The Discriminative Stimulus is defined as a stimulus in the presence of which a particular response will be reinforced (Malott, 2007, Principles of Behavior).

SD is just ABA speak for the demand, instruction, or the event/stimulus that serves as a signal to someone that there is something they need to respond to. Now, that response can also include a non-response. Not responding is always a possible choice, that comes with its own possible consequences.

For example, if my cell phone rings and it is someone I do not want to talk to I have choices:

-answer the phone

-don’t answer the phone

The phone ringing is a SD because when it rings, there is a specific response that in the past has led me to contact different consequences. Some pleasant, and some not so pleasant.

When my cell phone rings, I am not confused about what I should do. I know what my choices are, and depending on who is calling (or if I recognize who is calling) I then make a choice based on my history of reinforcement with that person.

SD’s can vary in how they are delivered, the specific reinforcement that they make available, as well as the specific expected response.

In ABA therapy sessions, sometimes hundreds of SD’s can be delivered throughout the session, and each one of those SD’s has a specific expected response, as well as specific consequences available for each possible response.

The SD has an authority based on the history of consequences being delivered.

I’ll say that another way: Let’s say I state the SD “give me blue” to a child, and I then provide a consequence of playing on an iPad if the child gives me yellow. Assuming playing on the iPad is a reinforcer, over time I am going to see the child consistently respond to my SD by giving me yellow. Is yellow in this example actually correct? No. But it does not matter: I gave my SD, I followed the child’s response with a reinforcer, and I have super-glued this particular response to the SD.

And this explains why your kids don’t listen.

Reinforcement is like the most powerful superglue on the market. It binds things together, as can be seen in the example below:

(SD) “Clean up the toys” —-> (Response) child cleans up the toys —> (Consequence) “Thanks so much, you can go outside now”

Assuming in the above example that going outside is a reinforcer, over time the child will learn the expected response to the SD of “clean up the toys”, AND they will learn that good things happen after they demonstrate the expected response. In other words, you just taught your child that when they clean up their toys, they might get to go outside.

If I flip this scenario on its head, I can show you how SD’s (and their absolute authority) can sometimes cause you to teach things you did not mean to teach:

(SD) “Clean up your toys” —> (Response) child cries/child screams “no!”/child does not respond to the SD —> (Consequence) “Ugh! Fine, I’ll clean the toys up. Just go outside while I clean up this mess”

Assuming in the above example that going outside is a reinforcer, over time what will the child learn? A few things actually:

-child will learn that problem behavior or not responding is a response

-child will learn that escape/avoidance behaviors work

-child will learn that cleaning up the toys is not a requirement to be able to go outside

Did you mean to teach that? I am nearly positive you did not. Unfortunately, the absolute authority of the SD remains unmoved by the fact that you didn’t intend to teach new ways to avoid a demand.

Don’t freak out, there is a way to avoid this trap.

First, understand what Instructional Control is and how it can help you. I promise, it isn’t as scary as it sounds.

Second, see below for some common characteristics of successful SD’s. A successful SD helps your child learn in an effective manner WHAT to do, and WHY to do it (because good things might happen). Let the absolute authority of the SD work for you, and not against you.

Characteristics of Successful SD’s

The SD is precise: A precise SD includes only the language necessary for the individual to know what to do. Extra details, threats, or reminders are best left off the SD, particularly if the individual has communication deficits or is very young. Good example – “Get down”. Not-so-good-example – “Michael Benjamin Clark, you get down off that railing right now before you fall and break your neck”.

The SD is stated, not asked: Unless you are cool with the individual tossing you a “No/I don’t feel like it/I don’t want to”, then do not present the SD as a question. A question gives the option of refusal.

The SD allows for a brief time to begin to respond: Brief as in, a few seconds. I have been in this field a long time, and I have developed an internal countdown timer that kicks in when I give a SD. To help yourself learn this skill, when you give your child a demand silently count to 3. Or, you could subtly tap a finger against the inside of your palm 3 times. If you get to 3 and the individual has not at least started to respond, it is time to provide a consequence. Another completely personal reason why I like this “internal countdown” is because it helps parents not flood the child with SD’s. If you are busy counting in your head, you can’t rattle off 4 more demands, when the child hasn’t even responded to demand #1.

The SD is consistent: Especially if the child has communication deficits or is very young, avoid changing up the SD rapidly. This can possibly be confusing, and impede learning. Once your child is demonstrating they know how to respond to the SD, that is the point where you can start to change the language used, or not use language at all (such as pointing at a book on the floor to indicate the child needs to put the book away).

The SD consequence is consistent: The most critical point about understanding SD’s is that what follows the response equals learning. You are teaching your child how to respond to you based on what happens when they respond correctly, and what happens when they respond incorrectly. If you decide that the SD “Make your bed” means fluffing all the pillows, then the bed being made with 1 pillow fluffed, or the bed being made with some of the pillows fluffed, are both incorrect responses. No exceptions. You would then prompt the correct response so the child knows they made an error.

Attention is gained before the SD is given: If you observe the ABA team work with your child you will get to see possibly hundreds of SD’s delivered during a therapy session. You may also note that the team works to gain the child’s attention before stating the SD, to make sure it is heard. This could look like approaching the child, bending/squatting down to look in the child’s face, waiting for a break in crying/screaming, or making a statement such as “Are you ready?”, to verify the child is attending.

The SD is not repeated over and over again, nor is it screamed, or shouted: SD’s are bosses. SD’s are in charge. SD’s call the shots. They do not need to beg, bargain, plead, scream, or lose their cool. Remember, your child only has a short time to respond correctly. If they do not respond correctly, you just deliver a consequence (such as a prompt). It will be very tempting to state the SD over and over again, but don’t give in to that temptation. Over time, this will actually teach your child they do not need to listen to you the first time, and that ignoring you is an effective way to avoid a demand.

