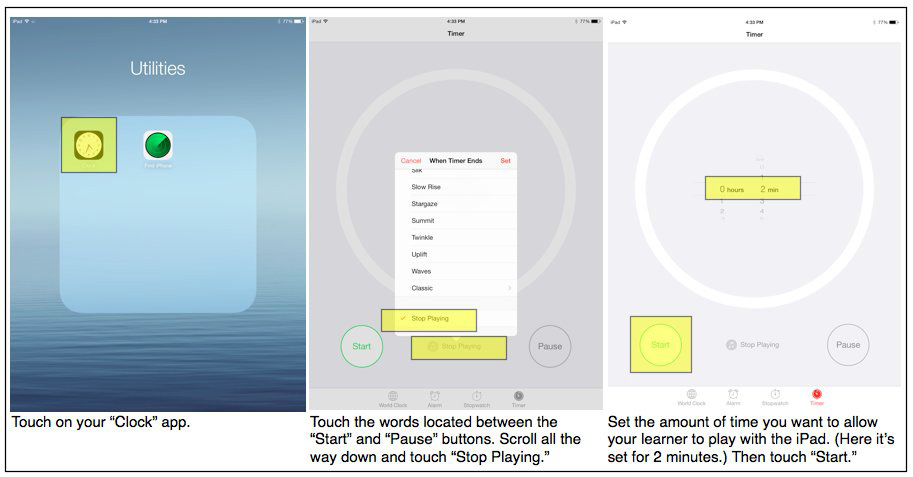

- Timed Play – Sometimes I want to limit the amount of time a learner spends on the iPad. When I am providing a student a break during a teaching session, frequently I limit the time to 2–3 minutes. Parents may allow their child to play on the iPad for 30 minutes. You can set the iPad to immediately shut off at the specified time. I like to use this function because it prevents the end of an preferred activity from being associated with me.

**Unfortunately, the iPad is the only tablet with which I am familiar. If you use another tablet and have tips such as those above, please share them with us!

WRITTEN BY SAM BLANCO, MSED, BCBA

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-12 in NYC. Working in education for ten years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam has developed strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently pursuing her PhD in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College.

Do you know of any upcoming conference or workshops on Autism?! Please let us know of any ABA, Verbal Behavior or Speech-Language Therapy events and we will share it with our community. We strive to help our readers be informed about resources and events for parents and educators of children with autism or other developmental delays. No matter how big or how small – email info about your event to

Do you know of any upcoming conference or workshops on Autism?! Please let us know of any ABA, Verbal Behavior or Speech-Language Therapy events and we will share it with our community. We strive to help our readers be informed about resources and events for parents and educators of children with autism or other developmental delays. No matter how big or how small – email info about your event to  Many students with autism and other developmental disabilities have an IEP that mandates a 1:1 paraprofessional (called an instructional assistant or teaching assistant in some states, but referred to as paraprofessional for the purposes of this article). Recently, I had the opportunity to provide a workshop to a large group of paraprofessionals in New York City. I was surprised to hear how some felt disconnected from the families of their students, especially considering how deep their relationships are with their students.

Many students with autism and other developmental disabilities have an IEP that mandates a 1:1 paraprofessional (called an instructional assistant or teaching assistant in some states, but referred to as paraprofessional for the purposes of this article). Recently, I had the opportunity to provide a workshop to a large group of paraprofessionals in New York City. I was surprised to hear how some felt disconnected from the families of their students, especially considering how deep their relationships are with their students.

We’ve always believed in the importance of nurturing independence in our students. When we came across this

We’ve always believed in the importance of nurturing independence in our students. When we came across this  The first thing I noticed when I walked in to observe was that she did her entire session at a long wooden table, sitting side-by-side with her student. After watching for about ten minutes, I asked if we could change the seating arrangement. We moved her student to the end of the table, then had the therapist sit next to her, but on the perpendicular side. This way, eye contact was much easier as they were able to face each other. The student’s eye contact improved instantly with a small environmental change. (Of course, once we made the environmental change, we worked together to address other changes that could be made to encourage eye contact.)

The first thing I noticed when I walked in to observe was that she did her entire session at a long wooden table, sitting side-by-side with her student. After watching for about ten minutes, I asked if we could change the seating arrangement. We moved her student to the end of the table, then had the therapist sit next to her, but on the perpendicular side. This way, eye contact was much easier as they were able to face each other. The student’s eye contact improved instantly with a small environmental change. (Of course, once we made the environmental change, we worked together to address other changes that could be made to encourage eye contact.)

One quote from the paper states, “Not only do people strive for freedom in a broad sense they also enjoy making simple choices, such as whether to engage in unproductive, though harmless, activities, like watching sitcoms on television, eating too many doughnuts, taking time off from work, or taking a nap before dinner.” In an effort to teach our learners independent skills, we often neglect to teach meaningful decision-making that reflects the types of decisions neurotypical adults make every day. Since the paper was originally published, there has been more work done on promoting decision-making skills for learners with developmental disabilities, but the issues described in the paper are still relevant today.

One quote from the paper states, “Not only do people strive for freedom in a broad sense they also enjoy making simple choices, such as whether to engage in unproductive, though harmless, activities, like watching sitcoms on television, eating too many doughnuts, taking time off from work, or taking a nap before dinner.” In an effort to teach our learners independent skills, we often neglect to teach meaningful decision-making that reflects the types of decisions neurotypical adults make every day. Since the paper was originally published, there has been more work done on promoting decision-making skills for learners with developmental disabilities, but the issues described in the paper are still relevant today.