“She won’t say hi unless I say ‘Say Hello.’” “He will only wash his hands if I put his hand on the knob to turn on the water.” “He won’t use his fork until I put it in his hand.”

I hear statements like this all the time from both parents and providers working with learners what autism. What they are describing is “prompt dependence,” which is when a learner requires a prompt from a teacher or parent in order to complete a task. So how do you avoid prompt dependence with your own learners?

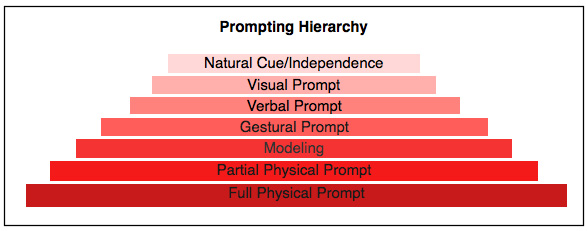

Let’s start with the prompt itself. There are many different ways to prompt which can be divided into levels by how intrusive the prompt is. Below is a sample of a prompt hierarchy, with the least intrusive prompt at the top and the most intrusive prompt at the bottom. Your goal is to quickly move through the prompt levels to move your learner to independence.

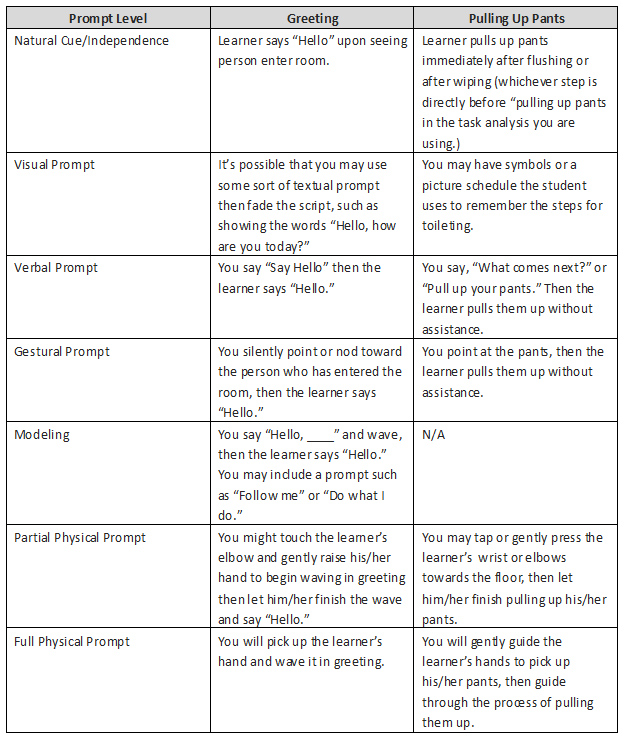

Now let’s look at two different examples to show these prompt levels. In the first example, the goal is for the learner to greet a person who walks into the room. In the second example, the goal is for the learner to pull up his/her pants after using the bathroom as a part of a toileting routine.

Research shows that least-to-most prompting increases potential for errors and slows down rate of acquisition for new skills. Therefore, most-to-least prompting is preferred for teaching new skills. This means that you would start at a full physical prompt and then move your way up the prompt hierarchy until your learner achieves independence with the task.

In the past, when working with discrete trials, it has been common practice to have a learner master a skill at a certain prompt level, then move to a less intrusive prompt and have the learner master the skill at that prompt level, steadily moving towards independence. This can actually encourage prompt dependence because the learner remains on the same prompt level for too long.

Instead, you should try to quickly move up the prompt hierarchy in a way that makes sense for the skill you are trying to teach. Below are some tips to help you help your learners achieve independence.

- Follow the rule of three: Whether you are teaching with discrete trials or in the natural environment, once your learner has successfully responded to a demand three times consecutively, move to a less intrusive prompt.

- If you are taking data, make a notation of what prompt level you are using at each step. (And remember, that only independent responses should be counted towards the learner’s percentage of correct responses.)

- At the end of a session or group of trials, note what prompt level you were at by the end of the session. Then start at that level during the next session.

- If your learner does not respond correctly when you move to a less intrusive prompt, then move back to the most recent prompt level. Once they respond again correctly at that prompt level three times consecutively, move again to a less restrictive prompt.

- Remember that verbal prompts are very difficult to fade. Though they are less intrusive, you should avoid using them when possible.

- You can pair prompts and then fade out the more intrusive prompts. For example, with the sample of pulling up pants described above, you can pair a visual prompt with a gestural prompt by showing the symbol for pulling up pants while pointing at the pants. Over time, you stop using the symbol and just use the gestural prompt. The gestural prompt can be faded by moving your point further and further away from the pants.

- Write down what the prompt levels will look like for the specific task you are teaching. This way you will be fully prepared to quickly move your learner towards independence.

- Differentiate your reinforcement! If you move to a less intrusive prompt and the learner responds correctly, then you should immediately provide a stronger reinforcer than you did for previous responses. If a learner spontaneously responds without a prompt, you should do what I call “throwing them a party” by combining reinforcers (such as tickles and high fives) or providing a highly desirable reinforcer.

Prompting can be very difficult to do well, but following these tips should help set your learner on the path to independence.

WRITTEN BY SAM BLANCO, MSED, BCBA

Sam is an ABA provider for students ages 3-12 in NYC. Working in education for ten years with students with Autism Spectrum Disorders and other developmental delays, Sam has developed strategies for achieving a multitude of academic, behavior, and social goals. Sam is currently pursuing her PhD in Applied Behavior Analysis at Endicott College.

A major tenet of Applied Behavior Analysis is that it is evidence-based. For decades, our field has conducted research about behaviors we can observe in the environment, and worked to create positive behavior change. But keeping up with research or determining what is actually evidence-based can be quite challenging.

A major tenet of Applied Behavior Analysis is that it is evidence-based. For decades, our field has conducted research about behaviors we can observe in the environment, and worked to create positive behavior change. But keeping up with research or determining what is actually evidence-based can be quite challenging.

For example, let’s say Harold frequently won’t get up independently on weekdays before school. It’s driving his parents crazy, because they have to drag him out of bed several days a week. You may set up a DRH to increase the rate of him getting up independently. Since Harold currently gets up independently at least one time per week, you would set the goal for two times per week. (You don’t want to set the goal too high, because then Harold might not ever come into contact with reinforcement, and his behavior will likely remain unchanged.) Let Harold know that if he gets up independently two days in a row, you will make his favorite breakfast on the second day. Once Harold has met this goal a few time, increase the requirement for reinforcement. You would move from two days in a row to three days in a row in order to receive his favorite breakfast.

For example, let’s say Harold frequently won’t get up independently on weekdays before school. It’s driving his parents crazy, because they have to drag him out of bed several days a week. You may set up a DRH to increase the rate of him getting up independently. Since Harold currently gets up independently at least one time per week, you would set the goal for two times per week. (You don’t want to set the goal too high, because then Harold might not ever come into contact with reinforcement, and his behavior will likely remain unchanged.) Let Harold know that if he gets up independently two days in a row, you will make his favorite breakfast on the second day. Once Harold has met this goal a few time, increase the requirement for reinforcement. You would move from two days in a row to three days in a row in order to receive his favorite breakfast. There are a few different ways to implement DRL. You might select a target number of times the behavior can be exhibited within a full session, then deliver reinforcement to the individual if they exhibit the behavior that number of times or less within the session. For example, Gina teaches in a preschool where they have a 5-minute circle time each morning. During circle time, a boy named Luke raises his hand constantly. Gina wants to reduce the number of times he raises his hand during circle time, but she does not want to eliminate the behavior altogether. She took some baseline data and discovered that he raised his hand approximately 12 times during each circle time. Gina decided that Luke would be allowed to go to the water table, (his favorite activity,) if he raised his hand 10 times or less during circle time. This is called a criterion limit. As his behavior decreased, she would decrease the number of times he was able to raise his hand in order to access reinforcement. Her goal was to get him down to 3 instances of raising his hand during the circle time activity. This procedure for DRL is useful in a classroom setting, because it does not require the teacher to take a lot of data or keep track of intervals, though that might be appropriate in other situations.

There are a few different ways to implement DRL. You might select a target number of times the behavior can be exhibited within a full session, then deliver reinforcement to the individual if they exhibit the behavior that number of times or less within the session. For example, Gina teaches in a preschool where they have a 5-minute circle time each morning. During circle time, a boy named Luke raises his hand constantly. Gina wants to reduce the number of times he raises his hand during circle time, but she does not want to eliminate the behavior altogether. She took some baseline data and discovered that he raised his hand approximately 12 times during each circle time. Gina decided that Luke would be allowed to go to the water table, (his favorite activity,) if he raised his hand 10 times or less during circle time. This is called a criterion limit. As his behavior decreased, she would decrease the number of times he was able to raise his hand in order to access reinforcement. Her goal was to get him down to 3 instances of raising his hand during the circle time activity. This procedure for DRL is useful in a classroom setting, because it does not require the teacher to take a lot of data or keep track of intervals, though that might be appropriate in other situations.