About The Author

“I’ve been providing ABA therapy services to young children with Autism since early 2003. My career in ABA began when I stumbled upon a flyer on my college campus for what I assumed was a babysitting job. The job turned out to be an entry level ABA therapy position working with an adorable little boy with Autism. This would prove to be the unplanned beginning of a passionate career for me.

From those early days in the field, I am now an author, blogger, Consultant/Supervisor, and I regularly lead intensive training sessions for ABA staff and parents. If you are interested in my consultation services, or just have questions about the blog: contact me here.”

This piece originally appeared at www.iloveaba.com.

Check out this

Check out this

You can download the free printable by clicking

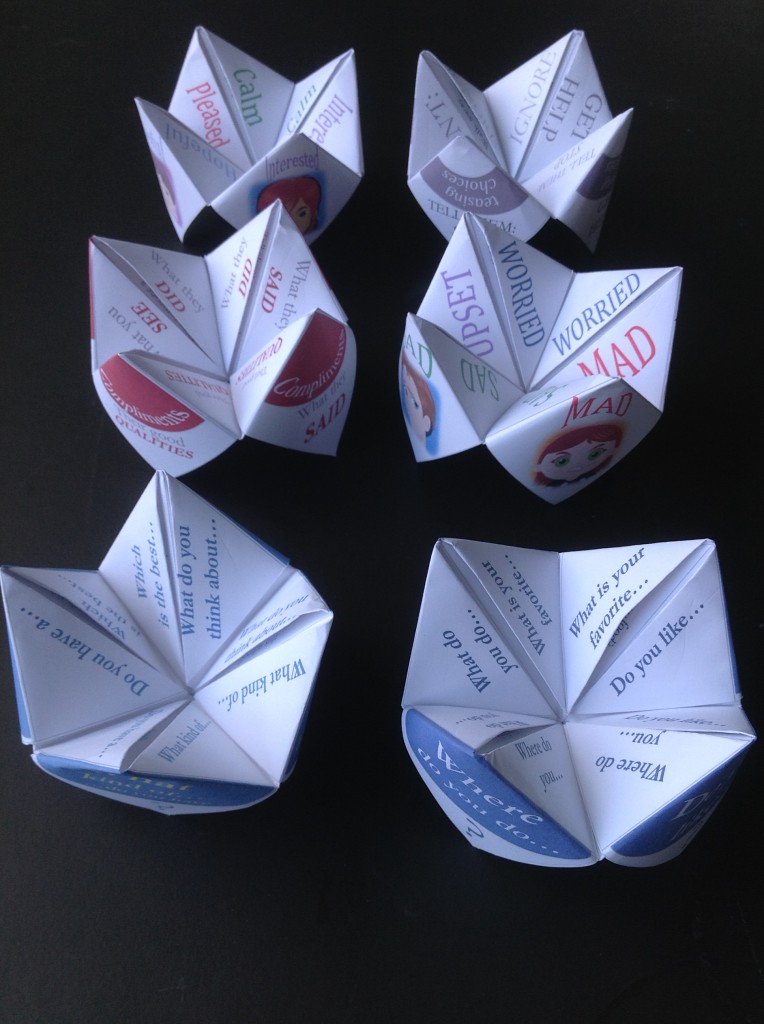

You can download the free printable by clicking  While these fortune tellers may not be able to tell your future, they are sure to help your children with autism develop their social skills! This free printable, created by Joel Shaul from

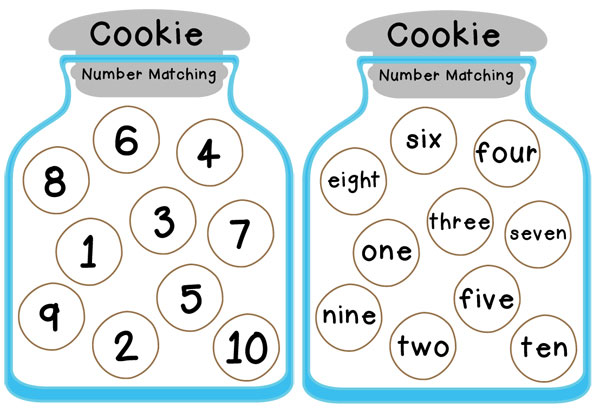

While these fortune tellers may not be able to tell your future, they are sure to help your children with autism develop their social skills! This free printable, created by Joel Shaul from  Get creative with this free number sorting activity designed by Lavinia Pop from

Get creative with this free number sorting activity designed by Lavinia Pop from  We recommend printing the activity on cardstock or laminating the crayons and pockets for longer use.

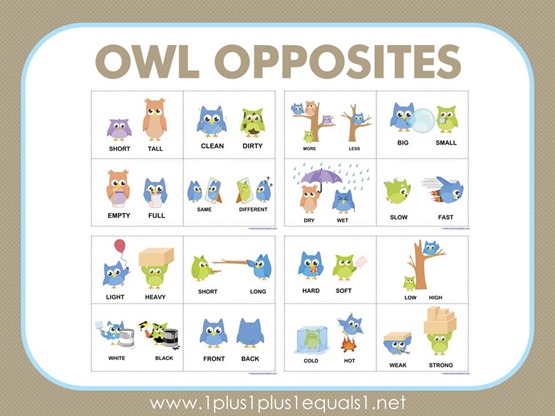

We recommend printing the activity on cardstock or laminating the crayons and pockets for longer use. The entire set features an adorable pair of owl friends who demonstrate the following sixteen different opposites:

The entire set features an adorable pair of owl friends who demonstrate the following sixteen different opposites: